Just released by the FED, rates are on hold, because of concerns about global growth and current levels of employment and inflation. In addition they hint at lower rates for longer.

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in July suggests that economic activity is expanding at a moderate pace. Household spending and business fixed investment have been increasing moderately, and the housing sector has improved further; however, net exports have been soft. The labor market continued to improve, with solid job gains and declining unemployment. On balance, labor market indicators show that underutilization of labor resources has diminished since early this year. Inflation has continued to run below the Committee’s longer-run objective, partly reflecting declines in energy prices and in prices of non-energy imports. Market-based measures of inflation compensation moved lower; survey-based measures of longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable.

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. Recent global economic and financial developments may restrain economic activity somewhat and are likely to put further downward pressure on inflation in the near term. Nonetheless, the Committee expects that, with appropriate policy accommodation, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace, with labor market indicators continuing to move toward levels the Committee judges consistent with its dual mandate. The Committee continues to see the risks to the outlook for economic activity and the labor market as nearly balanced but is monitoring developments abroad. Inflation is anticipated to remain near its recent low level in the near term but the Committee expects inflation to rise gradually toward 2 percent over the medium term as the labor market improves further and the transitory effects of declines in energy and import prices dissipate. The Committee continues to monitor inflation developments closely.

To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that the current 0 to 1/4 percent target range for the federal funds rate remains appropriate. In determining how long to maintain this target range, the Committee will assess progress–both realized and expected–toward its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial and international developments. The Committee anticipates that it will be appropriate to raise the target range for the federal funds rate when it has seen some further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term.

The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. This policy, by keeping the Committee’s holdings of longer-term securities at sizable levels, should help maintain accommodative financial conditions.

When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent. The Committee currently anticipates that, even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels the Committee views as normal in the longer run.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Janet L. Yellen, Chair; William C. Dudley, Vice Chairman; Lael Brainard; Charles L. Evans; Stanley Fischer; Dennis P. Lockhart; Jerome H. Powell; Daniel K. Tarullo; and John C. Williams. Voting against the action was Jeffrey M. Lacker, who preferred to raise the target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points at this meeting.

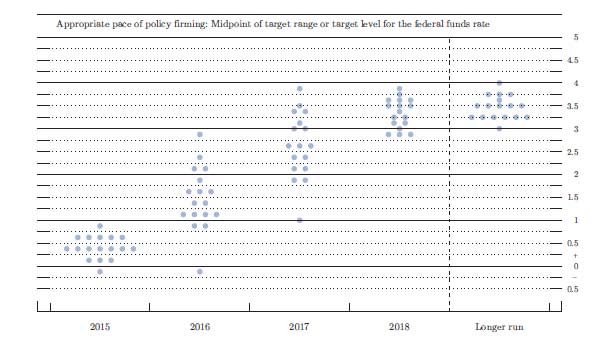

The released economic data included a chart on members future expectations. Each shaded circle indicates the value (rounded to the nearest 1/8 percentage point) of an individual

Each shaded circle indicates the value (rounded to the nearest 1/8 percentage point) of an individual

participant’s judgment of the midpoint of the appropriate target range for the federal funds rate or the appropriate target level for the federal funds rate at the end of the specified calendar year or over the longer run.