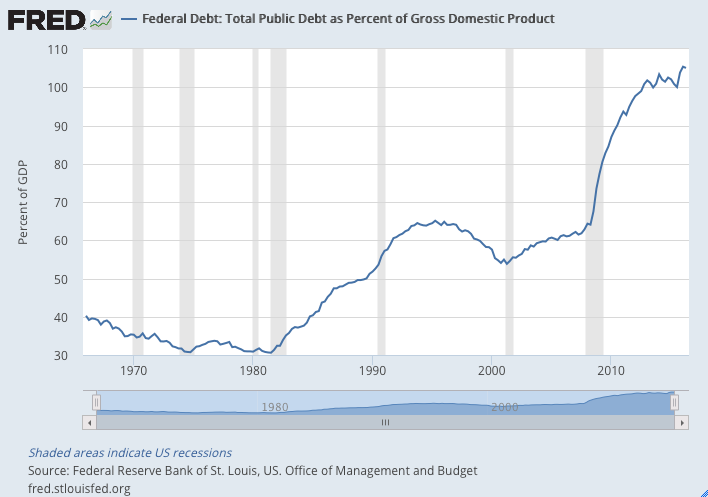

One of the things that caught my attention this morning was that the US government’s debt level has soared to just a hair under $19.7 trillion.

To give it some context, that’s up over $170 billion in just eight business days.

It’s almost as if Barack Obama is intentionally and desperately trying to breach the $20 trillion mark before he leaves office in January.

The election is merely a fight over who gets to be the band conductor while the Titanic sinks. And the debt is precisely the reason for this.

Total US public debt has skyrocketed over the last eight years by $9 trillion, from $10.6 trillion to $19.7 trillion.

And in the 2016 fiscal year that just closed two weeks ago, the government added a whopping $1.4 trillion to the debt, the third highest amount on record.

Plus, they managed to accumulate that much debt at a time when they weren’t even really doing anything.

It’s not like the government spent the last year vanquishing ISIS or rebuilding US infrastructure. They just… squandered it.

Stiglitz claims that we wouldn’t judge a private company like Apple based solely on its debt.

We’d look at other factors like assets, income, and growth before making an assessment of the company’s financial health.

And he’s right.

Singapore, for example, is a country with an extremely high level of debt. At first glance, it looks dangerous.

But if you dive deeper into the government’s balance sheet, you see an enormous abundance of cash reserves.

So taking into account just its cash assets, Singapore has absolutely ZERO net debt.

The US, on the other hand, is not in this position.

The Treasury Department publishes regular financial statements detailing its income, expenses, assets, and liabilities.

You already know the income numbers– the government loses billions of dollars per year, and the trend is negative.

As for its balance sheet, the government reports just $3.2 trillion in assets against $21.4 trillion in liabilities, for a NET position of NEGATIVE $18.2 trillion.

Now, when we’re dealing with trillions, it’s clearly not an exact science.

There are many economists who argue that the federal highway system, military, and federal tax authority should count as “assets” that are worth trillions of dollars.

Maybe so. But to be fair, one should also count the trillions of dollars of repairs needed on the highway system as liabilities.

Or the trillions more in cost of wars. Or the $40+ trillion in unfunded liabilities from Medicare, Social Security, etc.

It’s also important to note that America’s debt is growing at a far quicker rate than its economy.

When President Obama took office, US public debt was about 73% of GDP. Today it’s 105%. So even as the economy has grown, the debt has grown much faster.

Any way you look at it, the US government is already insolvent, and its situation is becoming worse.

Tag: USA

Is The Stock Market About To Turn Significantly Lower?

Stock prices have been supported by high dividends and buybacks. But this may be ending, and if so, multiples will fall, potentially leading to a correction. And this is before the Fed moves their benchmark rate.

Over the past several years, there have been two primary sources of upside for the stock market: trillions in corporate buybacks, as companies themselves engaged in record repurchases of their own stock, often at price indiscriminate levels in a bid to not only raise the stock price but also the stock-linked compensation of management , and a similar amount of dividend payments which in a time of negligible yields, became one of the main drivers for buyers to scramble into the “safety” of dividend paying stocks. Collectively these account for an unprecedented amount of payouts to shareholders.

Today, Barclays’ head of equity strategy Jonathan Glionna quantifies just how much corporate cash flow has and will be used to fund these payouts.

