According to Moody’s, U.S. housing is in the midst of a minor slump.

Housing starts fell 5.3% to 1.2 million annualized units in September, close to our forecast of 1.195 million but weaker than the consensus of 1.22 million. Revisions were mixed. Starts are now shown to be 1.268 million annualized units in August (previously 1.282 million) and 1.184 million in July (previously (1.177 million).

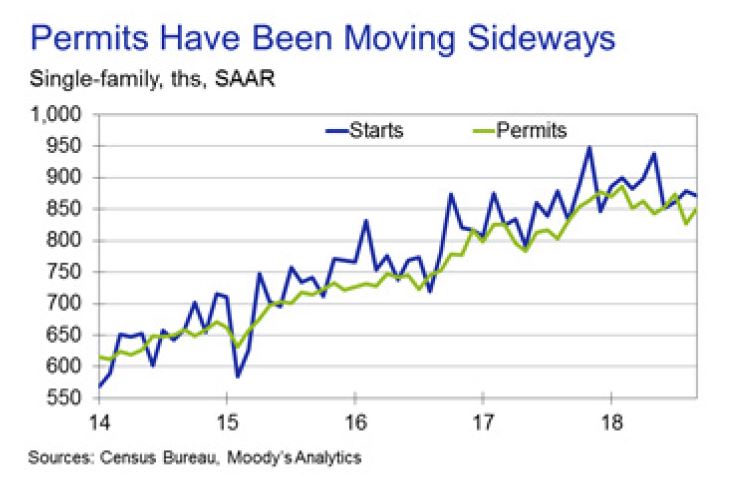

Turning back to September, single-family starts fell 0.9% to 871,000 annualized units. Multifamily starts dropped 15.2% to 330,000 annualized units. It’s likely that Hurricane Florence hurt housing starts in September. To assess the potential impact, we look at the not seasonally adjusted starts in the South, which fell 17.3% in September, the most for any September since 2007. Total permits fell 0.6% to 1.241 million annualized units, weaker than we had anticipated. The good news is that single-family permits rose 2.9%, reversing some of the 5.3% decline in August. The trend in single-family permits has weakened, and starts are still running ahead of permits, which isn’t overly favorable. For the sixth consecutive month, multifamily permits dropped, falling 7.6% in September. However, permits are still running ahead of multifamily starts, suggesting a pickup in starts in the next couple of months.

Housing starts lowered our high-frequency GDP model’s estimate of real residential investment in the third quarter. The impact on GDP wasn’t significant. We are playing a little catch-up and Wednesday’s run of our high-frequency GDP model also incorporates the monthly Treasury budget and industrial production for September. Federal government spending is coming in stronger than previously thought, which boosted our estimate of third quarter GDP while September industrial production had no effect. Overall, third quarter GDP is on track to rise 3.3% at an annualized rate.

September U.S. retail sales disappointed, but the details were solid. Nominal retail sales rose 0.1%, well short of both our and consensus expectations. A decline in sales at gasoline stations and large drop in restaurants weighed on growth in total retail sales. Odds are that Hurricane Florence hurt spending at restaurants, consistent with past hurricanes. Our forecast had penciled in a decline in restaurants, but gasoline was a little surprising. Building material store sales slipped in September, but there should be a hurricane boost in October. Overall, Florence was a net negative for retail sales in September and there is little evidence of a boost from sales of the new iPhone.

The key for GDP is control retail sales, or total excluding autos, building materials, gasoline and restaurants. Control retail sales rose 0.5% in September but they were revised lower in each of the prior two months. Overall, control retail sales were up 4.8% at an annualized rate in the third quarter. September control retail sales suggest that real consumption likely rose 0.4%, which lowered our highfrequency GDP model’s estimate of real spending in the third quarter from 3.7% to 3.5%. This is still a solid quarter for consumer spending.

This week we also updated our cost estimates for both Hurricane Florence and Hurricane Michael. For Michael, we have increased our estimate of property losses to between $17 billion and $20 billion. Lost output due to disruptions and power outages remains between $4 billion and $6 billion, leading to a total price tag of $21 billion to $26 billion. We lowered our cost estimate for Hurricane Florence to $30 billion to $38 billion.

On the policy front, the minutes of the September Federal Open Market Committee meeting didn’t contain many surprises, and the discussion about whether it’s appropriate to eventually have a more restrictive monetary policy was healthy. It was not as hawkish as recent comments by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who said that monetary policy is nowhere near neutral, which implied even more rate hikes. Therefore, the minutes don’t alter our subjective odds of a December rate hike (90%) nor our expectation that the Fed will raise rates once per quarter until they hit the terminal rate around 3.5%.

There is a strong consensus within the Fed that monetary policy will turn restrictive. Only a “couple of participants”—meaning two out of 16—would not favor going into restrictive territory absent clear signs of overheating and rising inflation. They are in the clear minority, but the discussion of restrictive monetary policy shouldn’t be surprising; this has been clearly evident in the Fed’s so-called dot plot, which since September 2017 has shown that the actual fed funds rate would eventually be set above the long-run equilibrium rate.

There were no other heated debates in the minutes. One interesting tidbit was the mention that there is little evidence to suggest that the upward pressure on the federal funds rate relative to the interest on excess reserves is attributable to any shortage of aggregate reserves in the banking system. We think the jury is still out on this, and this is important because the supply of reserves is going to be key in determining how much the Fed can reduce its balance sheet as well as the timing for the completion.