The Bank for International Settlements has published their 87th Annual Report, to March 2017. They say there are encouraging signs of economic recovery, but point to risks from high household debt and over-reliance on monetary policy. They call for a rebalancing of policy towards structural reform.

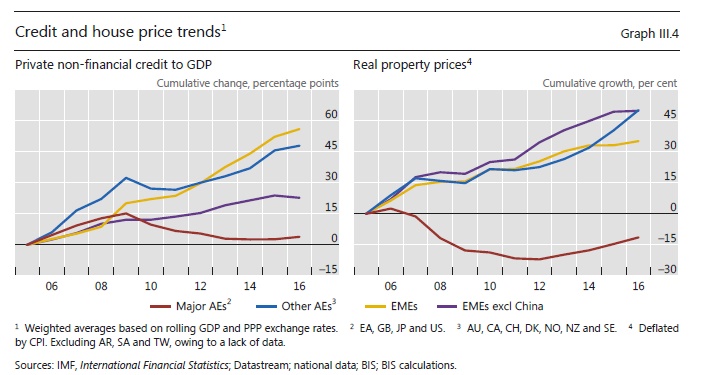

They underscore the risks which result from over investment in housing, and excessive credit and make the point that in Australia, Canada, Sweden and Switzerland, household debt rose by 2–3 percentage points in 2016, to 86–128% of GDP. True growth comes from productive economic investment, not ever more housing debt, which becomes a real problem should interest rates rise.

They say that high levels of debt servicing will have a dampening impact on future economic growth.

They say that high levels of debt servicing will have a dampening impact on future economic growth.

It is well recognised that household borrowing is an important aspect of financial inclusion and can play useful economic roles, including smoothing consumption over time. At the same time, rapid household credit growth has featured prominently in financial cycle booms and busts. For one, household debt – or debt more generally – outpacing GDP growth over prolonged periods is a robust early warning indicator of financial stress.

The adverse effects of excessive credit growth can also be magnified by the economy’s supply side response. For example, banks’ stronger willingness to extend mortgages may feed an unsustainable housing boom and overinvestment in the construction sector, which may crowd out investment opportunities in higher-productivity sectors. Credit booms tend to go hand in hand with a misallocation of resources – most notably towards the construction sector – and a slowdown in productivity growth, with long-lasting adverse effects on the real economy.

Additional risks to consumption arise from elevated levels of household debt, in particular given the prospect of higher interest rates. Recent evidence from a sample of advanced economies suggests that increasing household debt in relation to GDP has boosted consumption in the short term, but this has tended to be followed by sub-par medium-term macroeconomic performance.

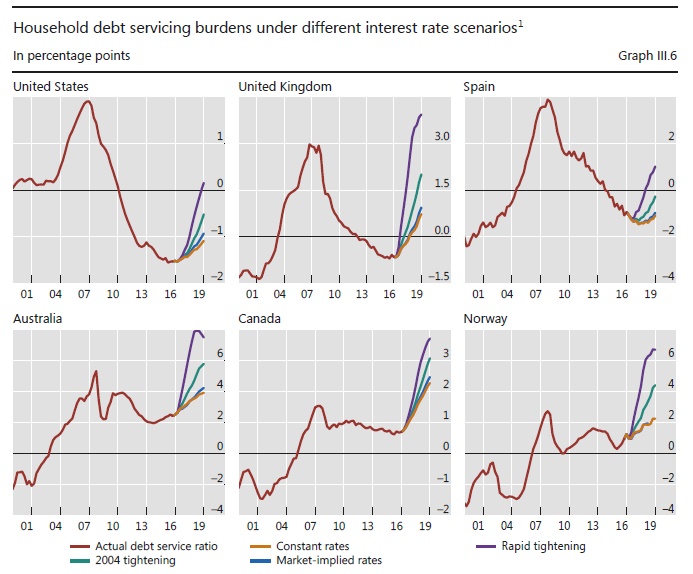

It is possible to assess the effect of higher interest rates on debt service burdens through illustrative simulations. These capture the dynamic relationships between the two components of the DSR (the credit-to-income ratio and the nominal interest rate on debt), real residential property prices, real GDP and the three month money market interest rate. Crisis-hit countries, where households have deleveraged post-crisis, appear relatively resilient to rising interest rates. In most cases considered, debt service burdens remain close to long-run averages even in a scenario in which short-term interest rates increase rapidly to end-2007 levels. By contrast, in countries that experienced rapid rises in household debt over recent years, DSRs are already above their historical average and would be pushed up further by higher interest rates.