Glionna finds that in aggregate the companies within the S&P 500 are returning a record amount of cash to shareholders through dividends and buybacks. Since 2009 dividends have increased by more than 100%, reaching $98 billion in the most recent quarter. Meanwhile, gross buybacks have tripled and Barclays forecasts that they will reach $600 billion in 2016. In fact, buybacks plus dividends could surpass $1 trillion in 2016, for the first time ever.

Just like Goldman Sachs, Glionna says that “we believe the substantial increase in distributions is one of the primary justifications for the gains in the price of the S&P 500 during this business cycle (Figure 1).

However, this unprecedented surge in distributions may be coming to an end and as Barclays puts it, “alas, nothing continues forever. The growth rate of payouts, which has averaged 20% since 2009, will all but disappear in 2017, in our opinion.”

While companies have “taken advantage of a recovering economy and generous credit market to enhance both dividends and buybacks” for six years, they may not be able to push them higher much longer.

And here is a fascinating statistic: over the last few years payouts have exceeded earnings for the S&P 500, which is rare. It almost happened in 2014, when the total payout ratio was 99%. In 2015, it did happen. It will happen again in 2016, based on Barc estimates, as net income is likely to be less than $900 billion against $1 trillion of dividends and buybacks. Prior to 2015, companies in the S&P 500, in aggregate, had paid out more than they earned only six other times during the last 50 years. It has never happened more than two years in a row (Figure 2).

In addition, cash outflows for dividends and buybacks have been exceeding cash flow from operations after capital expenditures. We discussed this in The end of financial engineering? (February 29, 2016), which highlighted the S&P 500’s growing reliance on the investment grade credit market to cover its cash flow deficit. Based on our measure, companies in the S&P 500 have spent more than they generated in free cash flow every year since 2013.

The kicker: Glionna estimates that non-financial companies in the S&P 500 have a cash flow shortfall of more than $115 billion per year (Figure 3). In other words, companies will spend promptly send every single dollar in cash they create back to their shareholders, and then use up an additional $115 billion from cash on the balance sheet, sell equity or issue new debt, to fund the difference.

Door Still Open For Fed Rate Cut

Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer spoke at the 31st Annual Group of Thirty International Banking Seminar, Washington, D.C. on the U.S. Economy and Monetary Policy.

After running through the current numbers, he turned to the monetary policy outlook. The labor market seems to be the key.

As you know, at our September meeting, the FOMC decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 1/4 to 1/2 percent. As we noted in the statement, the recent pickup in economic growth and continued progress in the labor market have strengthened the case for an increase in the federal funds rate.3 Indeed, in our individual economic projections prepared in advance of the September meeting, nearly all FOMC participants anticipated an increase in the target range for the federal funds rate by the end of this year. Moreover, as economic growth has picked up and some of the earlier concerns about the global outlook have receded, the Committee judged the risks to the U.S. economic outlook to be roughly balanced.

Given that generally positive view of the economic outlook, one might ask, why did we not raise the federal funds rate at our September meeting? Our decision was a close call, and leaving the target range for the federal funds rate unchanged did not reflect a lack of confidence in the economy. Conditions in the labor market are strengthening, and we expect that to continue. And while inflation remains low, we expect it to rise to our 2 percent objective over time. But with labor market slack being taken up at a somewhat slower pace than in previous years, scope for some further improvement in the labor market remaining, and inflation continuing to run below our 2 percent target, we chose to wait for further evidence of continued progress toward our objectives.

As we noted in our statement, we continue to expect that the evolution of the economy will warrant some gradual increases in the federal funds rate over time to achieve and maintain our objectives. That assessment is based on our view that the neutral nominal federal funds rate–that is, the interest rate that is neither expansionary nor contractionary and keeps the economy operating on an even keel–is currently low by historical standards. With the federal funds rate modestly below the neutral rate, the current stance of monetary policy should be viewed as modestly accommodative, which is appropriate to foster further progress toward our objectives. But since monetary policy is only modestly accommodative, there appears little risk of falling behind the curve in the near future, and gradual increases in the federal funds rate will likely be sufficient to get monetary policy to a neutral stance over the next few years.

This view is consistent with the projections of appropriate monetary policy prepared by FOMC participants in connection with our September meeting. The median projection for the federal funds rate rises only gradually to 1.1 percent at the end of next year, 1.9 percent at the end of 2018, and 2.6 percent by the end of 2019. Most participants also marked down their estimate of the longer-run normal federal funds rate, with the median now at 2.9 percent.

However, as we have noted on many previous occasions, policy is not on a preset course. The economic outlook is inherently uncertain, and our assessment of the appropriate path for the federal funds rate will change in response to changes to the economic outlook and associated risks.

