The national accounts released on Wednesday paint an alarming picture of a slowing economy that is staying in positive growth territory for all the wrong reasons.

GDP growth of 1.7 per cent over the past year is extremely sluggish, but that’s not the main point of interest.

The contribution of household consumption was the big question, because other sources of growth – government spending, business investment and net exports – aren’t enough to get things moving.

Headline household consumption wasn’t too bad, growing 0.5 per cent in the March quarter or 2.3 per cent over the past 12 months.

However, it’s the kind of consumption that is worrying.

The biggest increases in household spending were in ‘electricity, gas and other fuel’ (up 2.9 per cent) and ‘operation of vehicles’ (1.3 per cent).

The problem with the first category is that it represents ‘price inelastic’ goods. As prices rise, we still use our gas heaters or run our cars a similar amount.

Gas and electricity prices are getting eye-watering, and average unleaded prices have gone up 8 per cent since the December quarter.

So we’re spending more money and boosting ‘growth’, while consuming roughly the same amount of energy and fuel.

As for the ‘operation of vehicles’, that is harder to quantify.

Auto-industry economist Richard Johns tells me a number of factors are at work.

While currency fluctuations are not having much of an impact on car prices, Mr Johns has noticed many Australians opting for higher price-bracket vehicles.

That takes two forms. Firstly, cars are getting better, so even basic models include features such as automatic emergency braking. For some reason, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) tends to strip out those price components when it measures car-price inflation.

As a result the ABS says car prices have fallen over the past three quarters, whereas Mr Johns’ own research shows prices paid have risen.

The second factor influencing the ‘operating of vehicles’ is that Australians who earn more of their incomes from shares and property are gradually moving into luxury marques, whereas families who rely on wages are not.

That’s not just a function of ageing, but of the inequalities being created by perverse incentives in the tax system.

Savings slide

So household consumption isn’t as rosy as Treasurer Scott Morrison implies. He said on Wednesday that “household spending continues to support the economy, while household savings remain positive.”

Well only just, Mr Treasurer. While households are spending more on gas, electricity, fuel and vehicles, they are cutting back on discretionary items – alcohol spending fell 1 per cent and clothing and footware contracted 0.7 per cent.

More worrying, though, is how all this consumption is being funded.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen noted on Wednesday, “…weak household income growth is meaning that households are dipping into their savings more and more … [that’s] is not a sustainable plan for the Australian economy.”

Mr Bowen’s right, though it’s worse than he says.

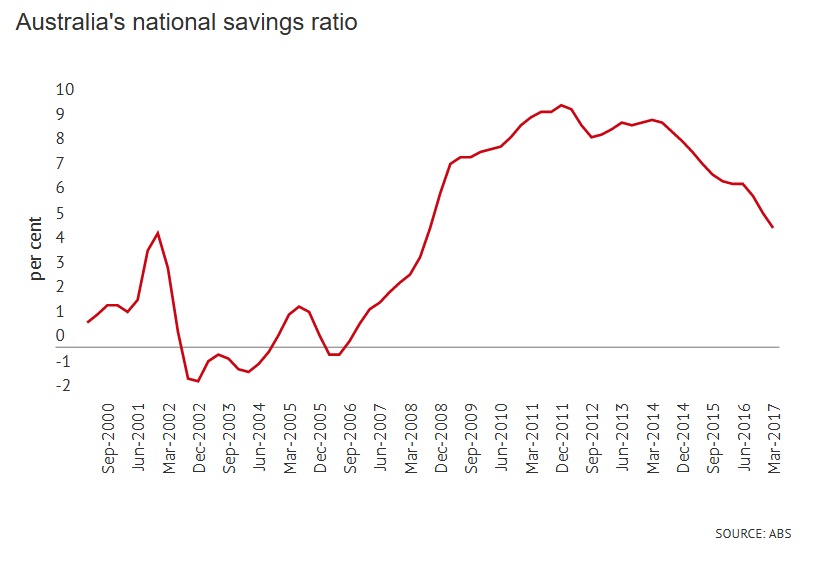

Before the global financial crisis, Australians were saving very little – often a ‘negative’ amount during 2003 to 2007 (see chart below).

What that means is that, after putting away 9 per cent of their incomes as super savings, households were not only eroding that saving by racking up debts, but sometimes borrowing more than the 9 per cent.

In the days of rapid house price growth that didn’t matter too much – the ballooning equity in homes offset the low savings rate.

But look at the figures now – we’re putting away a mandatory 9.5 per cent in super, then borrow about 4.8 per cent of our incomes to give an average savings rate of 4.7 per cent.

And this time around, house prices are forecast to remain flat or falling in the near future.

All told, the national accounts show a nation spending more on life’s essentials with less money left for the kind of spending that would buoy key areas, such as the sagging retail sector.

The economy needs stimulus, which the Treasurer obliquely admits. He said at his Wednesday media conference: “We made the right choices in the budget to invest in productivity-boosting public infrastructure and to deliver further support to small businesses to invest in their future.”

All true. These are not a good set of economic figures, but at least with those pragmatic measures in the budget the government is starting to take the problems seriously