One of the critical issues which is hardly discussed in the media is that fact that many savers have funds in accounts which are paying very low rates of interest, when in fact there are better deals available. This little guilty secret allows banks to pump up their margins, offer highly attractive rates to capture new customers then milk them down stream.

Paying lower interest rates to longstanding customers is a long-running pricing strategy used by firms around the world, and gets almost NO coverage. Its a blatant example of “price discrimination” which occurs when providers offer different prices to different customers that have the same costs to serve but different willingness to pay.

But now the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has released a discussion paper on the problem, which we also see here in Australia. They believe this is unlikely to change without further intervention. They propose a solution which we think might be worth looking at here too. So today I am going to look through their report, and discuss the issue in depth.

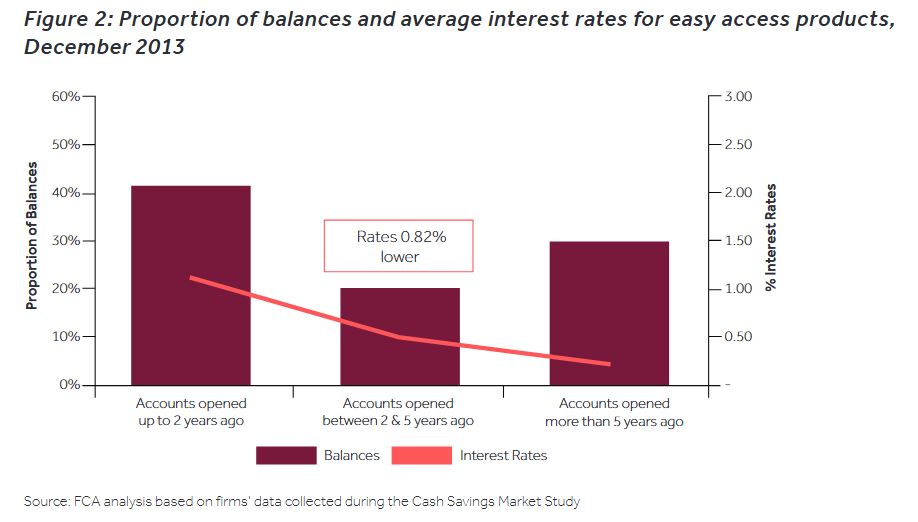

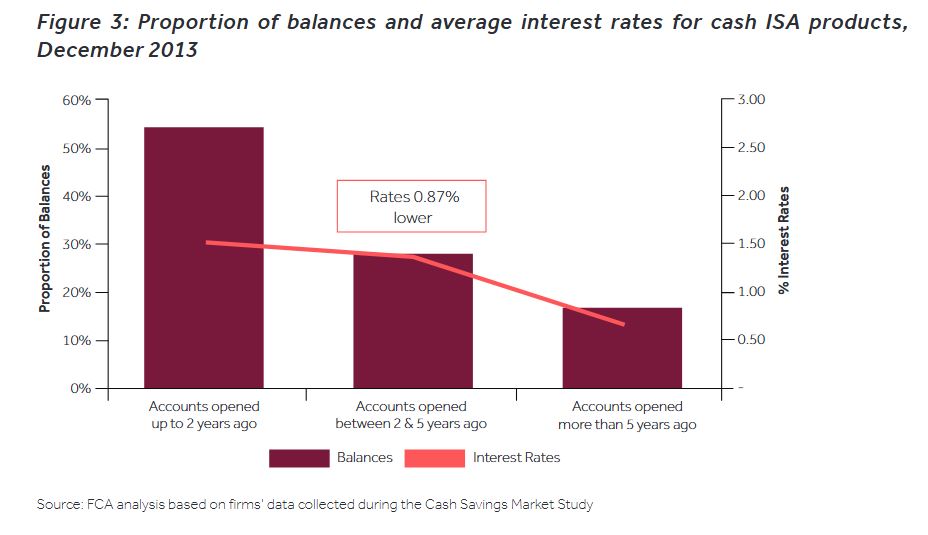

Many savers (yes there are still some with money in the bank despite the debt bomb), have their hard earned funds sitting in low interest paying accounts. Their research shows that 33% of the £354bn easy access savings account balances in savings accounts in the UK have been in accounts for more than 5 years, and that on average longstanding customers received on average 0.82% less than accounts opened more recently. A similar trend is also reported in the £108bn investment savings account, where again longstanding customers received on average 0.87% lower.