US Economy In The Debt Trap

We’ve been waiting for the U.S. economy to reach escape velocity for the last six years. But it may never make it, thanks to debt, according to Zero Hedge.

We’ve been waiting for the economy to finally become self-stimulating and no longer require monetary or fiscal stimulus to keep it from stalling out. Unfortunately, this may not be possible the way things are going.

In short, the U.S. economy may never reach “escape velocity” unless it is first allowed to crash. It has been too larded up and larded over with debt for any real sustainable growth to take root. More evidence, to this effect, was revealed this week.

For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) anticipates the U.S. economy will expand by just 1.6 percent this year. That’s about one percent less than last year’s estimated growth. In other words, the rate of economic growth in the United States isn’t increasing; rather, it’s decreasing.

According to the IMF, “the slower-than-expected activity comes out of the ongoing oil industry slump, depressed business investment and a persistent surplus in business inventories.” Could this be the twilight of the weakest economic recovery in the post-World War II era? Only time will tell, for sure.

But anyone with an ear to the ground and a nose to the grindstone knows the answer to that question. Business ain’t booming. Moreover, it has become near impossible for corporations to grow their earnings.

Debt Subsistence

Specifically, corporate earnings for S&P 500 companies have declined for five consecutive quarters. That’s quite a slump, indeed. What’s more, over the next several weeks, we’ll discover if third quarter earnings decline for six consecutive quarters.

We suppose if earnings decline for long enough they’ll eventually have to go back up. Still, we seem to think a bigger adjustment will occur before corporations rediscover their footing. In fact, we expect this adjustment to be accompanied by increases in layoffs, company reorganizations, and corporate bankruptcies.

US non-financial corporate debt – up and away! The problem is, when it does decline, it usually feels like the world is about to end. This is the result of the unholy trinity of fiat money, central banking and a fractionally reserved banking system.

With today’s elastic funny money, economic growth is dependent upon greater and greater issuance of debt to subsist. Still, central bankers and their cohorts at the treasury haven’t eradicated the business cycle. Episodes of economic recession invariably happen, including massive debt pileups and bankruptcies.

Where government finances are concerned, it only takes a moderate growth stall out for budgets to get blown to pieces. The money, remember, has already been allocated. So when tax receipts slide deficits explode. Then, in a seemingly counter-intuitive way, even greater issuance of debt – in the form of fiscal stimulus – is needed to keep the debt from piling up even more.

For in a twisted way, backing off on new debt issuance, and the resulting subsequent economic drop off, actually causes debt ratios to increase. This, of course, is the Keynesian argument against austerity.

Doomed to Failure

We don’t like it. We don’t agree with it. We’d prefer an honest and stable money supply, and the impartial discipline it exacts on an economy. But unfortunately, the world as it presently exists, is based on a system of dishonest money that robs savers and rewards borrowers.

Obviously, such a devious system is doomed to failure. Once the economy has become so dependent upon stimulus to persist, new stimulus fails to prop up further growth. Like the Ouroboros, the mythical serpent eating its own tail, eventually it consumes itself.

From a pure financial standpoint, the United States is going to hell in a hand bucket. The national debt is clocked at $19.5 trillion. But GDP is just $16.5 trillion.

US public debt to GDP ratio; it currently stands at about 105%. Why not higher? The calculation is based on nominal GDP, since the debt is reckoned in nominal terms as well. Still, this is the above the level that has historically been associated with economic stagnation (and eventually, worse).

As noted above, per the IMF, estimated growth for 2016 is 1.6 percent. Yet the estimated budget deficit is 3.3 percent of GDP . In short, debt is increasing. Growth is stagnating.

US Consumer Credit Stronger

The latest consumer credit data from the federal reserve, including provisional data for August 2016 shows rise to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 8-1/2 percent. Revolving credit increased at an annual rate of 7 percent, while nonrevolving credit increased at an annual rate of 9 percent.

The data set covers most credit extended to individuals, excluding loans secured by real estate. The percent changes are adjusted to exclude the effect of such breaks. In addition, percent changes are at a simple annual rate and are calculated from unrounded data.

The data set covers most credit extended to individuals, excluding loans secured by real estate. The percent changes are adjusted to exclude the effect of such breaks. In addition, percent changes are at a simple annual rate and are calculated from unrounded data.

Nonrevolving includes motor vehicle loans and all other loans not included in revolving credit, such as loans for mobile homes, education, boats, trailers, or vacations. These loans may be secured or unsecured.

