The BIS just published an interesting working paper – “The impact of macroprudential housing finance tools in Canada“.

Do policies which seek to regulate serviceability, such as debt to income, or debt servicing ratios, work better than loan to value controls? A highly relevant question given the fact that some central banks are going down the debt to income approach (e.g Bank of England has implement high DTI thresholds) and Reserve Bank NZ is exploring this at the moment).

It seems from their research that income related constraints work well for higher income households, but loan to value methods work better for households with more constrained incomes. So perhaps DTI measures should be targetted at more wealthy households seeking larger loans.

This was a paper produced as part of the BIS Consultative Council for the Americas (CCA) research project on “The impact of macroprudential policies: an empirical analysis using credit registry data” implemented by a Working Group of the CCA Consultative Group of Directors of Financial Stability (CGDFS).

The paper combines loan-level administrative data with household-level survey data to analyze the impact of recent macroprudential policy changes in Canada using a microsimulation model of mortgage demand of first-time homebuyers.

They found that policies targeting the loan-to-value ratio have a larger impact on demand than policies targeting the debt-service ratio, such as amortization. In addition, they show that loan-to-value policies have a larger role to play in reducing default than income-based policies.

The results of the experiments suggest that wealth constraints are more effective than income constraints at affecting mortgage demand, particularly on the extensive margin, for a given proportional change and the given starting points of policy parameters (95% maximum LTV and maximum 25-year amortization for insured mortgages).

Income constraints, however, are just as effective as wealth constraints for high-wealth homebuyers. The focus of the empirical analysis and the model, however, is on mortgage demand, and ignores some aspects of the general market for housing as well as potential supply effects.

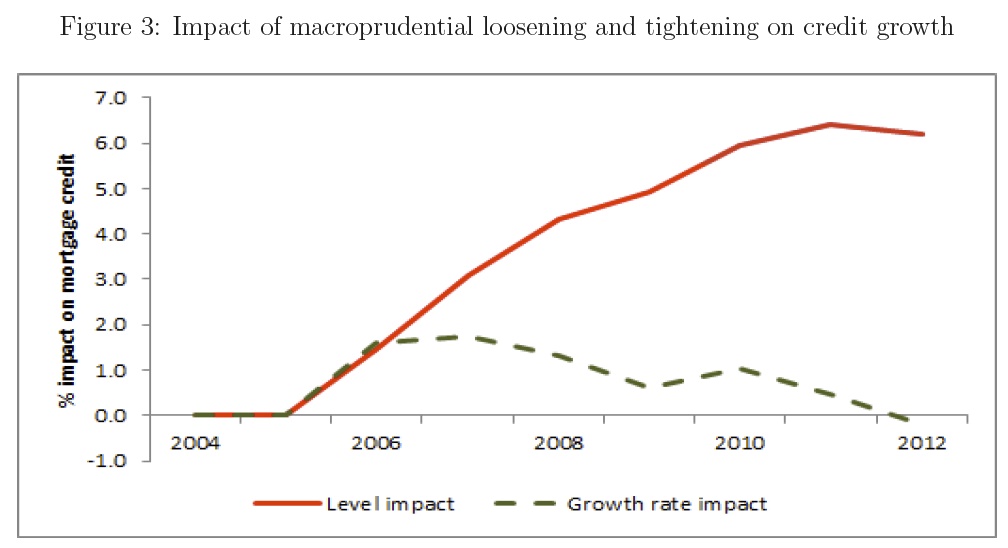

From changes in consumer demand, we fnd that LTV constraints, which work through the wealth channel, are effective housing finance tools. Given that the average household is able to meet changes in cash flow, we conclude that, at least with the types of changes we observe to amortization, that changes directed at household repayment constraint are less effective. Households are attracted to these products, however, they are not binding.

An important contribution of this paper is the use of microsimulation modeling to capture the interactions of multiple policy tools and the non-linearities in consumer responses. This model imposes some structure on how we interpret the data while still being highly flexible in capturing nonlinear responses that more traditional, rational forward-looking dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models generally have difficulty capturing. The model allows us to map the impact of a policy change on the percentage of FTHBs who enter the market and their demand for credit. The results of our microsimulation model suggest that the wealth constraint has the largest impact on the number of FTHBs who enter the housing market and amount of debt that they hold. However, the impact of changes in amortization, which affect the income constraint, do affect high-wealth households. Finally, we show that LTV policies seem to reduce the impact of interest rate shocks on household vulnerabilities relative to income-based policies.

A caveat of our results is that we have taken as given that lenders are able to change the supply of credit exogenously in response to changes in macroprudential policy. This appears

reasonable, given that banks do not face default risk in the Canadian (insured) mortgage market. However, if there is a tightening, banks might react strategically to price mortgages

in a way that partially offsets changes in macroprudential policies. More importantly, we do not capture general equilibrium effects. A relaxation of mortgage insurance guidelines leads to entry of FTHBs, which can lead to house price appreciation, which leads to further entry and greater house price appreciation. This can affect both current and future mortgage demand in a way that is not captured in the model.

Note: BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS.