The ANZ move to cut rates on some of its cards will stimulate more discussion on the economics of the credit card business. It may appear a bold move, but we are not so sure.

Actually all the the various bank and ABA initiatives are not necessarily going to help to rebuild trust in the banks. Like a running sore, the ongoing exposure may well reinforce current negative consumer perceptions. A point event like a specific review might actually draw the poison more effectively! And yes, there are major issues to address.

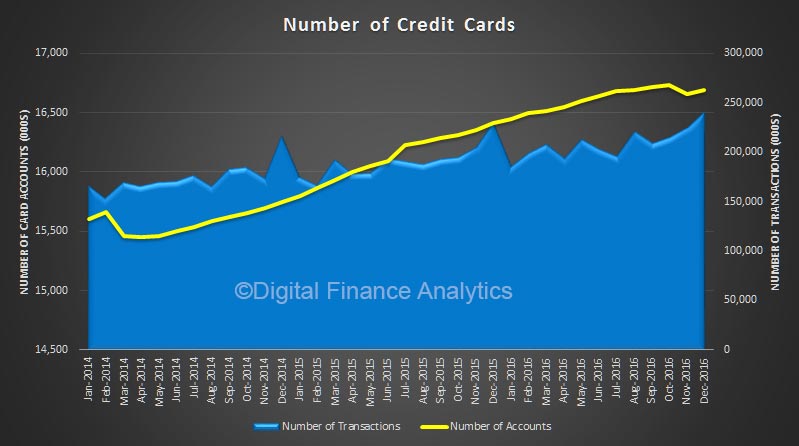

But, today we look at credit card economics. To do this we use the data provided by the RBA. They show the number of card accounts (not the same as card numbers because some accounts will have multiple cards on them) has been growing, to approach 16.7 million accounts. The number of transactions on these accounts are also growing, with 241m transactions to December 2016.

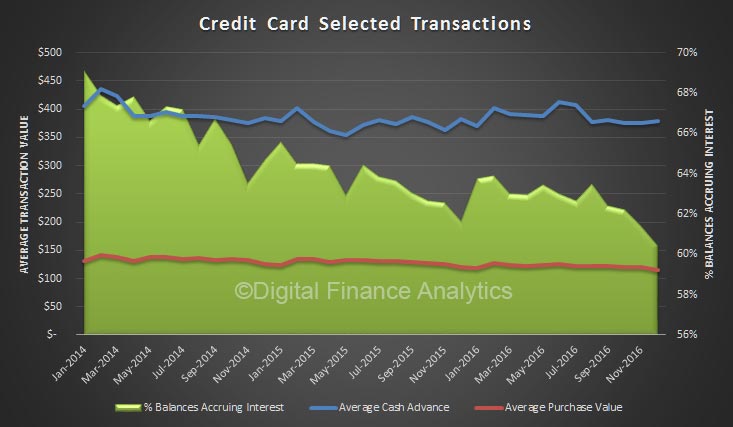

The average value of a transaction has remained relatively static, with the average purchase around $120 and the average cash withdrawal around $380. But significantly the proportion of account balances which are accruing interest is reducing, with around 40% of accounts being cleared off each month. Households who can clear their cards should do so to avoid interest costs.

The average value of a transaction has remained relatively static, with the average purchase around $120 and the average cash withdrawal around $380. But significantly the proportion of account balances which are accruing interest is reducing, with around 40% of accounts being cleared off each month. Households who can clear their cards should do so to avoid interest costs.

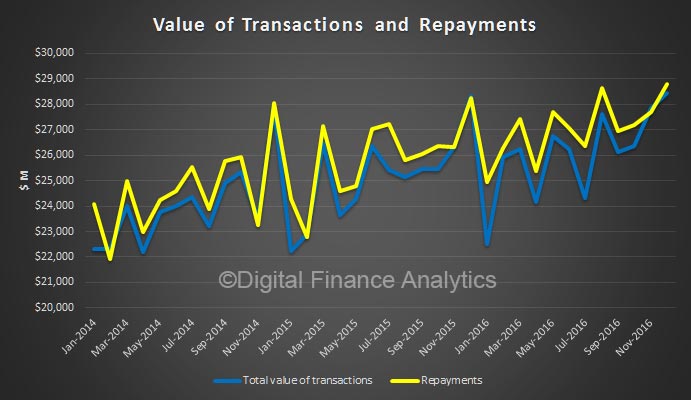

We see the monthly flows of new transactions and repayment match quite closely.

We see the monthly flows of new transactions and repayment match quite closely.

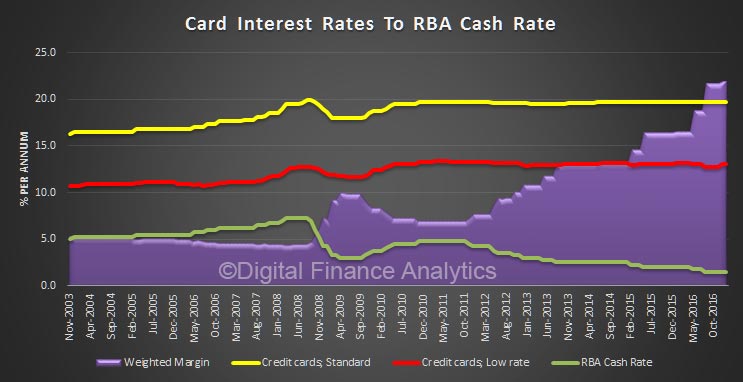

The 60% of balances which are revolving incur interest costs. The data shows despite cuts to the RBA cash rate, rates on both low rate and standard rate cards remain high, and indeed, some low rate cards have moved up recently. As a result the average interest margin between the cash rate and the charged rate is higher than it has ever been, on average close to 20%. This puts the ANZ 2% cut on some cards into perspective!

