Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank Of England, and the Chair of the Financial Stability Board – the global peak body worrying about the stability of the financial system – gave a speech in New York – “True Finance – Ten years after the financial crisis“. Within the speech he explained the Three Lies of Finance, and today we discuss them in the Australian context.

He pointed out that we seem destined to have a financial crisis every decade – 10 years ago it was the GFC, 20 years ago the Asian crisis and three decades back the Latin American debt crisis. So, are we due another?

Well, he argues that much has been done to secure the financial system since the GFC, but there are risks that three lies may once again lead to a crisis.

The first lie of finance he says is “This Time Is Different”.

This misconception is usually the product of an initial success, with early progress gradually building into a blind faith in a new era of effortless prosperity. He cites the example of the battles against the high and unstable inflation, rising unemployment and volatile growth of the 1970s and 1980s. Stagflationary threats were tamed by new regimes for monetary stability that were both democratically accountable and highly effective. This included, Clear remits. Parliamentary accountability. Sound governance. Independent, transparent and effective policy-making. The so called Great Moderation.

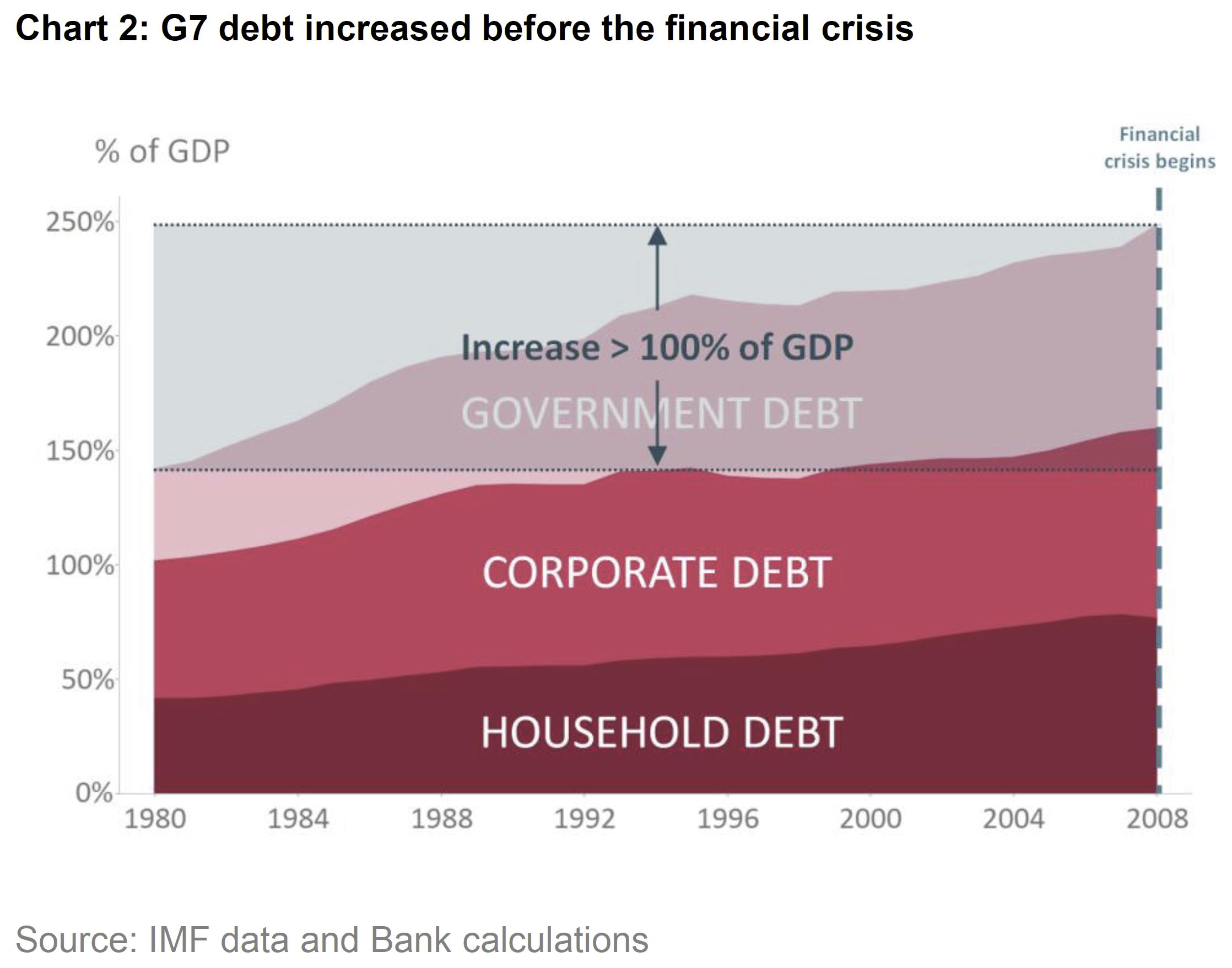

But these innovations did not deliver lasting macroeconomic stability. Far from it. Price stability was no guarantee of financial stability. An initially healthy focus would become a dangerous distraction. Against the serene backdrop of the so-called Great Moderation, a storm was brewing as total non-financial debt in the G7 rose by the size of its GDP.

But these innovations did not deliver lasting macroeconomic stability. Far from it. Price stability was no guarantee of financial stability. An initially healthy focus would become a dangerous distraction. Against the serene backdrop of the so-called Great Moderation, a storm was brewing as total non-financial debt in the G7 rose by the size of its GDP.

Several factors drove this debt super-cycle including demographics and the stagnation of middle-class real wages (itself the product of technology and globalisation). In the US, households had to borrow to increase consumption. “Let them eat cake” became “let them eat credit”.