Here is the longer term trend. Shaded area is the great recession. We see similar growth rates over the past couple of years, highlighting credit growth higher than inflation or income. Further evidence of the growing household debt.

The U.S. economy is in desperate need of a strong dose of fiscal penicillin

Despite six years of “recovery” from the Great Recession, America’s middle class still struggles financially amid sluggish economic growth and middling job creation.

The Federal Reserve’s near-zero interest rates have helped stabilize the economy after it nearly went into freefall in 2008 and 2009, but that policy is coming to an end, with at least one quarter-point hike expected this year and more in 2017 and 2018.

So what will support the economy once the Fed’s largesse begins to disappear?

I’ve been exploring the key economic data – from productivity and housing to wage growth and consumer spending – to better understand where we’re headed and what is needed to get out of this no-to-low growth environment, a pernicious state some economists call secular stagnation. The data show clearly why serious attention is needed to foster faster growth, a more competitive economy and more opportunities for American families.

And only one institution, I would argue, is able to do something about it: Congress.

Stagnant growth and productivity

For most of the recovery, economic growth has been lackluster.

Gross domestic product has expanded at an average annual inflation-adjusted rate of just 2 percent since the recession ended in the second quarter of 2009, far below the rate of 3.4 percent from December 1948, when the first recession after World War II started, to December 2007, when the most recent recession began. And in just the past three quarters through June, the economy has barely budged, growing at an anemic 1 percent or so.

Productivity growth, measured as the increase in inflation-adjusted output per hour, is key to propelling strong economic growth because it means that workers are getting better at doing more in the same amount of time. Yet productivity rose only a total of 6.6 percent from the second quarter of 2009 to the second quarter of 2016. That amounts to an average rate of 0.9 percent a year, a fraction of the 2.3 percent we experienced from 1948 to 2007.

Housing hasn’t recovered

When considering what’s keeping the recovery from taking off, housing deserves particular attention since it generally boosts economic growth after a recession. Not this time.

Sales of new single-family homes have been on the rise in recent years, but they’re still well below the historical average before the Great Recession, pushing homeownership down to a 50-year low. Sales averaged about 400,000 a year from 2011 to 2015, compared with 698,000 before the recession – from 1963 through 2007.

Although the pace has picked up in recent months – reaching an annual rate of 609,000 in August – it’s still not enough to stop the slide in the homeownership rate, which was 62.9 percent in the second quarter, down from 67.8 percent at the end of 2007.

And spending on housing fell 7.7 percent in the second quarter of 2016, compared with the first three months of the year.

One of the reasons housing has been slow to recover – the market’s collapse was the primary cause of the Great Recession – is that employment growth has remained mostly moderate. Many are still looking for good jobs despite the sharp drop in headline unemployment to an eight-year low of 4.9 percent.

The average annualized employment growth rate from June 2009 to August 2016 was just 1.4 percent, well below the long-run average of 1.9 percent from December 1948 to December 2007.

While there were 13.6 million more jobs in August than in June 2009 – meaning that the economy regained all those lost during and immediately after the recession – these gains and the comparatively low unemployment rate obscure that many people still cannot find the jobs they want. The jobless rate means about 7.8 million individuals were unemployed in August, yet another 7.8 million were either employed part time for economic reasons (they would have preferred a full-time job) or out of work and wanted a job but weren’t counted in the official rate because they hand’t looked in the preceding four weeks.

And communities of color still have higher unemployment rates than whites. The African-American unemployment rate stood at 8.1 percent, while for Hispanics it was 5.6 percent, compared with 4.4 percent for whites.

Wage growth, income inequality and debt

These lackluster job gains have meant there’s less pressure on employers to raise wages. And sluggish wage growth has meant less consumer spending – which typically makes up more than two-thirds of GDP.

Wages, in fact, have barely kept pace with price increases. Inflation-adjusted hourly earnings of production and non-supervisory workers – about 80 percent of the labor force – have increased only about 4.5 percent since June 2009. This amounts to an annualized growth rate of merely 0.6 percent above the rate of inflation over the past seven years.

Low wage growth has kept income inequality at very high levels. A recent report offered some good news: Real median household income grew at 5.2 percent, from US$53,718 in 2014 to $56,516 in 2015 – the fastest annual growth on record dating back to 1968. But inflation-adjusted median income was still higher in 2007 than in 2015.

