We got some more data on the state of the Australian Economy today from RBA Deputy Governor, Guy Debelle, which built on the recently released Statement on Monetary Policy (SMP).

There were four items which caught my attention.

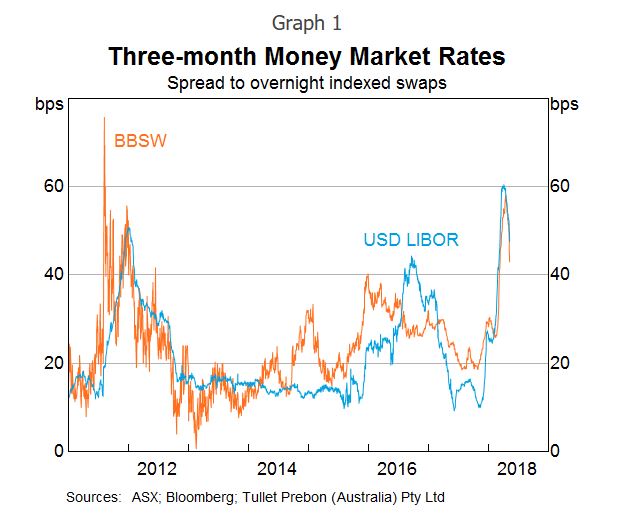

First, the recent rise in money market interest rates in the US, particularly LIBOR. He said there are a number of explanations for the rise, including a large increase in bill issuance by the US Treasury and the effect of various tax changes on investment decisions by CFOs at some US companies with large cash pools.  This rise in LIBOR in the US has been reflected in rises in money market rates in a number of other countries, including here in Australia. This is because the Australian banks raise some of their short-term funding in the US market to fund their $A lending, so the rise in price there has led to a similar rise in the cost of short-term funding for the banks here; that is, a rise in BBSW. This increases the wholesale funding costs for the Australian banks, as well as increasing the costs for borrowers whose lending rates are priced off BBSW, which includes many corporates.

This rise in LIBOR in the US has been reflected in rises in money market rates in a number of other countries, including here in Australia. This is because the Australian banks raise some of their short-term funding in the US market to fund their $A lending, so the rise in price there has led to a similar rise in the cost of short-term funding for the banks here; that is, a rise in BBSW. This increases the wholesale funding costs for the Australian banks, as well as increasing the costs for borrowers whose lending rates are priced off BBSW, which includes many corporates.

However, he says the effect to date has not been that large in terms of the overall impact on bank funding costs. It is not clear how much of the rise in LIBOR (and hence BBSW) is due to structural changes in money markets and how much is temporary. In the last couple of weeks, these money market rates have declined noticeably from their peaks. But to my mind it shows one of the potential risks ahead.

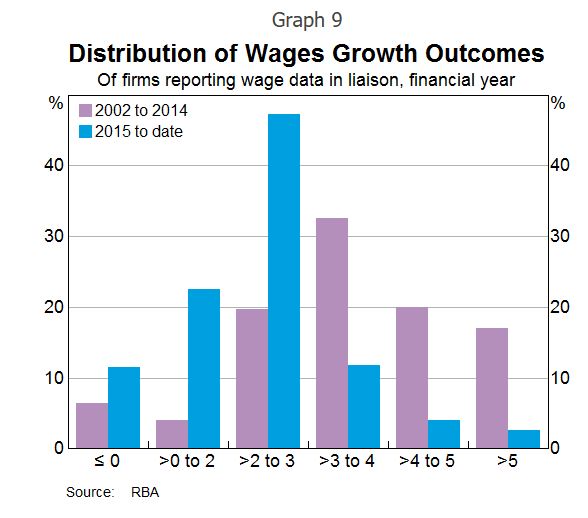

Second the gradual decline in spare capacity is expected to lead to a gradual pick-up in wages growth. But when? The experience of other countries with labour markets closer to full capacity than Australia’s is that wages growth may remain lower than historical experience would suggest. In Australia, 2 per cent seems to have become the focal point for wage outcomes, compared with 3–4 per cent in the past. Work done at the Bank shows the shift of the distribution of wages growth to the left and a bunching of wage outcomes around 2 per cent over the past five years or so.

