When we published our sensitivity analysis on mortgaged households, which shows that more than 20% were on the edge financially speaking even at current low rates, a number of people asked why this was so, given the assumed affordability buffers and other underwriting safeguards.

Well, apart from the obvious issues of static incomes, rising costs of living, and potentially higher interest rates ahead, many mortgaged households also have other debts to repay. So today we run through some of our survey results looking at these other household debts. And it is not pretty.

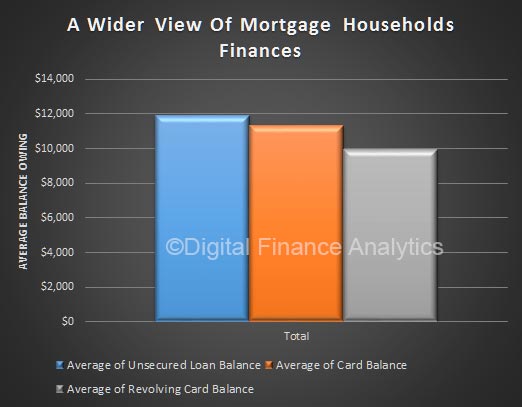

To start, here is the average balances for mortgaged households, looking at their use of unsecured credit (e.g. personal loans, store cards etc) and credit cards. In the case of credit cards, we show two balances, first the current outstanding balance, and second the average revolving (hard core) debt outstanding. Households with debts, on average and on top of the mortgage have $12,000 in unsecured loans, $11,000 in card debt, of which $10,000 is revolving. These can cost as much to service each month as the mortgage repayment!

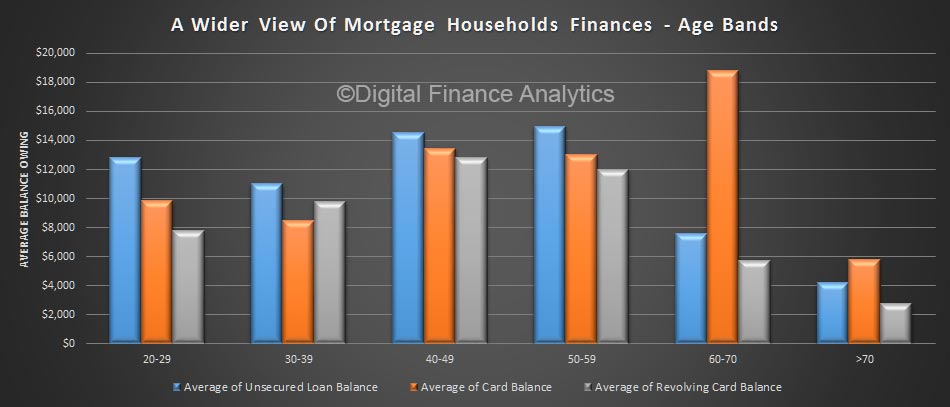

We can slice and dice the households, using some of our custom SQL views. For example, here are the average balances by household age bands. Households between 40 and 59 have the larger loan and revolving balances, though interestingly, those 60-70 have the largest card balances.

We can slice and dice the households, using some of our custom SQL views. For example, here are the average balances by household age bands. Households between 40 and 59 have the larger loan and revolving balances, though interestingly, those 60-70 have the largest card balances.

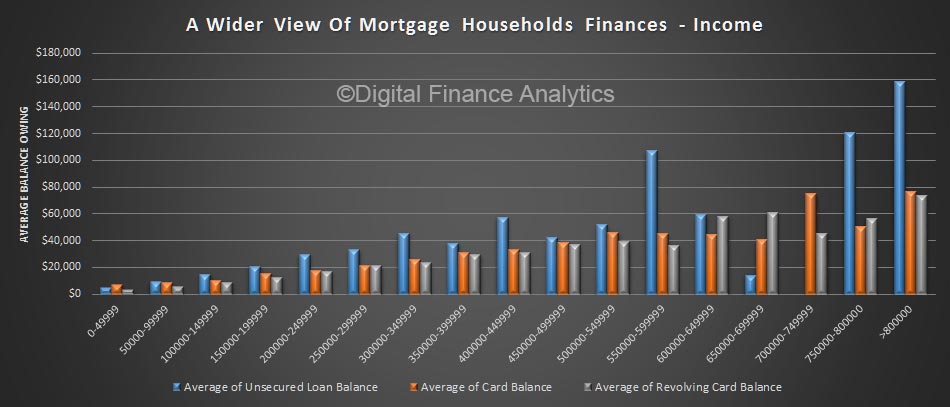

As incomes rise, debt levels also rise, so some of the debt is owned by households with more ability to repay. However, remember the larger number of households are in the first three bands, where debt is still rife.

As incomes rise, debt levels also rise, so some of the debt is owned by households with more ability to repay. However, remember the larger number of households are in the first three bands, where debt is still rife.

