The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability Report April 2018, includes a chapter on housing. They look at the global hike in home prices and attribute much of it to the globalisation of finance.

Australian cities are well up the list in terms of gains and also global impact. However, to me they missed the key link. It is the ultra-low interest rates result from QE, across many of these markets, either formally, or informally, which have driven the home prices higher; it is credit led. Sure credit can move across borders, but it was monetary policy which has created the problem.

The fall out of higher international finance rates will now flow directly to our doors, thanks to this same globalisation. Not pretty. So they also warn of risks as this all unwinds.

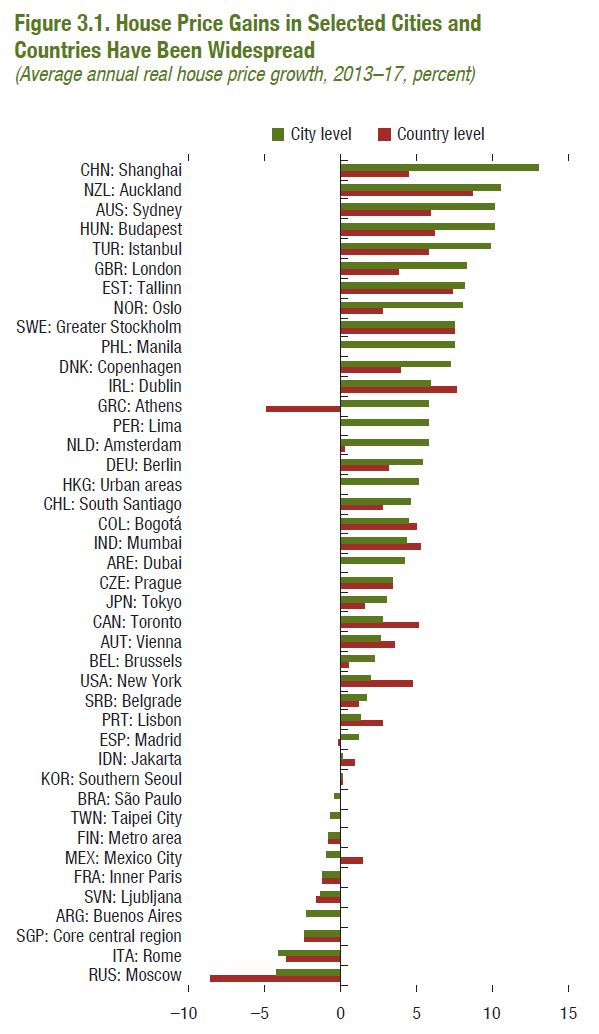

The chapter finds an increase in house price synchronization, on balance, for 40 advanced and emerging market economies and 44 major cities.

Countries’ and cities’ exposure to global financial conditions may explain rising house price synchronization. Moreover, cities in advanced economies may be particularly exposed to global financial conditions, perhaps because they are integrated with global financial markets or are attractive to global investors searching for yield or safe assets.

Policymakers cannot ignore the possibility that shocks to house prices elsewhere will affect markets at home. House price synchronization in and of itself may not warrant policy intervention, but the chapter finds that heightened synchronicity can signal a downside tail risk to real economic activity.

Macroprudential policies seem to have some ability to influence local house price developments, even in countries with highly synchronized housing markets, and these measures may also be able to reduce a country’s house price synchronization. Such unintended effects are worth considering when evaluating the trade-offs of implementing macroprudential and other policies.