When the ratings agency S&P Global downgraded its outlook for the Australian economy earlier this week, it would have caught many people by surprise.

That hasn’t been the story coming out of Canberra in recent months. Treasurer Scott Morrison put on a sterling display of optimism during budget week, telling us that not only were lots of jobs being created, but the tax revenue flowing from those jobs would help bring the budget back to surplus.

Sadly, S&P has the more accurate picture. As noted on Wednesday, it sees our economy as “very high risk” due to “strong growth in private sector debt and residential property prices in the past four years”.

But the housing bubble is only half the story. Times have changed from the years when a large mortgage would quickly get easier to service as inflation eroded the real value of the debt.

Now, other forces of erosion are at work. Number-crunching last week’s jobs data from the Bureau of Statistics shows that it’s not debts that are eroding, but the number of hours of work available in the economy.

When the Treasurer quotes the jobs data, he tends to focus on the ‘seasonally adjusted’ unemployment rate, which fell from 5.8 to 5.7 per cent in April – the more reliable ‘trend’ figure remains stuck at 5.8 per cent.

But it’s what is happening behind those figures that is worrying.

First, there’s the ongoing trend towards part-time work. In the past year, the 49,300 full-time jobs created were easily eclipsed by 102,800 part-time jobs.

The growth rate for part-time jobs is three times that for full-time jobs, and if that trend continues over the next year, many heavily indebted households will start to reach breaking point.

The debt problem

Australia now has a middle strata of homeowners, between renters and those who’ve paid off their mortgages, who are carrying historically high levels of debt.

Not only are their debts not being significantly eroded by inflation, but the purchase price of homes in most cities continues to climb, loading up new generations of home buyers with even bigger debts.

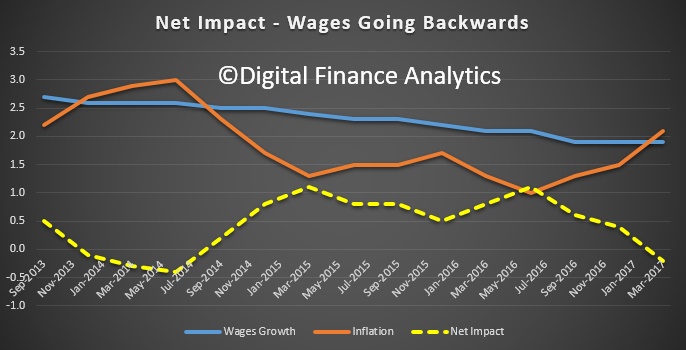

That’s what S&P is concerned about. Mortgage holders are also struggling with two other trends – below-inflation wages growth, and the fall in hours worked revealed by the ABS last week.

While for an individual, having a part-time job is a lot better than none at all, for many families the problem of having one or even two breadwinners wanting more hours is growing.

This is what you need

Australia’s population is growing at a rapid annual rate of 1.4 per cent.

The workforce doesn’t grow quite that quickly due to the ageing population profile, but it’s not far behind – 1.36 per cent in the past year according to the ABS.

If workers’ hours had remained constant on average, the total hours worked would have risen by 22.5 million in the past year to reflect the expanding workforce.

What we saw last week was a fall of two million hours in the month of April, and growth over the year at half the level it should be – 10.4 million hours.

Those figures say a lot more about how the economy is progressing than simple ‘jobs’ figures, but even the job figures fell behind.

There have been 152,100 jobs created in the past year (to April), but the workforce has grown by 172,400 people in the same period. That is, more people than jobs available.

Household debt, meanwhile, continues its march higher. The average household debt is 190 per cent of disposable income, according to the RBA.

It’s important to remember, too, that most of that debt is concentrated in the one-third of households which have a mortgage.

That’s the slice of middle Australia for whom celebrations over a ‘fall in unemployment’ will make no sense.

RBA figures show that one third of mortgage-holders has less than a one-month buffer in the household finances before they fall into arrears.

That’s a risk for them, but also for the economy.

S&P is only telling us what the economists in the Department of Treasury already know, but the politicians aren’t keen to say.