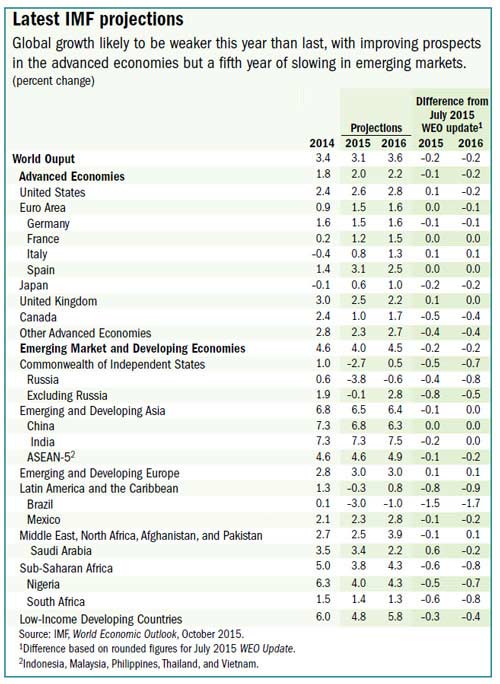

The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook (WEO) makes 230 pages of sober reading. Global growth for 2015 is projected at 3.1 percent, 0.3 percentage point lower than in 2014, and 0.2 percentage point below the forecasts in the July 2015 World Economic Outlook (WEO) Update.

They list a litany of potential down-side risks to growth, including China’s economic transformation—away from export- and investment-led growth and manufacturing, in favor of a greater focus on consumption and services; the related fall in commodity prices; and the impending increase in U.S. interest rates, which can have global repercussions and add to current uncertainties. They foresee lower global growth compared to last year, with only modest pickup in advanced economies and a slowing in emerging markets, primarily reflecting weakness in some large emerging economies and oil-exporting countries.

Whilst global real GDP grew at 3.4 percent last year, and is forecast to grow at only 3.1 percent this year, growth is expected to rebound to 3.6 percent next year. However, we note that expected future growth is consistently being moved into the future.

“Six years after the world economy emerged from its broadest and deepest postwar recession, the holy grail of robust and synchronized global expansion remains elusive,” said Maurice Obstfeld, the IMF Economic Counsellor and Director of the Research Department. “Despite considerable differences in country-specific outlooks, the new forecasts mark down expected near-term growth marginally but nearly across the board. Moreover, downside risks to the world economy appear more pronounced than they did just a few months ago”.

In this global environment, with the risk of low growth for a long time, the WEO underlines the need for policymakers to raise actual and potential growth.

Recovery in advanced economies on course

Growth in advanced economies is projected to increase modestly to 2 percent this year and 2.2 percent next. This year’s pickup reflects primarily a strengthening of the modest recovery in the euro area and a return to positive growth in Japan, supported by declining oil prices, accommodative monetary policy, and improved financial conditions, and in some cases, currency depreciation.

While growth is expected to increase in 2016, especially in North America, medium-term prospects remain subdued, reflecting a combination of lower investment, unfavorable demographics, and weak productivity growth.

Slower growth in emerging and developing economies

Growth prospects in emerging markets and developing economies vary across countries and regions. But the outlook in 2015 is generally weakening, with growth for these economies as a group projected to decline from 4.6 percent in 2014 to 4.0 percent in 2015.

The fifth straight year of slowing growth reflects a combination of factors: weaker growth in oil exporters, a slowdown in China with less reliance on commodity-intensive investment, adjustment in the aftermath of credit and investment booms, and a weaker outlook for exporters of other commodities, including in Latin America, following declines in their export prices. In addition, geopolitical tensions and domestic strife in a number of countries remain high, with immense economic and social costs.

External conditions are becoming more difficult for most emerging economies. The prospect of rising U.S. interest rates and a stronger dollar has already contributed to higher financing costs for some borrowers, including emerging and developing economies. And while the growth slowdown in China is so far in line with forecasts, its cross-border repercussions appear larger than previously envisaged, including through weaker commodity prices and reduced imports.

The projected rebound in growth in emerging market and developing economies in 2016 therefore reflects not a general recovery, but mostly a less deep recession or a partial normalization of conditions in countries in economic distress in 2015 (including Brazil, Russia, and some countries in Latin America and in the Middle East), spillovers from the stronger pickup in activity in advanced economies, and the easing of sanctions on the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Growth in low-income developing economies is expected to slow to 4.8 percent in 2015, from 6 percent in 2014, in large part due to weak commodity prices and the prospect of tighter global financial conditions. Some countries (e.g., Kyrgyz Republic, Mozambique) have been running large current account deficits, benefiting from easy access to foreign savings and abundant foreign direct investment, especially in resource-rich countries, and hence are particularly vulnerable to external financial shocks.