They call out the high level of consumer inertia in the cash savings market, with only 9% of consumers switching in the last 3 years. Their research also highlights that providers have multiple easy access products, leading to confusion for consumers, and large personal account providers have a competitive advantage over smaller providers.

They call out the high level of consumer inertia in the cash savings market, with only 9% of consumers switching in the last 3 years. Their research also highlights that providers have multiple easy access products, leading to confusion for consumers, and large personal account providers have a competitive advantage over smaller providers.

So they has initiated a discussion about what should be done in the UK to improve outcomes for customers.

So they has initiated a discussion about what should be done in the UK to improve outcomes for customers.

They say that consumers are put off switching by the expected hassle; large, well-established personal current account providers are able to attract most savings balances despite offering lower rates; and there is a lack of product transparency.

In fact this is the latest in a series of interventions which the FCA has been look at since 2015. They initially trialed

- A switching box: provided to customers periodically, setting out the potential financial gains from switching. This would prompt customers to consider their choice of account and provider.

- RSF: a simple ‘tear-off’ form and pre-paid envelope which would enable a customer to switch to a better paying account offered by their existing provider more easily (internal switching).

Neither worked that well, though the second, a simple tear-off form was a little more effective.

They also tried what they called a sunlight remedy for 18 months in 2015-16. In this trial, they asked firms to provide data on the lowest possible rate that customers could earn across all their easy access savings accounts and easy access cash ISAs. This was split into on-sale and off-sale accounts and branch and non-branch accounts. They released the data over 12 months, via publications. However, they found that the trial did not have a clear, measurable impact on providers’ rate setting strategies. There may be several reasons for this, including that the rates published did not always accurately reflect the rate being paid to most customers.

In the current paper they describe some of the other options they considered, including a complete price discrimination ban on easy access cash savings products. This would involve firms being required to offer single interest rates for all easy access cash savings accounts and easy access cash ISAs, irrespective of the length of time the account has been open.

Banning price discrimination would address the harm against longstanding customers. Under this approach, providers would be unable to offer different interest rates based on age of account. Longstanding customers would have the most to gain from this approach as they are likely to see an increase to their interest rates. Furthermore, customers would not have to take any action to be put on to the same rate as new customers.

It would also increase transparency as providers would be unable to obfuscate prices by making interest rates for all customers clear. This would make it easier for customers to understand and compare their interest rate. It would therefore be beneficial for competition as it would make it easier for customers to shop around for a potentially better value product with an alternative provider.

It may be beneficial for smaller providers with smaller back-books as it would not affect them as much as providers with larger back-books. Smaller providers would therefore be able to continue to offer higher rates than large providers, attracting customers.

This would make it easier for small firms to attract new balances and thus expand. The increased transparency adds to this effect as customers would be able to compare rates more easily and understand how different providers treat their customers.

However, the FCA says that although they have not performed any detailed modelling of this potential remedy, they believe that the unintended consequences of this approach could be significant and may outweigh the intended benefits. First, retail deposits make up a vital part of providers’ funding strategies, with 87% of funding generated by customer deposits (either current accounts or savings accounts).

This approach is, therefore, likely to have an adverse impact on funding models. It would significantly decrease flexibility and reduce providers’ ability to alter their pricing strategies to manage their funding requirements, ie by either shedding or attracting deposits. They

consider that this could lead to significant unintended consequences. They, therefore, believe that a less restrictive option would be more proportionate relative to the harm. Secondly, the impacts may be offset by significantly reducing front-book interest rates across the board, particularly for larger providers. This is because providers may find it too costly to increase interest rates on all back-book accounts. This may reduce the benefits of shopping around for more active customers who wish to remain with a larger provider.If the customer knows they are getting the best internal rate, there may be less of an incentive to shop around at all. If fewer customers shopped around, this may have the effect of further entrenching the power of the incumbents.