The 60% of balances which are revolving incur interest costs. The data shows despite cuts to the RBA cash rate, rates on both low rate and standard rate cards remain high, and indeed, some low rate cards have moved up recently. As a result the average interest margin between the cash rate and the charged rate is higher than it has ever been, on average close to 20%. This puts the ANZ 2% cut on some cards into perspective!

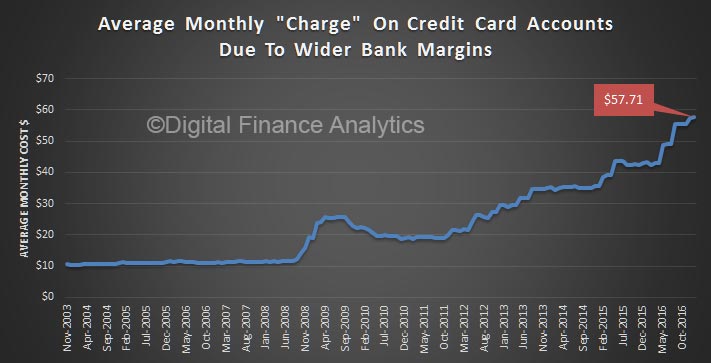

So, now we know the proportion of cards which are revolving, and the margin, we can estimate the real net cost to the average revolving card holder. We estimate the typical account will incur a monthly interest charge of $57 each month they revolve, compared with $10 in 2003. In fact we see a stable cost until 2008, since when it has climbed substantially. This is worth about $80m a month to the banks at the current margins.

So, now we know the proportion of cards which are revolving, and the margin, we can estimate the real net cost to the average revolving card holder. We estimate the typical account will incur a monthly interest charge of $57 each month they revolve, compared with $10 in 2003. In fact we see a stable cost until 2008, since when it has climbed substantially. This is worth about $80m a month to the banks at the current margins.

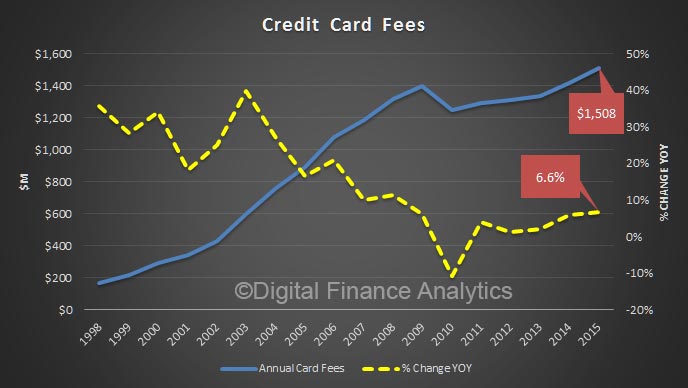

To broaden the analysis, banks have also been slugging households with higher credit card fees. Again the RBA says, fees rose 6.6% in 2015 (last year of available data) and they took $1.5 billion in card fees in that year. In the past four years, card fees have risen significantly faster than inflation.

To broaden the analysis, banks have also been slugging households with higher credit card fees. Again the RBA says, fees rose 6.6% in 2015 (last year of available data) and they took $1.5 billion in card fees in that year. In the past four years, card fees have risen significantly faster than inflation.

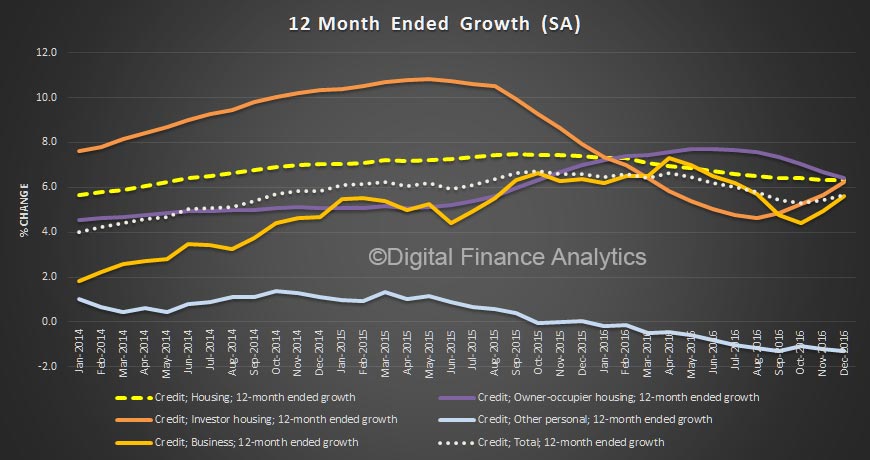

Finally, overall personal credit growth has fallen in recent times, as mortgage borrowing roar ahead. This is consistent with our observation that more households are repaying their cards each month.

Finally, overall personal credit growth has fallen in recent times, as mortgage borrowing roar ahead. This is consistent with our observation that more households are repaying their cards each month.

Later we will look at the broader economics of cards, taking account of loyalty schemes and merchant fees. Meantime you can read our earlier analysis of credit card economics by segment. But from a margin view, 2% is hardly a generous concession.