The normal line of argument has been that its central banks pumping liquidity into the financial markets which have led to falling real interest rates, and that they might indeed take them into negative territory. This is all to do with “secular stagnation” (reflecting poor productivity, globalisation, weak wages growth, and monetary policy intervention by central banks).

Last year the IMF in a working paper suggested that a cut of 4% or there abouts would be required to react to a financial crisis similar to the scale of the GFC. That would pull rates deeply negative, and of course so far (Sweden apart) no one has found a way back, as Japan and the Eurozone illustrates.

Many sovereign rates sit in negative territory, and there is an unprecedented $10 trillion in negative-yielding debt. This new interest rate climate has many observers wondering where the bottom truly lies.

Now, most economists are on a quest to return to a “stable positive rate”, eventually, considering negative rates to be there for am emergency, and temporary.

But a working paper from the Bank of England Eight centuries of global real interest rates, R-G, and the ‘suprasecular’ decline, 1311–2018 by Paul Schmelzing really puts the cat among the pigeons.

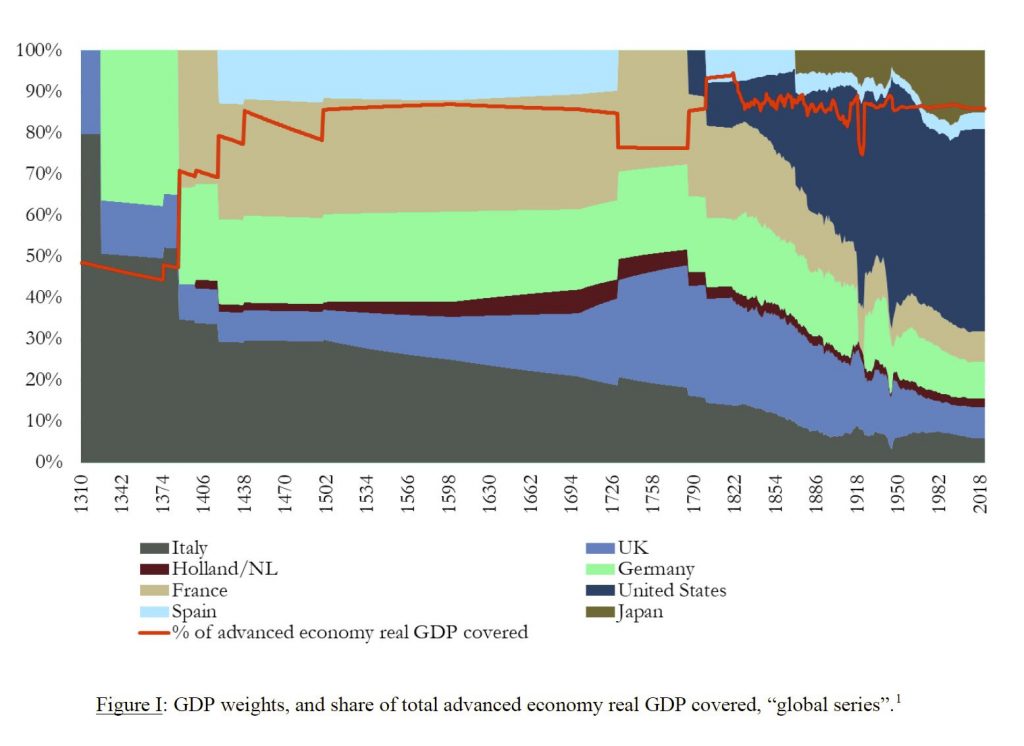

The paper creates a long term global series, weighted by GDP from 1310 to the present day. The series only includes yields which are not contracted short-term, which are not paid in-kind, which are not clearly of an involuntary nature, which are not intra-governmental, and which are made to executive political bodies. In other words, cash lending against annual payments in “chicken” and other commodities, or against leases for offices, against jewellery, land or other real estate with no known equivalent cash value are all excluded.