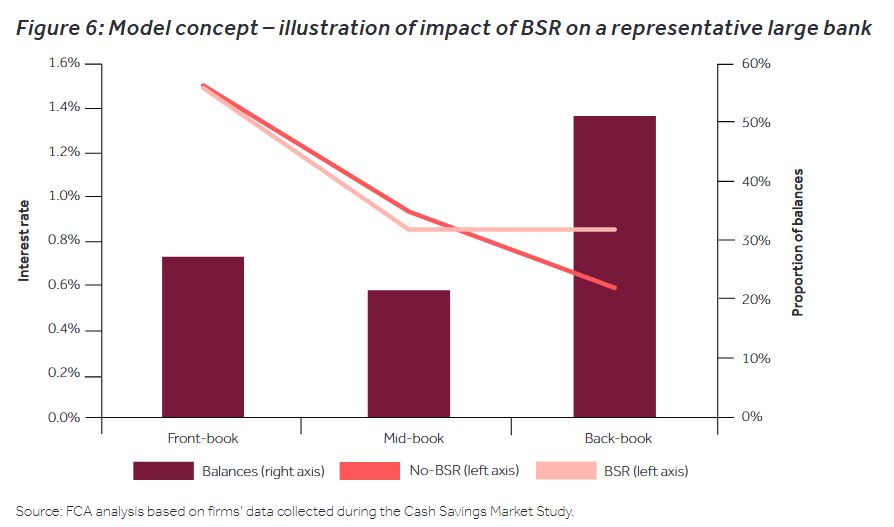

So, instead, they suggesting the introduction of a basic-savings-rate (BSR).

The BSR would involve providers applying single interest rates (BSRs), respectively, to all easy access cash savings accounts and to all easy access cash ISAs which have been open for a set period of time (for example, 12 months). Individual providers could decide the level of their BSR, and would be able to vary it. Providers would remain able to offer different interest rates to customers in the period before the BSR applies (the front-book).

The BSR option that they have modelled is based on providers having broadly 3 groups of customers:

- front-book customers who opened their accounts less than 1 year earlier

- mid-book customers who opened their accounts between 1 and 2.5 years earlier

- back-book customers who opened their accounts over 2.5 years earlier

They suggest that consumers could gain £300m per year – (actually a range of £150m – £480m)

This is a net transfer from firms to customers, taking into account the ‘waterbed effect’ between the different customer groups. They envisage that a BSR could apply to an account after it has been open for a specified length of time. Providers would retain the freedom to offer a full range of easy access products to front-book customers (ie on accounts before the BSR applies) and would also be free to offer the BSR to front-book customers.

This is a net transfer from firms to customers, taking into account the ‘waterbed effect’ between the different customer groups. They envisage that a BSR could apply to an account after it has been open for a specified length of time. Providers would retain the freedom to offer a full range of easy access products to front-book customers (ie on accounts before the BSR applies) and would also be free to offer the BSR to front-book customers.

They envisage that a BSR could apply to all banks and building societies that offer easy access cash savings accounts and easy access cash ISAs. Credit unions were excluded from the scope of the CSMS as most products they offer could not be substituted for others. Most credit unions offer a dividend rather than an advertised interest rate on their savings. This dividend can depend on how much profit the credit union has made in the year.

They say it would be important for the BSR to be communicated effectively to consumers. This would ensure that consumers are aware of the changes to their interest rate on their savings account and prompt them to consider their choice of savings account and firm; in doing so, they may increase competitive pressure. In addition to providers’ current obligations on the communication of interest rate changes, to provide clarity to consumers before they open their account, providers could:

- display their BSR prominently on their webpage, clearly stating that this is their ‘Basic Savings Rate’ and that it is comparable

- include the BSR in summary boxes for easy access accounts; they could make the interest rate that would apply after 12 months clear and include a projection of the balance of the account when the BSR applies based on a £1,000 account balance.If a BSR were to be proposed, the FCA’s current view is that providers should communicate the change to existing customers when they first implement the BSR. Sunlight remedy linked to a BSRAs a development of the sunlight remedy trialled in 2015-16, they could introduce a sunlight remedy linked to the BSR. They could ask providers to report their BSRs to the FCA to be published on the FCA website biannually. The aim of this would be to bring to light firms’ strategies towards their longstanding customers. They would expect this to:

- be reported by the media as an indicator of how firms treat longstanding customers, exerting reputational pressure on firms to change their behaviour

- increase back-book rate transparency, removing a switching barrier by making it easier for customers to understand if they are getting a good dealThey believe that publishing BSRs on the FCA webpage would be more successful than the sunlight trial, given that the BSRs would be directly comparable across firms. they, therefore, believe this would be more likely to have an effect on providers’ rate-setting strategy.

I think its time we had a debate in Australia about the same issue, because data from my surveys highlights that many savers are not getting the best returns they could. So far as I can see ASIC has not even looked at the problem, more shame on them. Another case where regulators here are asleep, and customers are being ripped off as a result – does that sound familiar?