Middle-class Americans are only slowly gaining ground as wealthier ones had seen bigger gains, leaving income inequality persistently high. In 2015, the top 5 percent of earners captured 22.1 percent of total income, compared with 11.3 percent for the bottom 40 percent. In 1967, those at the top took home 17.2 percent, versus 14.8 percent for the bottom 40 percent.

This lack of wage growth also makes it difficult for households to dig out from under a mountain of debt, which further contributes to limited spending on housing and other items. Household debt equaled 105.2 percent of after-tax income in the second quarter of 2016. While that’s down from a peak of 135 percent in the fourth quarter of 2007, the current level is still much higher than any level of debt observed in the 50 years before 2002.

Moreover, some especially costly forms of credit have grown. Installment debts – mainly student and car loans – have grown from 14.6 percent of after-tax income in June 2009 to 19.2 percent this past June – the highest share since records began in 1968.

Unsurprisingly, consumer spending growth has been middling as a result, increasing an average of just 2.3 percent a year since the end of the Great Recession, far below the long-term average of 3.5 percent from 1948 through 2007.

Companies on the sidelines

With their consumers still mired in debt with little gain in their pocketbooks, businesses have very few reasons to invest.

Net investment – what companies spend on new capital assets rather than on replacing obsolete items – has averaged 1.9 percent of GDP since the recession started at the end of 2007. This is the lowest since World War II.

To be clear, companies have the money. Corporate profits recovered quickly toward the end of the Great Recession and have stayed high since.

So where is all that money going? Cash reserves and shareholders.

Nonfinancial corporations hold an average of 5.2 percent of all of their assets in cash – a high rate by historical standards. At the same time, they spent on average 99 percent of their after-tax profits on dividend payouts and share repurchases to keep their shareholders happy since the start of the Great Recession.

Breathing room

With consumers not spending money because they can’t and businesses not spending money because they don’t want to, the onus falls on Congress to bolster the economy and the labor market.

Yet federal, state and local government spending has been falling. Their total spending on goods and services as a share of GDP was 17.7 percent in the second quarter of 2016, the smallest share since 1998.

Congress, though, now has room to maneuver. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated in August that the federal government will have a deficit of 3.2 percent of GDP for fiscal year 2016. This is much smaller than in recent years, including 2009’s deficit of 9.8 percent of GDP – the widest since World War II.

The shrinking deficit, as well as the government’s near-record-low borrowing costs, could provide enough breathing room to focus on targeted, efficient policies that promote long-term economic growth and shared prosperity, for instance, through investments in infrastructure.

The economy and American families need Congress to use this breathing room to create real economic security.

Author: Christian Weller, Professor of Public Policy and Public Affairs, University of Massachusetts Boston

Another Revenue Challenge

According to Moody’s the new Focus on US Banks’ Sales Practices Is Another Revenue Challenge.

Last Tuesday, Thomas Curry, head of the US Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), indicated during testimony before the US Senate Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs Committee that his agency will conduct a horizontal review of sales practices at the nation’s largest banks. Later, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) Director Richard Cordray added that his agency would be “doing a joint action” with the OCC.

We believe regulators will conduct a particularly thorough review of the industry’s sales practices in response to the media and political spotlights on Wells Fargo & Company’s (A2 stable) recently disclosed wrongdoings, the unauthorized opening of up to 2.1 million deposit or credit card accounts. For the banks, the additional regulatory focus is credit negative because it will increase scrutiny on deposit fees, which are a meaningful contributor to their revenue.

Deficient sales practices have only been highlighted at Wells Fargo and nowhere else. Nonetheless, in underscoring the need for a broader review, Mr. Curry highlighted the importance of incremental product sales and fees, noting that protracted low interest rates put the industry, not just Wells Fargo, “under enormous margin pressure.”