The GDP weights over time, and the share of advanced economy GDP covered by the series varies as history played out and empires rose and fell.

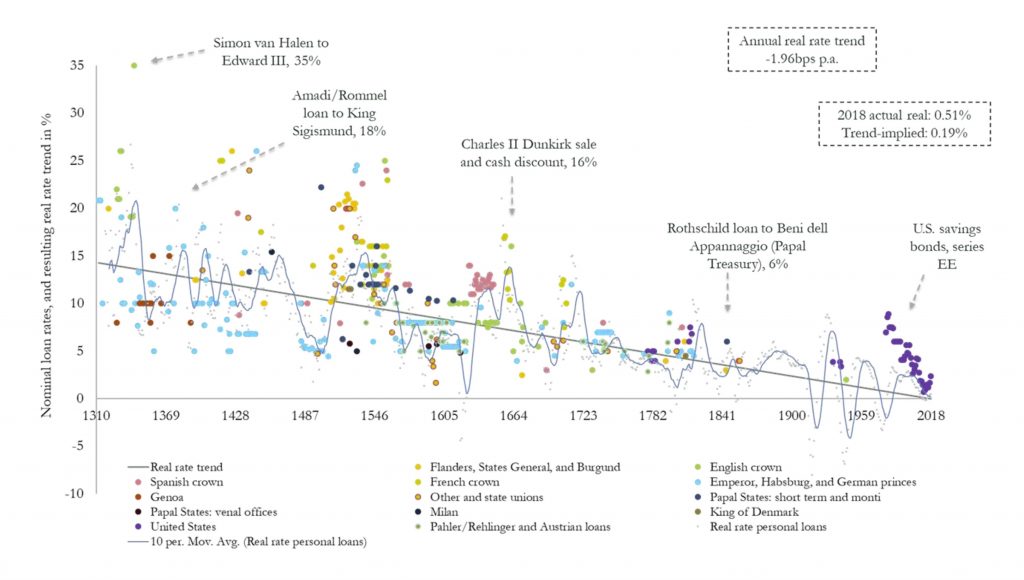

Data robustness is an issue, as the paper recognises as late medieval and early modern data can of course never be established with the same granularity as modern high-frequency statistics. One still has to rely on interpolations, deal with the peculiarities of early modern finance, and acknowledge that the permanency of wars, disasters, and destitution since medieval times may have irrecoverably destroyed a significant share of the evidence desired. However, the story is pretty clear.

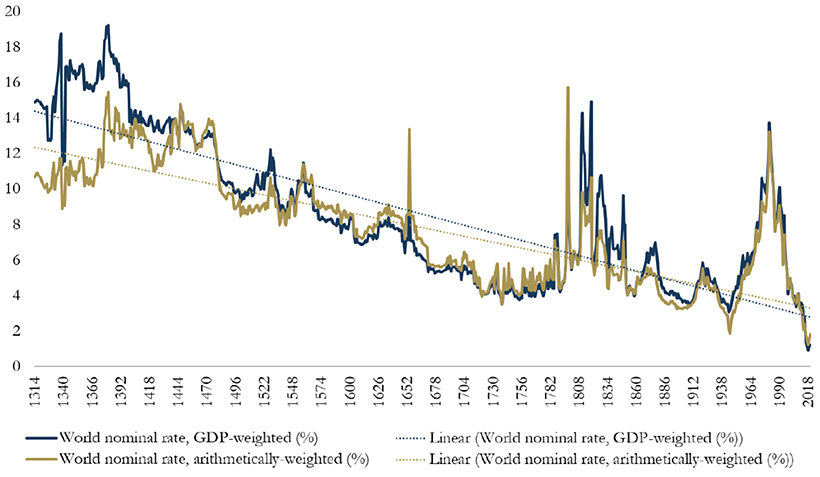

The data here suggests that the “historically implied” safe asset provider long-term real rate stands at 1.56% for the year 2018, which would imply that against the backdrop of inflation targets at 2%, nominal advanced economy rates may no longer rise sustainably above 3.5%. Whatever the precise dominant driver –simply extrapolating such long-term historical trends suggests that negative real rates will not just soon constitute a “new normal” – they will continue to fall constantly. By the late 2020s, global short-term real rates will have reached permanently negative territory. By the second half of this century, global long-term real rates will have followed.