Several factors drove this debt super-cycle including demographics and the stagnation of middle-class real wages (itself the product of technology and globalisation). In the US, households had to borrow to increase consumption. “Let them eat cake” became “let them eat credit”.

Financial innovation made it easier to do so. And the ready supply of foreign capital made it cheaper.

Most importantly – and this is the lie – complacency among individuals and institutions, fed by a long period of macroeconomic stability and rising asset prices, made this remorseless borrowing seem sensible.

When the crisis broke, policymakers quickly dropped the received wisdoms of the Great Moderation and scrambled to re-learn the lessons of the Great Depression. Minsky became mainstream.

And in Australia, I still hear many saying our finance sector, and housing sector is different – thanks to high migration, export growth, and great government policy. None of this makes us different, the big lie is many think we are, until we are proved not to be. In fact, today, still many seem unconcerned by the debt bomb we have created. Yet to me, this is one of our greatest challenges.

The second lie is that “Markets Always Clear”. There was a deep-seated faith in markets that lay beneath the new era thinking of the Great Moderation. Many argued that you must allow the market free reign, because finance can regulate and correct itself spontaneously, and so authorities retreated from their regulatory and supervisory responsibilities. Does this sound familiar – ASIC and APRA?

Carney says there are two dangerous consequences. First, if markets always clear, they can be assumed to be in equilibrium— or said differently “to be always right”. If markets are efficient, then bubbles can neither be identified nor can their potential causes be addressed. Such thinking dominated the practical indifference to the clear housing and credit booms.

Second, if markets always clear, they should possess a natural stability. Evidence to the contrary must be the product of either market distortions or incomplete markets. Much of financial innovation springs from the logic that the solution to market failures is to build new markets on old ones. He calls this progress through infinite regress.

So we saw light touch regulatory agenda in quest for a perfect real world of complete markets. But in reality, people are irrational, economies are imperfect, and nature itself is unknowable. When such imperfections exist, adding markets can sometimes make things worse.

