Fed Governor Jerome H. Powell spoke on “Low Interest Rates and the Financial System“. Monetary policy may sometimes face trade offs between macroeconomic objectives and financial stability. He argues that”low for long” interest rates have supported slow but steady progress to full employment and stable prices, which has in turn supported financial stability. But, there are difficult trade offs to manage. Over time, low rates can put pressure on the business models of financial institutions. And low rates can lead to excessive leverage and broadly unsustainable asset prices.

Whilst there are times when all of these objectives are aligned. For example, the Fed’s initial unconventional policies supported both market functioning and aggregate demand. More broadly, post-crisis monetary policy supported asset values, reduced interest payments, and increased both employment and income. All of these effects are likely to have limited defaults and foreclosures and bolstered the balance sheets of households, businesses, and financial intermediaries, leaving the system more robust.

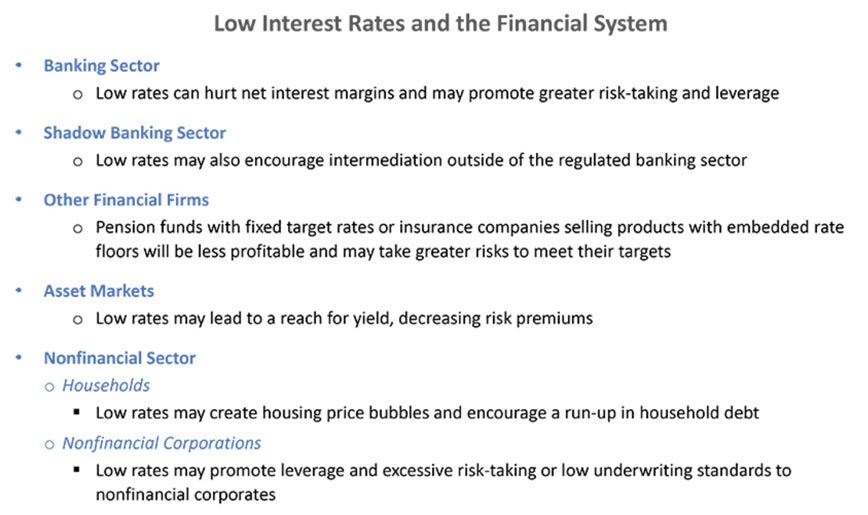

But at times there will be tradeoffs. Low-for-long interest rates can have adverse effects on financial institutions and markets through a number of plausible channels.

After all, low interest rates are intended to encourage some risk-taking. The question is whether low rates have encouraged excessive risk-taking through the buildup of leverage or unsustainably high asset prices or through misallocation of capital. That question is particularly important today. Historically, recessions often occurred when the Fed tightened to control inflation. More recently, with inflation under control, overheating has shown up in the form of financial excess. Core PCE inflation remained close to or below 2 percent during both the late-1990s stock market bubble and the mid-2000s housing bubble that led to the financial crisis. Real short- and long-term rates were relatively high in the late-1990s, so financial excess can also arise without a low-rate environment. Nonetheless, the current extended period of very low nominal rates calls for a high degree of vigilance against the buildup of risks to the stability of the financial system.If we look at the channels listed here, the picture is mixed, but the bottom line is that there has not been an excessive buildup of leverage, maturity transformation, or broadly unsustainable asset prices.

Low long-term interest rates have weighed on profitability in the financial sector, although firms have so far coped with those pressures. Net interest margins (NIMs) for most banks have held up surprisingly well. NIMs have moved down for the largest banks

Return on assets, has recovered but remains below pre-crisis levels. Life insurers have substantially underperformed the broader equity market since 2007, suggesting that investors see the low-rate environment as a drag on profitability for the industry. Even so, data on asset portfolios do not suggest that life insurers have increased risk-taking. The same is true for banks. Both the regulatory environment and banks’ own attitudes toward risk following the financial crisis have helped ensure that the largest banks have not taken on excessive credit or duration risks relative to their capital cushions.

Low rates have provided support for asset valuations–indeed, that is part of their design. But I do not see valuations as significantly out of line with historical experience. Equity prices have recently increased considerably, pushing the forward price-earnings ratio further above its historical median.

And equity premiums –the expected return above the risk-free rate for taking equity risk– have declined, but are not out of line with historical experience.

In the nonfinancial sector, valuation pressures are most concerning when leverage is high, particularly in real estate markets. Residential real estate valuations have been in line with rents and household incomes in recent years, and the ratio of mortgage debt to income is well below its pre-crisis peak and still declining. In contrast, valuations in commercial real estate are high in some markets. And in the nonfinancial corporate sector, gross leverage is high by historical standards. Low long-term rates have encouraged corporate debt issuance at the same time that some regulations, particularly the Volcker rule, have discouraged banks from holding and making markets in such debt. High-risk corporate debt (the sum of high-yield bonds and leveraged loans) grew rapidly in 2013 and 2014, although growth has declined sharply since then.

However, firms also are holding high levels of liquid assets, so net leverage is not elevated. Firms have also lengthened their maturity profiles, and interest coverage ratios are high. Greenwood and Hanson’s measure of the share of high-yield debt in overall issuance is at a relatively low level. And this debt is now held more by unlevered investors. Overall, I do not see leveraged finance markets as posing undue financial stability risks. And if risk-taking does not threaten financial stability, it is not the Fed’s job to stop people from losing (or making) money.

As I said, a mixed picture. Low interest rates have encouraged risk-taking and higher leverage in some sectors and have weighed on profitability in others, but the areas where there are signs of excess are isolated.