The standard deviation of the real rate – its “volatility” – meanwhile, has shown similar properties over the last 500 years: fluctuations in benchmark real rates are steadily declining, implying that rate levels are set to become both lower, and stickier. But downward-trending absolute levels, and declining volatilities have persisted against a backdrop of a secularly growing importance of public and monetary balance sheets. This would suggest that expansionary monetary and fiscal policy responses designed to raise real interest rates from current levels may at best have a cyclical effect in the longer-term context.

According to the report, another trend has coincided with falling interest rates: declining bond yields. Since the 1300s, global nominal bonds yields have dropped from over 14% to around 2%.

He concludes:

I sought to suggest that a long-term reconstruction of real rate developments points towards key revisions concerning at least two major current debates directly based on – or deriving from – the narrative about long-term capital returns.

First, my new data showed that long-term real rates – be it in the form of private debt, non-marketable loans, or the global sovereign “safe asset” – should always have been expected to hit “zero bounds” around the time of the late 20th and early 21st century, if put into long-term historical context.

In fact, a meaningful – and growing – level of long-term real rates should have been expected to record negative levels. There is little unusual about the current low rate environment which the “secular stagnation” narrative attempts to display as an unusual aberration, linked to equally unusual trend-breaks in savings-investment balances, or productivity measures. To extent that such literature then posits particular policy remedies to address such alleged phenomena, it is found to be fully misleading: the trend fall in real rates has coincided with a steady long-run uptick in public fiscal activity; and it has persisted across a variety of monetary regimes: fiat- and non-fiat, with and without the existence of public monetary institutions.

Secondly, sovereign long-term real rates have been placed into context to other key components of “nonhuman wealth returns” over the (very) long run, including private debt, and real land returns, together with a suggestion that fixed income-linked wealth has historically assumed a meaningful share of private wealth. There is a very high probability, therefore, to suggest that “non-human wealth” returns have by no means been “virtually stable”, only if business investments have both shown an extreme increase in real returns, and an extreme increase in their total wealth share, could the framework be saved.

If compared to real income growth dynamics we equally detect a downward trend across all assets covered in the above discussion.

There is no reason, therefore, to expect rates to “plateau”, to suggest that “the global neutral rate may settle at around 1% over the medium to long run”, or to proclaim that “forecasts that the real rate will remain stuck at or below zero appear unwarranted” as some have suggested.

With regards to policy, very low real rates can be expected to become a permanent and protracted monetary policy problem – but my evidence still does not support those that see an eventual return to “normalized” levels however defined, who contemplate a “nadir” in global real rates in the 2020s): the long-term historical data suggests that, whatever the ultimate driver, or combination of drivers, the forces responsible have been indifferent to monetary or political regimes; they have kept exercising their pull on interest rate levels irrespective of the existence of central banks, (de jure) usury laws, or permanently higher public expenditures. They persisted in what amounted to early modern patrician plutocracies, as well as in modern democratic environments, in periods of low-level feudal Condottieri battles, and in those of professional, mechanized mass warfare.

In the end, then, it was the contemporaries of Jacques Coeur and Konrad von Weinsberg – not those in the financial centres of the 21st century – who had every reason to sound dire predictions about an “endless inegalitarian spiral”. And it was the Welser in early 16th century Nuremberg, or the Strozzi of Florence in the same period, who could have filled their business diaries with reports on the unprecedented “secular stagnation” environment of their days. That they did not do so serves not necessarily to illustrate their lack of economic-theoretical acumen: it should rather put doubt on the meaningfulness of some of today’s concepts.

So negative rates are coming and are here to stay!