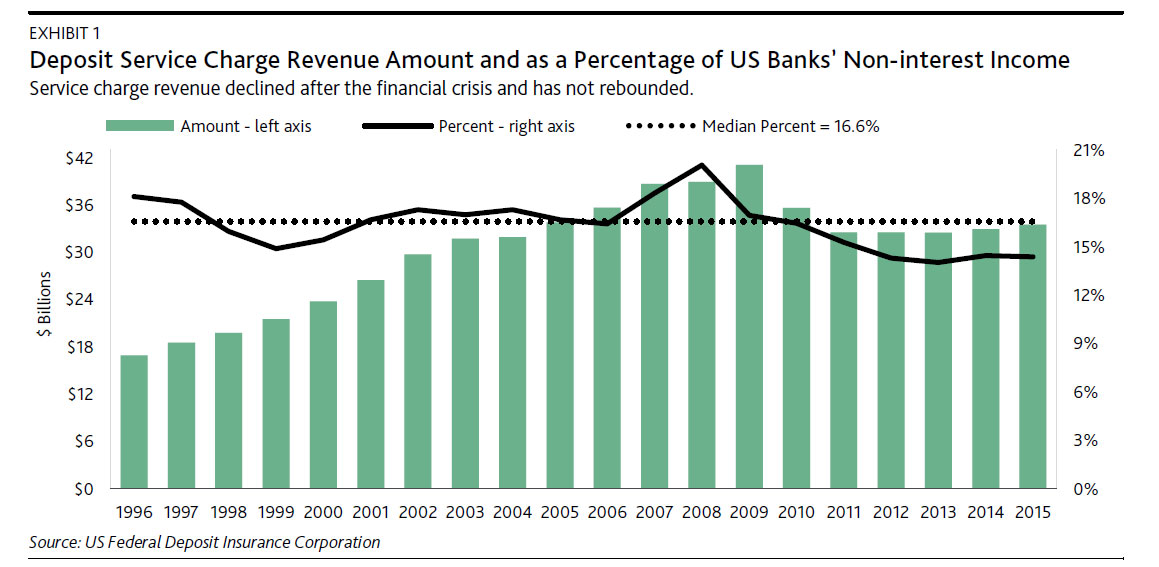

As shown in Exhibit 1, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) data show that service charges on deposit accounts are significant for the industry, totaling nearly $34 billion in 2015, or 14% of total noninterest revenue. Large as this number is, it has fallen in absolute terms and as a percentage of non-interest income since the 2008-09 financial crisis, primarily because of heightened regulation. The additional exams announced last week will only reinforce existing scrutiny over specific revenue sources, such as overdraft fees.

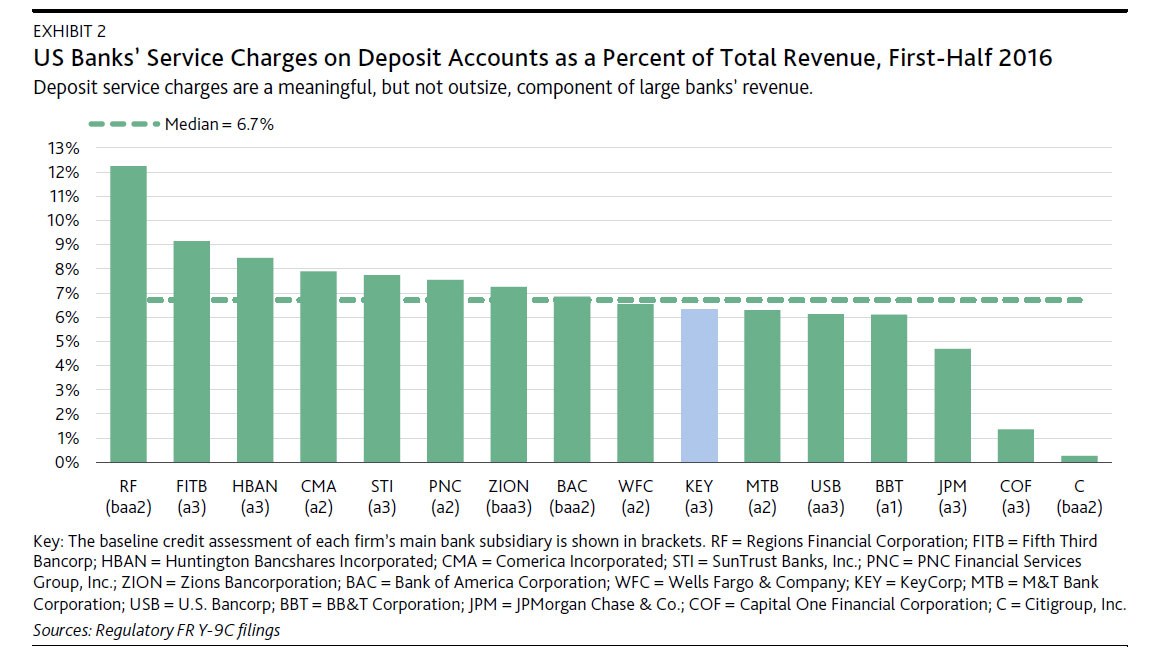

The misconduct at Wells Fargo has put all large banks in the regulators’ crosshairs. Exhibit 2 shows that for most large banks, deposit service charges are a meaningful contributor to overall revenue; that is, the combination of net-interest income and non-interest income. Specifically, for the first six months of 2016, 16 large banks reported a median contribution to total revenue of 6.7% from service charges on domestic deposit accounts, with one bank in the group, Regions Financial Corporation (Baa3 review for upgrade), earning 12% of its total revenue from this source.

