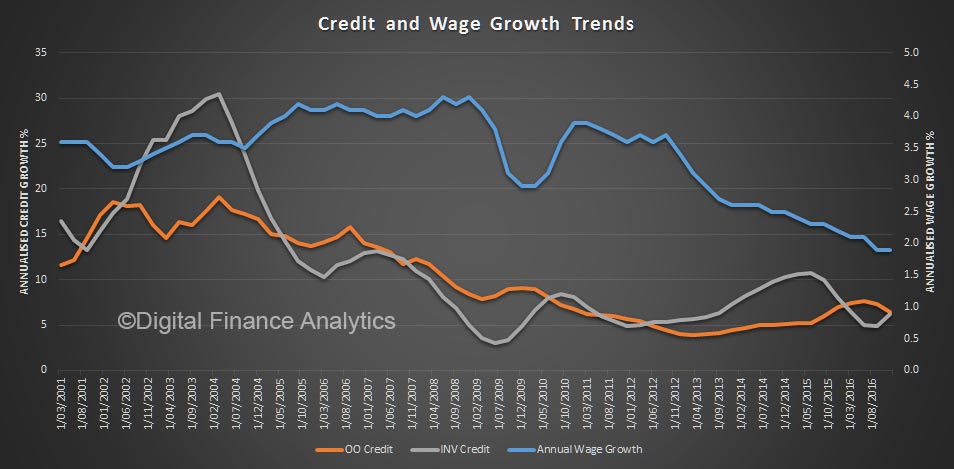

You only have to look at the trends on housing credit growth and wage growth to see the problem. Using data from the ABS and RBA, we can see that in recent times credit to households for housing has been growing significantly faster than wage growth (note the two different scales) whereas in the 2000’s, before the GFC hit, wage growth was higher, and able to support such credit growth. No wonder household debt is at a record high.

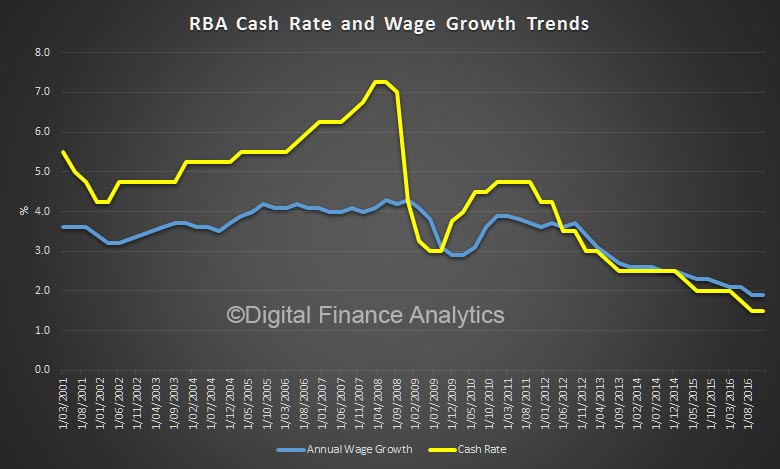

The other perspective is the cash rate, which has been cut to an all time low, and we see wage growth and rates trending in the same direction.

The other perspective is the cash rate, which has been cut to an all time low, and we see wage growth and rates trending in the same direction.

Whilst you can argue that lower rates means repayments are lower for many, the gearing effect of larger mortgages off the back of the home price boom, has created a major problem, with many households close to the edge at current low interest rates, and with low wage growth, no sign of this pressure relenting. Indeed, if rates rise (either officially or from market pressure) significantly more households will be stressed. Many will also struggle to pay off the capital.

Whilst you can argue that lower rates means repayments are lower for many, the gearing effect of larger mortgages off the back of the home price boom, has created a major problem, with many households close to the edge at current low interest rates, and with low wage growth, no sign of this pressure relenting. Indeed, if rates rise (either officially or from market pressure) significantly more households will be stressed. Many will also struggle to pay off the capital.

These charts, together should have been a warning to regulators. The settings are wrong.

I think you can argue that we should be aiming for credit growth to match income growth, to stop the rot – but consider the impact on the banks (who rely on mortgage growth for profitability) home prices (a reduction in mortgage availability will force home prices lower) and housing affordability (credit rationing would lift the price of loans).

Even small adjustments might well create the conditions for a property market crash, with all the consequences that follow.

There is an old joke, when a driver stops to ask a local for directions, and the answer is “if I were you, I would not start from here”. The regulators have the same problem!