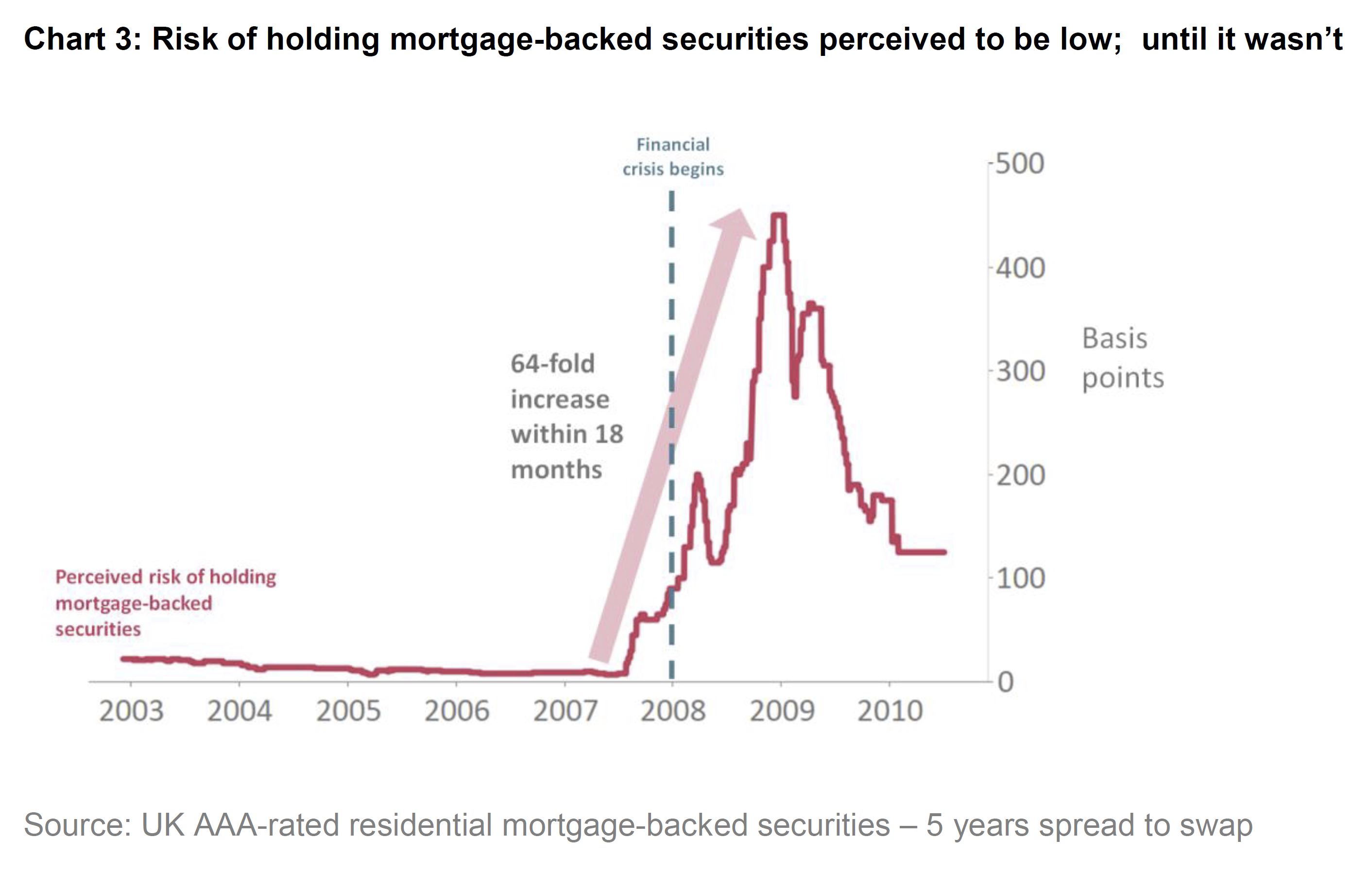

Take synthetic credit derivatives, which were supposed to complete a market in default risk and thereby improve the pricing and allocation of capital. Financial alchemy appeared to have distributed risk, parcelling it up and allocating it to those who wanted most to bear it.