Although some senators at last week’s hearing highlighted their worry that inappropriate sales practices could be widespread, that determination has not yet been made. Regardless, we believe the revelations at Wells Fargo will cause banks to tread cautiously before rolling out more aggressive sales initiatives in the current environment. That alone will constrain their revenue growth

US Household Net Worth Rises

The latest (Q2 16) US Financial Accounts have been released, containing data on the flow of funds and levels of financial assets and liabilities. The data will increase the likelihood of a fed rate rise, offsetting the more negative news released yesterday.

The net worth of households and nonprofits rose to $89.1 trillion during the second quarter of 2016. The value of directly and indirectly held corporate equities increased $452 billion and the value of real estate rose $474 billion. The figure plots the contributions to the change in net worth of households and nonprofit organizations. The black line plots the total change in net worth, while the bars represent the changes in the main components of net worth: market value of directly and indirectly held corporate equity (dark blue), market value of real estate holdings (green), and other assets net of liabilities (light blue). Other assets include consumer durable goods, nonprofit organizations’ fixed assets, and financial assets other than corporate equity.

Household debt increased at an annual rate of 4.4 percent in the second quarter of 2016. Consumer credit grew 6.4 percent, while mortgage debt (excluding charge-offs) grew 2.5 percent at an annual rate.

Domestic nonfinancial debt outstanding was $46.3 trillion at the end of the second quarter of 2016, of which household debt was $14.5 trillion, nonfinancial business debt was $13.2 trillion, and total government debt was $18.6 trillion. The figure plots the 4-quarter moving average percent growth rate of debt outstanding for domestic nonfinancial sectors at a quarterly frequency. The growth rate of debt is calculated as the seasonally adjusted flow divided by the seasonally adjusted level in the previous period, multiplied by 100. In the Financial Accounts, debt equals the sum of debt securities and loans.

Domestic nonfinancial debt growth was 4.4 percent at a seasonally adjusted annual rate in the second quarter of 2016, down from an annual rate of 5.4 percent in the previous quarter.

Nonfinancial business debt rose at an annual rate of 4.1 percent in the second quarter, down from an annual rate of 9.4 percent in the previous quarter.

State and local government debt rose at an annual rate of 2.2 percent in the second quarter of 2016, up from an annual growth rate of 0.8 percent in the previous quarter.

Federal government debt increased 5.0 percent at a seasonally adjusted annual rate in the second quarter of 2016.

Rate Hikes Will Be the Least of Market Worries – Moody’s

Moody’s says the Fed does not set interest rates in a vacuum. Indeed, the federal funds rate is shaped by a host of drivers that are hardly limited to labor market conditions.

Despite warnings from high-ranking Fed officials that ultra-low interest rates are not forever, recent soundings of business activity, as well as the nearness of November 8’s Presidential election, weigh against a hiking of the federal funds rate prior to the FOMC’s December 14 meeting. Moreover, recent data question whether 2016 will be home to even a single rate hike.

In a September 12 speech, Fed governor Lael Brainard presented a convincing case favoring an extended stay by exceptionally low benchmark interest rates. On several occasions, Governor Brainard challenged the wisdom of a preemptive rate hike that intends to thwart inflation before it takes hold. Given “the absence of accelerating inflationary pressures” and the limited scope for lowering of fed funds in the event recession risks rise, Brainard argues for the continuation of a highly accommodative monetary policy. Basically, the macroeconomic costs of mistakenly hiking rates too early are viewed as well exceeding the potential inflationary costs of waiting too long to confront inflation. The damage done by a premature rate hike may be harder to repair than the damage resulting from above-target price inflation.

However, there is an alternative view that views ultra-low interest rates as doing more harm than good because of how cheap money (i) boosts savings in order to compensate for negligible interest income and (ii) forces investors to purchase riskier assets offering higher, though volatile, returns.

Futures now sense 2016 will end without a rate hike

As measured by the CME Group’s FedWatch tool, fed funds futures assign an implied probability of only 12% to a hiking of fed funds at the September 21 meeting of the FOMC. Thereafter, the implied likelihood barely rises to 20% for the November 2 meeting and climbs no higher than 47% for the FOMC’s deliberations of December 14. For now, the futures market does not expect a single rate hike for 2016.

