During the GFC, a number of banks were bailed out to stop them failing using tax payer funds. Whilst the immediate crisis passed, there is still a residual level of support to banks, and an expectation that if they got into financial difficulty, they would be bailed out. This allows them to gain funding cost advantages (priced closer to their countries credit rating). The level of support though is unclear, and the cost to society not fully understood.

So the newly released working paper from the IMF – Whose Credit Line is it Anyway: An Update on Banks’ Implicit Subsidies makes interesting reading.

It is safe to say that the recent designation of particular institutions as systemically important by regulators has had a non-negative impact on the perception that these institutions would be assisted in the event of a crisis. So-called living wills are intended to render the default of these institutions manageable but the process remains murky, failing to establish confidence that a default could be managed in a controlled manner. Indeed, U.S. regulators recently ruled that many of the current plans, submitted by the banks themselves, remain non-credible.

Therefore, the issue of preventing public sector involvement in the resolution remains unsolved. The other primary pillar of the reform agenda is to decrease the probability of such events occurring in the first place, most notably via higher capital requirements. In addition to the direct benefit of making the institutions safer, this reduction in default probabilities has the benefit of allocating potential losses to a greater extent to shareholders and thus reducing the implicit subsidies received by the institutions.

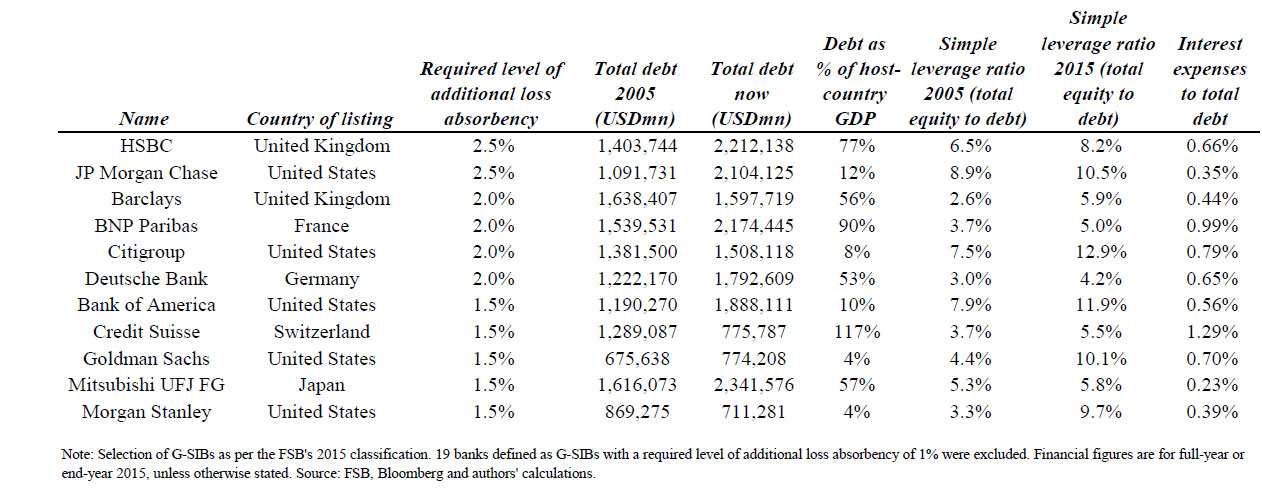

They use an option pricing model to assess the value of the implicit support provided to a sample of the 11 global systemically-important (G-SIB) banks with a surcharge of 1.5 percent or higher, as defined by the FSB in 2015. Here are the banks studied.

They find that the baseline result shows total subsidies for the 11 banks peaked at 135bn USD in 2009 before declining to 62bn USD last year.

They find that the baseline result shows total subsidies for the 11 banks peaked at 135bn USD in 2009 before declining to 62bn USD last year.

Therefore the weighted average subsidy for eleven G-SIBs peaked at 70 bps during the crisis and has declined to approximately 35 bps in the post-crisis era, which is in line with the literature although towards the lower end of the range.

They conclude that while these subsidies have declined in the post-crisis era as volatility has declined and capital levels have increased, they remain non-trivial. Even conservative parameterizations of default and loss probabilities lead to macroeconomically significant figures.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.