The ABS released their wage price index to December quarter 2014, showing continued slow wage growth. The Private sector index rose 0.6% and the Public sector rose 0.7%. The All sectors quarterly rise was 0.6%, which marks the ninth consecutive All sectors quarterly increase between 0.6% and 0.7%.

The Private sector through the year rise to the December quarter 2014 of 2.4% was smaller than the Public sector rise of 2.7%. Through the year, All sectors rose 2.5%. The CPI is now down to 1.7%, so wages are running slightly ahead.

In original terms, wages rose 0.6% in the December quarter 2014 for All sectors. The Private sector rose 0.5% in the December quarter 2014, smaller than the Public sector rise of 0.7%. The All sectors through the year rise was 2.6%. The Private sector rose 2.5% and the Public sector 2.7%.

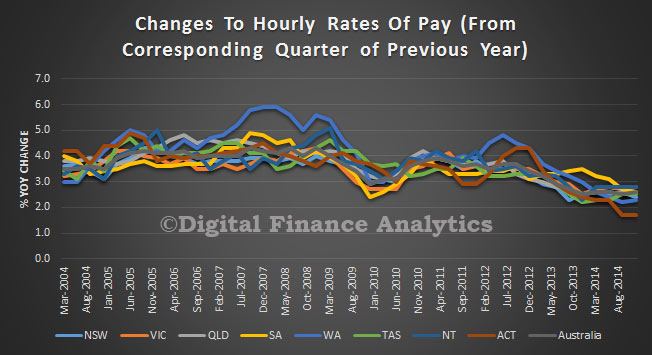

The largest quarterly rise of 0.7% was recorded by Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. Tasmania recorded the smallest quarterly rise of 0.3%. Rises through the year ranged from 1.7% for the Australian Capital Territory, to 2.8% for Victoria and the Northern Territory.

In the Private sector, the quarterly rise for South Australia of 0.7% was the largest quarterly rise of all states and territories. The smallest quarterly rise was 0.3%, recorded for Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory. Rises through the year in the Private sector ranged from 2.0% for Western Australia to 2.7% for Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Wages growth in Western Australia continued to ease in the December quarter 2014. For the fourth quarter in a row the quarterly growth was smaller than the same quarter the year before.

In the Public sector, Western Australia recorded the largest quarterly rise of 1.5%, with Tasmania recording the smallest quarterly rise of 0.2%. Western Australia and the Northern Territory both recorded the largest through the year Public sector rise of 3.5%. For the second quarter in a row, the smallest through the year rise for the Public sector was recorded by the Australian Capital Territory (1.4%). Commonwealth government employee pay changes are most evident in the wages growth reported for the Australian Capital Territory. Public sector wages growth in other states and territories is mostly driven by regularly scheduled State and Local government pay increases.

By Industry, Information media and telecommunications recorded the largest All sectors quarterly rise of 1.2%. The smallest quarterly rise for All sectors of 0.2% was recorded by Accommodation and food services.

The All sectors through the year rises for the December quarter 2014 ranged from 1.9% for Professional scientific and technical services to 3.4% for Education and training and Arts and recreation services.

In the Private sector, Information media and telecommunications recorded the largest quarterly rise of 1.3%. Public administration and safety recorded the smallest rise of 0.1%. Rises through the year in the Private sector ranged from 1.9% for Professional scientific and technical services to 3.9% for Arts and recreation services.

In the Public sector, Education and training recorded the largest quarterly rise of 1.2%. The smallest quarterly rise of 0.4% was recorded by Professional scientific and technical services and Electricity, gas, water and waste services. Rises through the year in the Public sector ranged from 3.4% for Education and training to 1.5% for Professional scientific and technical services, the equal smallest through the year rise in this industry since the commencement of the Wage Price Index.