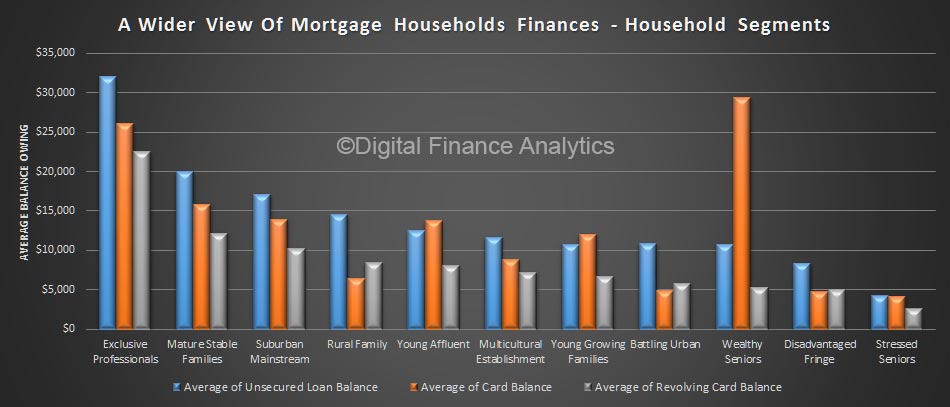

We can examine this debt by our master household segments. Once again, more affluent households have larger debts, but young growing families have on average close to $20,000 in debt, including some on revolving cards (where interest is charged at a high rate).

We can examine this debt by our master household segments. Once again, more affluent households have larger debts, but young growing families have on average close to $20,000 in debt, including some on revolving cards (where interest is charged at a high rate).

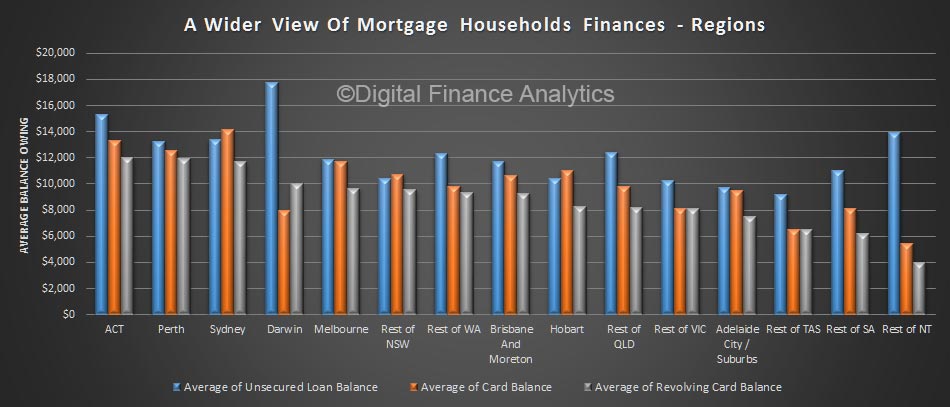

We can examine the data across our regions. Urban centres, including ACT, Greater Sydney and Melbourne have the highest debt levels. Many of these households also hold the largest mortgages.

We can examine the data across our regions. Urban centres, including ACT, Greater Sydney and Melbourne have the highest debt levels. Many of these households also hold the largest mortgages.

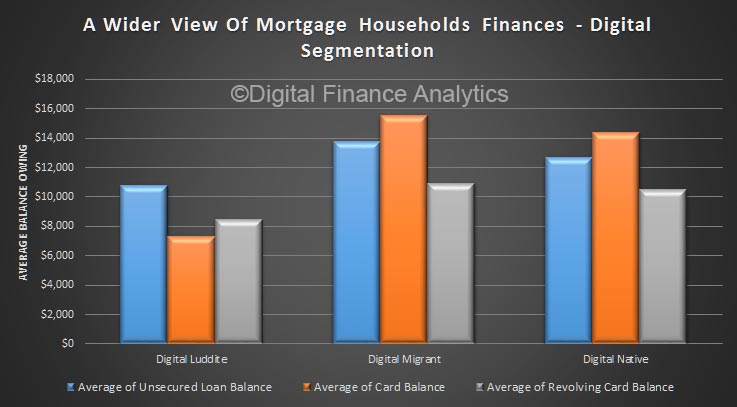

Finally, it is interesting to note that from a digital behaviour standpoint, those younger households who are online most of the time and prefer to use digital channels (Natives) borrow more than Luddites (those who prefer not to go online, but the larger debts are held by households who have migrated online. These Migrants are progressively using online channels more than ever. You can read more about our channel use inour report The Quiet Revolution.

Finally, it is interesting to note that from a digital behaviour standpoint, those younger households who are online most of the time and prefer to use digital channels (Natives) borrow more than Luddites (those who prefer not to go online, but the larger debts are held by households who have migrated online. These Migrants are progressively using online channels more than ever. You can read more about our channel use inour report The Quiet Revolution.

So, to sum up. Many households have large mortgages AND other debts, including credit cards and personal loans. This entire portfolio of debt must be considered when looking at their sensitivity to rising rates, and when comparing static incomes with rising debt repayments. Just looking at the mortgage gives only part of the full picture.

So, to sum up. Many households have large mortgages AND other debts, including credit cards and personal loans. This entire portfolio of debt must be considered when looking at their sensitivity to rising rates, and when comparing static incomes with rising debt repayments. Just looking at the mortgage gives only part of the full picture.

Much of this debt would not exist when the bank made their mortgage underwriting decision. That point in time view however does not necessarily still hold true. Should ongoing affordability testing be required by the regulators?