President Donald Trump on July 10 nominated Randal Quarles to be one of the seven governors of the Federal Reserve System, the central bank of the United States.

Before I get to Quarles and his qualifications, it’s important to understand the Fed and what it does. Its decisions are vital to every person on the planet who borrows or lends money (pretty much everybody) since it has enormous influence over global interest rates. Its board of governors also influences most other aspects of the global financial system, from regulating banks to how money is wired around the world.

Quarles, for his part, is clearly qualified for a job at the pinnacle of financial regulation. He has held numerous positions in the U.S. Treasury Department, including undersecretary for domestic finance under George W. Bush, and was the U.S. executive director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He has also worked on Wall Street for The Carlyle Group and founded his own investment company, The Cynosure Group. He also has a law degree from Yale.

The issue that I believe deserves careful scrutiny, however, does not involve his qualifications. Rather it’s a view of his that, if allowed to permeate the Fed, would represent a seismic shock to how the central bank operates and could potentially have severe consequences if – or when – we stumble into another financial crisis like the one we endured only a decade ago.

Trump Fed nominee Randal Quarles, left, talks with then-central bank Chair Alan Greenspan in 2002. Reuters/Hyungwon Kang

Trump Fed nominee Randal Quarles, left, talks with then-central bank Chair Alan Greenspan in 2002. Reuters/Hyungwon Kang

How the Fed controls the world

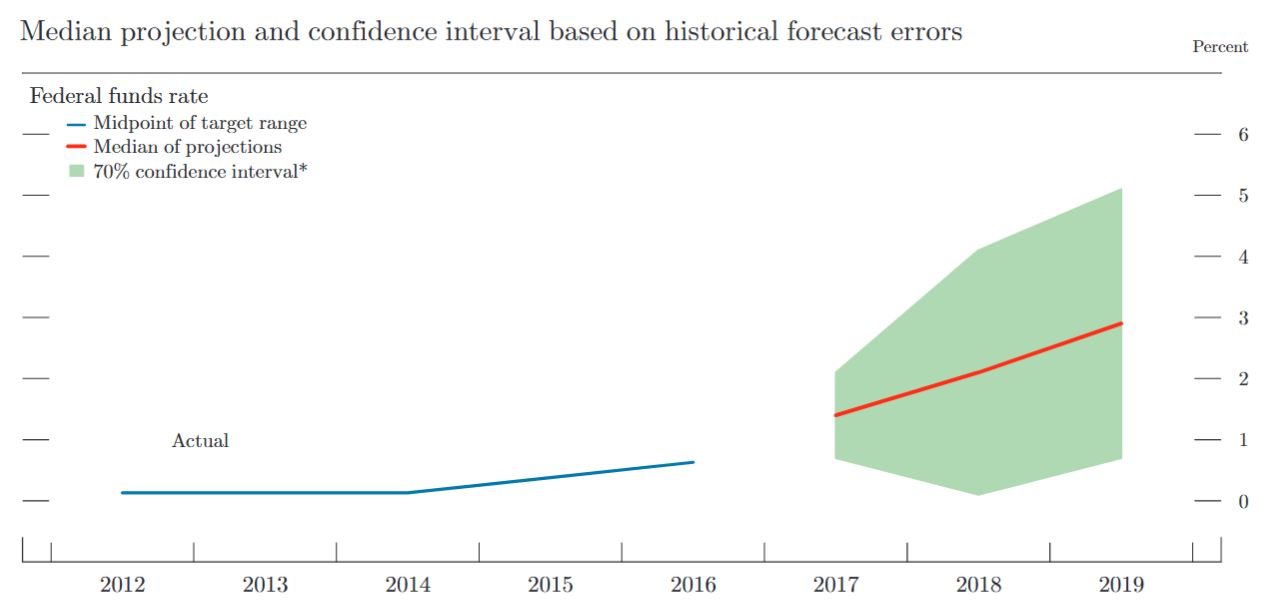

Currently, the Fed rules the financial world using a very simple model: A handful of very smart people sit together at least eight times a year and decide how to execute the country’s monetary policy.

