The recently published RBA Bulletin included an article “Recent Developments in the ATM Industry”. The article shows that the number of ATMs in Australia is very high relative to population, thanks to significant growth in third party fee for service machines. Now that the banks have announced they will not charge for foreign withdrawals, the RBA says third party players – like owners of petrol stations and convenience stores may see a decline in income, and that overall declines in transaction volumes are likely to reduce the number of machines available, especially in regional areas. That said, many independently owned ATMs are in convenience locations not serviced by bank ATMs (such as pubs and clubs) and so they may be shielded somewhat from this competitive pressure. But many consumers will end up paying even higher fees to use these machines, which may be the only options for some.

The ATM industry in Australia is undergoing a number of changes. Use of ATMs has been declining as people use cash less often for their transactions, though the number of ATMs remains at a high level. The total amount spent on ATM fees has fallen, and is likely to decline further as a result of recent decisions by a number of banks to remove their ATM direct charges. This article discusses the implications of these changes for the competitive landscape and the future size and structure of the industry.

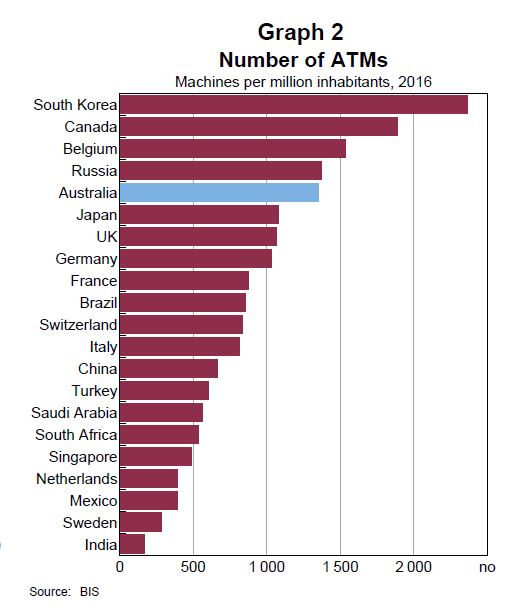

By international standards, we have a large number of ATMs per capita (though not corrected for geographic size).

As at September 2017, there were 32 275 ATMs, only slightly below the peak of nearly 32 900 in December 2016. This represents over 1 300 ATMs per million inhabitant.

The share of the national ATM fleet owned by independent deployers has been rising over the past decade. Independent deployers operate standalone ATM networks that are not affiliated with any financial institution and which are often focused on convenience locations like petrol stations and licensed venues. They rely on the revenue generated by charging fees on all transactions, irrespective of the cardholder’s financial institution, to support their networks.

As at June 2017, 57 per cent of ATMs in Australia were independently owned, up from 55 per cent in mid 2015 and 49 per cent in 2010. The remaining 43 per cent were owned by financial institutions. The increase in the independent deployers’ share reflects strong growth in their ATMs, while the number of bank-owned ATMs has declined over the past few years.

A small number of ATMs that carry financial institutions’ branding but are owned and operated by an independent deployer are recorded in data for independent deployers; other similar arrangements may be recorded under financial institutions. (b) In late 2016, DC Payments acquired First Data’s Cashcard ATM business. (c) NAB, Cuscal and Bank of Queensland, along with a number of other smaller financial institutions, are part of the rediATM network, which allows customers of member institutions to access about 3 000 ATMs (as at June 2017) within that network on a fee-free basis. From August 2017, Suncorp also joined the rediATM network. (d) In November 2017, Stargroup was placed in administration after it was unable to complete a restructure of its debt.

There has been significant consolidation in the independent deployer market over recent years. Cardtronics, an independent deployer, had the largest fleet in Australia in June at nearly 10 500 ATMs, which is around one-third of all ATMs. Cardtronics is part of a US-based group that is also the largest deployer of ATMs globally. It entered the Australian market around the start of 2017 when it acquired DC Payments, which was the largest domestic independent deployer at the time. DC Payments had itself acquired a number of smaller independent networks over earlier years, including First Data’s Cashcard ATM business in late 2016. Other large independent deployers, such as Banktech and Next Payments, have also expanded their ATM fleets since 2015, partly through acquisitions.

