The Federal Reserve’s widely anticipated rate rise is a reminder that while the US has learned from its housing market crash, our political leaders have created a record bubble of mortgage debt by shying away from reform.

When Fed chair Janet Yellen announced Thursday morning (Australian time) the fed-funds rate had risen to a new target range of 0.75 to 1 per cent, it caused barely a stir in markets. The New York Stock Exchange rose 0.8 per cent, as the Fed signalled future rate rises are likely to arrive sooner than previously expected.

These days the Fed telegraphs each move so effectively that markets no longer ask ‘will they move or not?’, but more ‘does that move reflect what’s really happening in the economy?’

Yes, with its years of super low rates, the Fed did set the scene for the 2009 housing collapse that hit global markets like a tsunami. But its three rate rises since the GFC have been spot on – late enough to avoid choking the recovery, but early enough to prevent inflation getting out of hand.

At a press conference Ms Yellen said the Fed is pushing rates back towards “normal” levels because the US economy has returned to reasonable health – growing at a “moderate pace”.

Meanwhile, Australia’s rates remain at historic lows. So what are we doing wrong?

The biggest reason we’re not seeing US-style growth is, gallingly, entirely self-imposed. Our political leaders have skewed the economy heavily towards real estate investing.

The vast sums of capital tied up in housing could be establishing new businesses, or backing the expansion of existing ones. Instead, we’re a nation hypnotised by capital gains that thinks buying and selling the same houses back and forth is a productive industry.

It all began in 1999, when treasurer Peter Costello cut capital gains tax to a rate well below the personal tax rates of middle- and upper-middle class Australians. It was one of the most economically harmful policies ever dreamt up in Canberra.

It did not take the nation’s accountants long to point out to clients that investing in a property, negatively gearing it for a few years, and then banking the capital gain at the new rate would slash the investor’s tax bills.

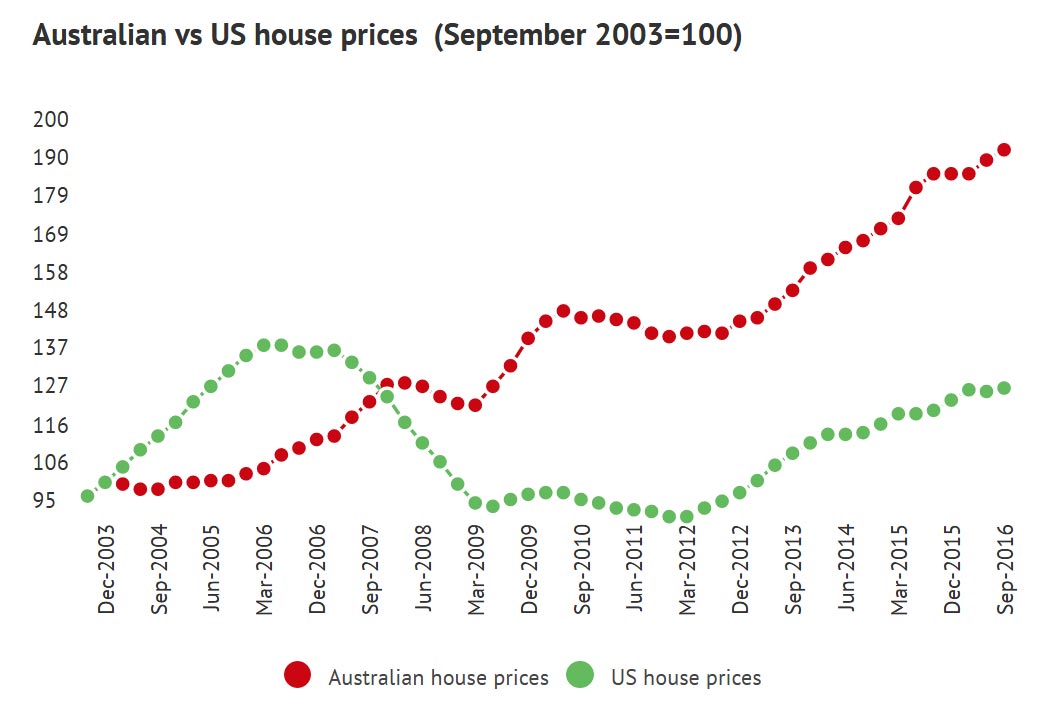

During the same period, the US was experiencing a credit bubble for different reasons – super low rates, plus the advent of sub-prime mortgages.

When the early ‘sub-prime’ phase of the GFC finally began to be felt, US house prices tumbled. And when the sub-prime crisis worked its way through the banking system, global stock markets crashed too.

Whereas the US learned from this and started rebuilding, we arrested our correction and did everything possible to keep the credit bubble growing.

As the share market tanked in 2009, Australian policy makers decided that the sacred cow of house prices must be protected at all costs. The 2009 first home buyer’s grant kickstarted that defence, and was topped up by most state governments too.

Even though the Rudd government’s own tax review – the Henry Tax Review – had recommended reining in negative gearing and the capital gains tax discount, all that was ignored.

The tax lurks stayed, gleefully maintained by the Abbott and Turnbull governments, and the RBA joined in by cutting interest rates that blew the credit bubble larger still.

The lack of action by politicians has pushed responsibility for reining in the bubble to the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, which imposed a fairly weak ‘speed limit’ on credit growth two years ago.

And now the RBA itself is threatening to put more “sand in the gears” of the credit machine.

It’s all too little, too late.

Australia, having ‘escaped’ the house price collapse that swept through so many nations in 2009, is now stuck in a self-imposed debt bubble.