The implications are enormous. In the words of the Fed itself, decisions made in these meetings:

“trigger a chain of events that affect other short-term interest rates, foreign exchange rates, long-term interest rates, the amount of money and credit and, ultimately, a range of economic variables, including employment, output and prices of goods and services.”

Janet Yellen currently chairs this group, called the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), and its decisions, like those of the Supreme Court, are final. There are few or no absolute rules, and there is no appeal.

Quarles, however, has described the discretionary decisions of this small group as “a crazy way to run a railroad.”

Instead, Quarles argues that the Fed should use a rules-based approach, with little or no discretion. Economic data would be plugged into a simple model, which would spit out the decision the Fed should take.

Since the model would be well-known and the relevant economic data (such as GDP, inflation rates, etc.) are already widely publicized, everyone from Wall Street to Main Street who cares about interest rates would be able to predict how the Fed is going to react under such a rules-based approach.

The Taylor rule

While Quarles has not specifically referred to which rule he would favor, a frequently cited one is called the “Taylor rule.”

It is named after Stanford economist John B. Taylor, who proposed it in 1993 as a new guiding principle for central bank decision-making. In recent years, the rule has gained much interest among people who watch and study the Fed.

The Taylor rule states that the Fed should establish short-term interest rates using a mathematical formula. It would use the current rate as a starting point and then factor in data tied to inflation and GDP, both based on the difference between the actual figures and the bank’s targets.

John Taylor created his eponymous rule to guide central bank decision-making. AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

John Taylor created his eponymous rule to guide central bank decision-making. AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

Inflation is an important variable because price changes impact people’s standard of living, while GDP growth affects the number of jobs available in the economy.

Since it would rely on a few human inputs from the Fed, the Taylor rule is somewhat flexible, enough to accommodate different situations by allowing central bankers to specify the importance of inflation compared with GDP growth.

Some countries, like Germany, primarily focus on keeping inflation extremely low. Others, such as the U.S., try to balance both inflation and GDP growth roughly equally. Central banks in some developing countries like those in Africa often put stronger emphasis on boosting economic growth with less regard to inflation.

But that’s about as far it will stretch.

Why does this matter?

In general, the Taylor rule would lead central banks to increase interest rates when inflation is high or when unemployment is very low. Conversely, the rule indicates central banks should lower interest rates when inflation is too low (or there is deflation), when economic growth is poor or unemployment is climbing.

But therein lies the rub. Rules work well when things are “normal,” but when the unexpected happens, they become much less useful – even harmful.

If the Taylor rule were an effective and straightforward method of transforming complex choices into simple, easy-to-understand decisions, the question is, why doesn’t every central bank use this rule?

The answer is as simple as the Taylor rule itself. Sometimes a country faces an economic quandary, such as what the U.S. experienced during the oil price shocks of the late 1970s. Back then, inflation was too high and GDP growth was too low, leaving the country stuck in what is known as a period of stagflation.

In these circumstances, the Taylor rule breaks down. It tells central bankers there is nothing they can do to improve economic conditions. The rule signals that interest rates need to be raised to combat high inflation, yet at the same time that would weaken already-sluggish GDP growth.

Had the U.S. followed the Taylor rule back then, it would have done nothing. Instead, the Fed raised interest rates and broke the back of inflation expectations.

What’s crazier

Simply put, central bankers around the world – including those at the Fed – have not adopted rules-based monetary policy using the Taylor rule or another because in times of economic crisis, a simple precept usually fails to provide effective solutions.

The current ad-hoc approach provides maximum flexibility and allows central bankers to reach for untested methods that help them get the economy back on track.

Quarles may be right. It might be a crazy way to run a railroad. But then again, monetary policy – and the US$18.6 trillion U.S. economy – is a bit more complex than operating a train on a set of rails. The crazy thing might be to do it any other way.