However, the pre-crisis system had only spread risk, contingently and opaquely, in ways that ended up increasing it. Once the crisis began, risk quickly concentrated on the balance sheets of intermediaries that were themselves capital constrained. And with the fates of borrowers and lenders tied together via hyper-globalised banks and markets, problems at the core spread violently to the periphery.

However, the pre-crisis system had only spread risk, contingently and opaquely, in ways that ended up increasing it. Once the crisis began, risk quickly concentrated on the balance sheets of intermediaries that were themselves capital constrained. And with the fates of borrowers and lenders tied together via hyper-globalised banks and markets, problems at the core spread violently to the periphery.

A truth of finance is that the riskiness of an asset depends on who owns it. When markets don’t clear, agents may be surprised to find what they own and for how long. When those surprises are – or are thought to be – widespread, panic ensues. The swings in sentiment that result – pessimism one moment, exuberance the next – do not reflect nature’s odds, but our own assessments of them, inevitably distorted by Keynes’ optimistic “animal spirits” and his cynical “beauty contests”.

These are dynamics that can afflict not just sophisticated investors, but mortgage lenders and homebuyers, especially during a “new era”. If house prices can only go up, it is possible to borrow large multiples and pay off future obligations with the capital gains that will follow. Such so called “rational” behaviour fuelled the credit binge that ultimately led to the global crisis.

In the end, belief that “markets are always right” meant that policymakers didn’t play their proper roles moderating those tendencies in pursuit of the collective good. The right regulation is essential, as the Royal Commission into Financial Services Misconduct has been highlighting. And breaking up the too big to fail structures is essential. And yet many commentators are STILL arguing for a hands off approach to let the markets rip. This is a lie.

The third lie is “Markets Are Moral”

This argues that markets are always moral, and have a social licence, but the crisis showed that if left unattended, markets can be prone to excess and abuse. In financial markets, means and ends can be conflated too easily. Value can become abstract and relative. And the pull of the crowd can overwhelm the integrity of the individual.

We saw this in the Royal Commission where greed drove unacceptable behaviours, with profit overriding the interest of customers and community expectations, leading to excess returns at any costs, never mind the social damage. Worse those in charge of these financial firms, and the regulators were all singing from the same hymn sheet. Australia Inc. has paid dear for this lie.

Carney says episodes of misconduct – such as the Libor and FX scandals – called into question the social licence that markets need to innovate and grow. Rather than being professional and open, markets became informal and clubby. Rather than competing on merit, participants colluded online. Rather than everyone taking responsibility for their actions, few were held to account.

The crisis reminded us that real markets don’t just happen; they depend on the quality of market infrastructure for their effectiveness, resilience and fairness. Robust market infrastructure is a public good in constant danger of under-provision, not least because the best markets innovate continually. This risk can only be overcome if all market actors, public and private, recognise their responsibilities for the system as a whole.

By undervaluing the importance of hard and soft infrastructure to the functioning of real markets, light touch regulation led directly to the financial crisis. We need the right regulation, we cannot leave it to the market, to self-police.

Now this is very important as we contemplate the deflating housing sector. As a nation we have been allured by the three lies.

But let’s be clear. Our property and finance sector is not unique or different. The market is subject to a host of vested interests from Government, to construction, to finance, all worshipping the free market that exploits unfairly. And we absolutely need the right – and better checks and balances to ensure fairness and equity. Self-regulation and light touch regulation are not going to do it.

With respect to “this time is different”, the speech also refers to the importance of ending too big to fail.

“An anti-fragile system requires ending Too Big to Fail. …. But higher capital and liquidity requirements are necessary but not sufficient. Banks must also be able to fail without systemic consequences.”

I share your belief that bank deposits should be insulated from the risk of bail-in, but the speech notes the importance of having sufficient loss absorbing debt to allow a bank to be recapitalised should its equity prove inadequate.