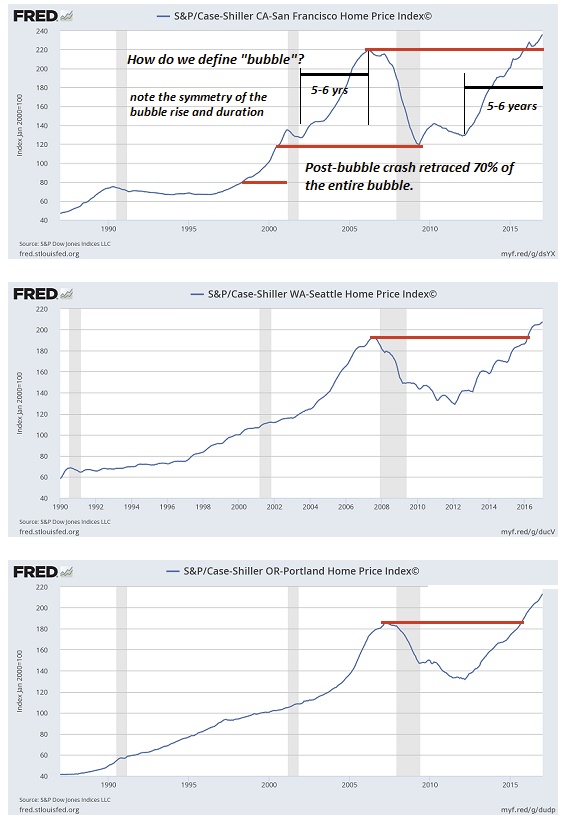

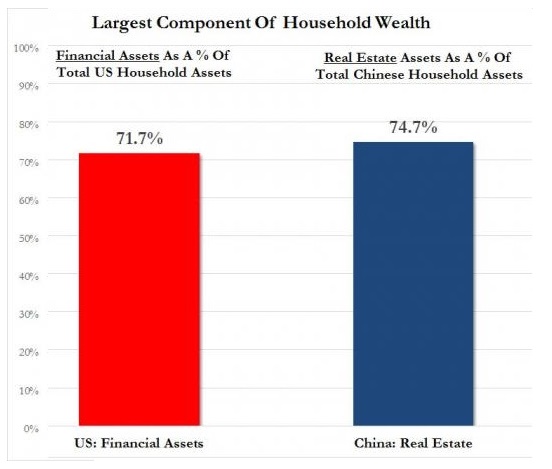

Among a host of other issues, one the critical things that contributed to the housing crisis of 2008 was the fact that speculative borrowers had nearly no “skin in the game.” Anyone who decided they wanted a piece of the rapidly inflating housing bubble could go out and buy multiple houses with no money down or, in some cases, even do “cash out” purchases whereby banks would finance more than 100% of the purchase price leaving ‘buyers’ to pocket the excess.

Shockingly, such terrible underwriting standards was a really bad idea. Turns out that offering investors infinite returns on capital, given that they could purchase millions of dollar worth of assets without ponying up a single penny, causes wild speculation resulting in devastating asset bubbles.

But, in the wake of one of the worst asset bubbles in history, new legislation came along requiring traditional mortgage borrowers to put 20% down when purchasing a new home.

Ironically, the new owner of one of the worst mortgage lenders of the 2008 era, is now arguing that down payment requirements should be slashed in half. Speaking to CNBC, Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan, the proud owner of Countrywide Financial, said that his mission is to reduce mortgage down payment requirements to 10% for traditional loans. Per CNBC:

“But, you know, I think at the end of the day is people forget that, at different points in your life and different points on what you’re doing in life requires you to think about housing differently as a place for you and your friends, as a place for you and maybe your significant other, and then ultimately, a place for family. That drives change. And so yes, it’s taken more time. And we talked a lot about this, you know, four or five years ago, that if you require a 20% down payment, it takes just a little more time to accumulate 20% than it would 3% or none, which is what the rules were for a short period of time.”“So our goal, going back to regulatory reform, is should you move the down payment requirement from 20% to 10%? Wouldn’t introduce that much risk.”

“But would actually help a lot of mortgage to get done. And if you look at the statistics, the difference between 80 and 90 LTV –loan-to-value – isn’t much different as it is between 95 and 90. That’s when you start to see real differences in performance statistics. And so we don’t want to wish people into borrowing money that then they have trouble repaying.”

Of course, we’re certain that Moynihan’s sole purpose for wanting to lower down payments is to help those poor millennials living in mom’s basement and has nothing to do with the fact that’s he’s lost a ton of fee revenue to government-backed loans that only require a 3% down payment.

But, why not? Gradually destroying lending standards worked out really well last time around.