The RBA says that recent data on wages provides some assurance that wages growth has troughed. The majority of firms surveyed in the Bank’s liaison program expect wages growth to remain broadly stable over the period ahead. Over the past year, there has been a pick-up in firms expecting higher wage growth outcomes. Some part of that is the effect of the Fair Work Commission’s decision to raise award and minimum wages by 3.3 per cent. They suggest there are pockets where wage pressures are more acute. But, while those pockets are increasing gradually, they remain fairly contained at this point

The RBA says that recent data on wages provides some assurance that wages growth has troughed. The majority of firms surveyed in the Bank’s liaison program expect wages growth to remain broadly stable over the period ahead. Over the past year, there has been a pick-up in firms expecting higher wage growth outcomes. Some part of that is the effect of the Fair Work Commission’s decision to raise award and minimum wages by 3.3 per cent. They suggest there are pockets where wage pressures are more acute. But, while those pockets are increasing gradually, they remain fairly contained at this point

But he concluded that there is a risk that it may take a lower unemployment rate than we currently expect to generate a sustained move higher than the 2 per cent focal point evident in many wage outcomes today.

Third, he takes some comfort from the fact that arrears rates on mortgages remain low. This despite Wayne Byres comment a couple of months back, that at these low interest rates, defaults should be even lower! Debelle said that even in Western Australia, where there has been a marked rise in unemployment and where house prices have fallen by around 10 per cent, arrears rates have risen to around 1½ per cent, which is not all that high compared with what we have seen in other countries in similar circumstances and earlier episodes in Australia’s history. To which I would add, yes but interest rates are ultra-low. What happens if rates rise as we discussed above or unemployment rises further?

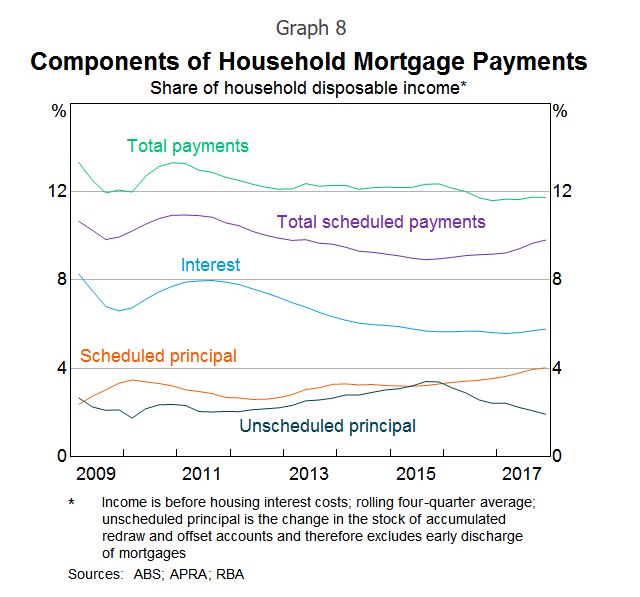

Finally, the interest rate resets on interest-only loans will potentially require mortgage payments to rise by nearly 30–40 per cent for some borrowers. There are a number of these loans whose interest-only periods expire this year. It is worth noting that there were about the same number of loans resetting last year too. The RBA says there are quite a few mitigants which will allow these borrowers to cope with this increase in required payments, including the prevalence of offset accounts and the ability to refinance to a principal and interest loan with a lower interest rate. While some borrowers will clearly struggle with this, our expectation is that most will be able to handle the adjustment so that the overall effect on the economy should be small.

This switch away from interest-only loans should see a shift towards a higher share of scheduled principal repayments relative to unscheduled repayments for a time. We are seeing that in the data. It also implies faster debt amortisation, which may have implications for credit growth.

And there is a risk of a further tightening in lending standards in the period ahead. This may have its largest effect on the amount of funds an individual household can borrow, more than the effect on the number of households that are eligible for a loan. This, in turn, means that credit growth may be slower than otherwise for a time. That he says has more of an implication for house prices, than it does for the outlook for consumption. To which I would add, yes, but consumption is being funded by raiding deposits and higher debt. Hardly sustainable.

And there is a risk of a further tightening in lending standards in the period ahead. This may have its largest effect on the amount of funds an individual household can borrow, more than the effect on the number of households that are eligible for a loan. This, in turn, means that credit growth may be slower than otherwise for a time. That he says has more of an implication for house prices, than it does for the outlook for consumption. To which I would add, yes, but consumption is being funded by raiding deposits and higher debt. Hardly sustainable.

So in summary, there are still significant risks in the system and the net effect could well drive prices lower, as credit tightens. And I see the RBA slowly turning towards the views we have held for some time. I guess if there is more of a down turn ahead, they can claim they warned us (despite their settings setting up the problem in the first place).