Despite the increase in the share of independently owned ATMs, most Australian cardholders have had access to large networks of fee-free ATMs provided by their financial institutions. As at June 2017, three of the four major banks each had fleets of at least several thousand ATMs; NAB had the smallest fleet among the majors, but it is also part of the rediATM network, which means its customers had access to about 3 000 ATMs in that network on a fee-free basis.

A number of the banks, including all the majors, have recently removed the ATM withdrawal fees they used to charge non-customers. This means Australian cardholders can now generally access cash free of charge at around 11 000 financial institution ATMs across the country, which is a significant increase in access to fee-free ATM services.

However, following the removal of withdrawal fees by various banks, the distribution has changed significantly: there is now no charge for foreign withdrawals at around one-third of ATMs, whereas most of these ATMs had previously charged $2.00. But Independent deployer ATMs have the greatest variation in ATM fees; as at June this year, their withdrawal fees ranged from zero to $8.00, though most were around $2.50 to $3.00.

With the removal of withdrawal fees providing a much larger network of fee-free ATMs, it will now be even easier for cardholders to avoid paying fees. As a result, those ATM deployers that continue to charge withdrawal fees – particularly independent deployers, who typically charge the highest average fees – may face additional competitive pressure, especially where they have ATMs in close proximity to fee-free bank ATMs. That said, many independently owned ATMs are in convenience locations not serviced by bank ATMs (such as pubs and clubs) and so they may be shielded somewhat from this competitive pressure.

For those banks that eliminated their withdrawal fees, the direct reduction in their revenue will be relatively small, especially given the decline in ATM use over recent years. In particular, based on the Bank’s survey, it is estimated that withdrawal fees paid at ATMs owned by the major banks in 2016/17 totalled around $50 million. As noted earlier, the bulk of ATM fees has been paid at independent deployer ATMs rather than bank-owned ATMs.

Given that cardholders can now effectively use most bank ATMs on a fee-free basis, it is likely that having a large ATM fleet will be viewed as less of a source of competitive advantage to banks than it was in the past. With ATM use declining rapidly and the costs of ATM deployment continuing to rise, the removal of ATM fees may strengthen the case for deployers to reduce the size of their ATM fleets. Having multiple bank ATMs side-by-side or in close proximity (as can often be seen in shopping centres, for example) will make less economic sense now that all or most of those ATMs are fee-free.

Fleet rationalisation could occur in a number of ways. Some banks (and possibly independent deployers) might look to better optimise their own fleets by removing ATMs in low-density or low-use areas. Banks may look to pool part or all of their fleets with other banks under generically branded, shared service or ‘utility’ ATM models as a way to improve efficiency, while still maintaining adequate access for cardholders.

A pooled network may enable the participants to remove ATMs that are co-located or in close proximity, which would reduce costs and help them sustain, and possibly grow, their joint network coverage. Indeed, before the recent announcements on direct charges, some banks had been in discussions about pooling their ATM fleets into a shared utility.

Facing similar downward trends in cash and ATM use, a number of other countries, particularly in northern Europe, have successfully implemented or are considering shared ATM models. For example, bank ATMs in Finland were outsourced to a single operator in the mid 1990s, while Sweden’s five largest banks adopted a utility model earlier this decade. The large Dutch banks are currently looking to set up a joint ATM network to help ensure the continued wide availability of ATMs in the Netherlands even as cash use is decreasing.

While it is too early to assess the full impact of the recent announcements by the major banks, it is likely that they will focus attention on the growing disparity between the number of ATMs in Australia and the demand for ATM services.

Some consolidation seems likely, and may even be desirable for the efficiency and sustainability of the ATM network, though it will be important that adequate access to ATM services is maintained, particularly for people in remote or regional locations, where access to alternative banking services is often limited.