Downside risks more significant

Given the distribution of risks to the near-term outlook, global growth is more likely to fall short of expectations than to surprise on the upside. The WEO report outlines important shifts that could stall global recovery. These include:

• Lower oil and other commodity prices, which although benefiting commodity importers, complicate the outlook for commodity exporters, some of whom already face strained initial conditions (e.g., Russia, Venezuela, Nigeria).

• A sharper-than-expected slowdown in China, if the expected rebalancing toward a more market-based and consumption-driven growth proves more challenging than expected.

• Disruptive asset price shifts and a further increase in financial market volatility could involve a reversal of capital flows in emerging market economies. Further, renewed concerns about China’s growth potential, Greece’s future in the euro area, the impact of sharply lower oil prices, and contagion effects could be sparks for market volatility.

• A further appreciation of the U.S. dollar could pose balance sheet and funding risks for dollar debtors, especially in some emerging market economies, where foreign–currency corporate debt has increased substantially over the past few years.

• Increased geopolitical tensions in Ukraine, the Middle East, or parts of Africa could take a toll on confidence.

Policy upgrades to avoid low-growth traps

The report underscores that raising actual and potential output must remain the policy priority. This will require a combination of demand support and structural reforms.

In advanced economies, accommodative monetary policy continues to be essential, alongside macroprudential tools to contain financial sector risks, the report notes. On the fiscal side, countries with room for fiscal stimulus, such as Germany, should use it to boost public investment, especially in quality infrastructure.

Structural reforms are, of course, country specific. But the main planks include measures to strengthen labor force participation, facilitate labor market adjustment, tackle legacy debt overhang, and lower barriers to entry in product markets, especially in services.

Many emerging markets have increased their resilience to external shocks. Thanks to increased exchange rate flexibility, higher foreign exchange reserves, increased reliance on foreign direct investment flows and domestic-currency external financing, and generally stronger policy frameworks, many countries are now in a stronger position to manage heightened volatility.

Nevertheless, in a more complex external environment, emerging market and developing economies face a difficult trade-off between supporting demand amid slowing actual and potential growth and reducing vulnerabilities. The scope for policy easing varies considerably across countries, depending on macroeconomic conditions and sensitivity to commodity price shocks, as well as external, financial, and fiscal vulnerabilities.

For example, commodity exporters have to adjust to lower commodities-related revenue—gradually if fiscal buffers were built during the commodity boom, and more rapidly otherwise. In commodity-exporting countries with flexible exchange rate regimes, currency depreciation can help offset the demand impact of terms-of-trade losses. Yet, sharp exchange rate changes can also exacerbate vulnerabilities associated with high corporate leverage and foreign currency exposure. Therefore, exchange rate policy should not lose sight of financial stability considerations. At the same time, countries need to diversify their economies. Targeted structural reforms to raise productivity and remove bottlenecks to production can help countries to diversify their export bases.

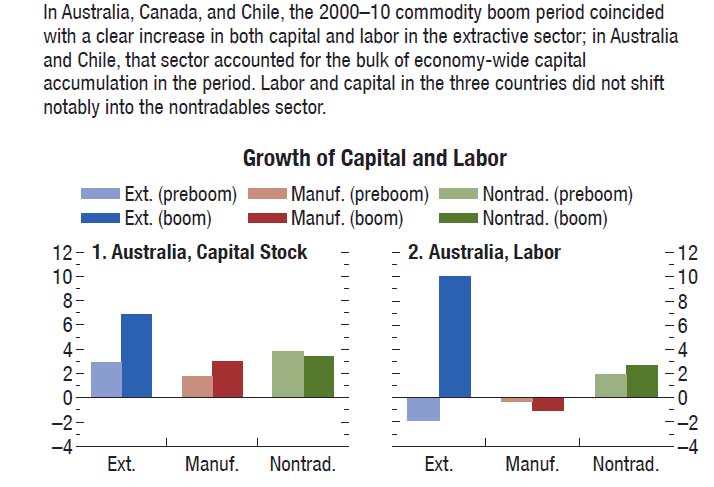

In their analysis of commodity trade-exposed countries, like Australia, they highlight the fact that investment in the resources sector did not translate into broader economic development.