The latest declines by the implied probabilities of rate hikes at the FOMC’s remaining three meetings for 2016 stemmed from lower than expected August readings for retail sales and industrial production. Despite the latest indications of subpar business sales, US equities rallied. Moreover, an accompanying drop by the VIX index hinted a narrowing of the high-yield spread that recently widened from September 8’s 18-month low of 508 bp to September 14’s 538 bp. Nevertheless, at some point, the corporate earnings outlook will overrule the now predominant influence of Fed policy. Unless business sales soon accelerate sufficiently, market participants will begin to fret over the adequacy of earnings for 2016’s final quarter and all of 2017.

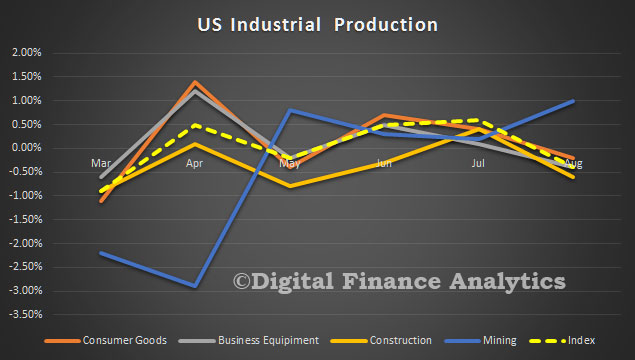

US Production Index Lower Than Expected

Latest figures from the US Federal Reserve shows that industrial production decreased 0.4 percent in August after rising 0.6 percent in July. The market reacted to this data, taking it as an indicator that a rate rise was less likely in the short term.

Manufacturing output declined 0.4 percent in August, reversing its increase in July; the level of the index in August is little changed from its level in March. Following two consecutive monthly increases, the index for utilities fell back 1.4 percent in August. Even so, the index was 1.7 percent above its year-earlier level, as hot temperatures this summer boosted the usage of air conditioning.

The output of mining moved up 1.0 percent in August, its fourth consecutive monthly increase following an extended downturn; the index, however, was still about 9 percent below its year-ago level. At 104.4 percent of its 2012 average, total industrial production in August was 1.1 percent lower than its year-earlier level. Capacity utilization for the industrial sector decreased 0.4 percentage point in August to 75.5 percent, a rate that is 4.5 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2015) average.

Market Groups

The indexes for all major market groups declined in August. The output of consumer goods decreased 0.2 percent as a result of a large drop in consumer energy products and a small decline in consumer non-energy nondurables. The output of consumer durables was unchanged; a gain in automotive products was offset by declines in all of its other components. Business equipment posted a decrease of 0.4 percent, as gains of 1 percent or more for transit equipment and for information processing equipment were outweighed by a cutback of nearly 2 percent for industrial and other equipment. The output of defense and space equipment declined 0.6 percent. The indexes for construction supplies and business supplies moved down 0.6 percent and 0.8 percent, respectively. The production of materials decreased 0.5 percent: Both durable and energy materials posted declines, while the output of nondurable materials was unchanged. The reduction in the index for durable materials reflected similarly sized losses across all its major categories.

Industry Groups

Manufacturing output declined 0.4 percent in August; the index was also 0.4 percent below its level of a year earlier. In August, the production of nondurables moved down 0.2 percent, and the indexes for durables and for other manufacturing (publishing and logging) fell 0.6 percent and 0.7 percent, respectively. Many durable goods industries posted declines of nearly 1 percent or more, with the largest drop, 1.9 percent, recorded by machinery. Within nondurables, gains for food, beverage, and tobacco products and for paper were more than offset by declines elsewhere; the largest decrease, 2.1 percent, was recorded by textile and product mills.

The index for mining moved up 1.0 percent in August, with a decline in coal mining outweighed by increases in the indexes for oil and gas extraction, for oil well drilling and servicing, and for metal ore and nonmetallic mineral mining.

Capacity utilization for manufacturing decreased 0.4 percentage point in August to 74.8 percent, a rate that is 3.7 percentage points below its long-run average. The operating rate for nondurables moved down 0.2 percentage point; the rates for durables and for other manufacturing (publishing and logging) each declined 0.5 percentage point. The operating rate for mining moved up 1.0 percentage point to 76.2 percent, while the rate for utilities decreased 1.3 percentage points to 80.4 percent.