The U.S. economy is humming along, but we believe that the economy will weaken and likely fall into recession sometime in 2020 as the boost from the fiscal stimulus fades. There is considerable uncertainty in the timing of the next recession, but the U.S. bond market increases our concerns about the economy in the next couple of years.

Since the mid-1960s, the yield curve, or the difference between the 10-year Treasury yield and three month yield, has been nearly perfect in predicting recessions. On average a recession occurs 15 months after the yield curve inverts. The shortest time between an inversion and a recession was eight months in the early 1970s. The longest was 20 months in the late 1960s. It has given only one false signal, in 1966, when a slowdown—but not an official recession—followed an inversion.

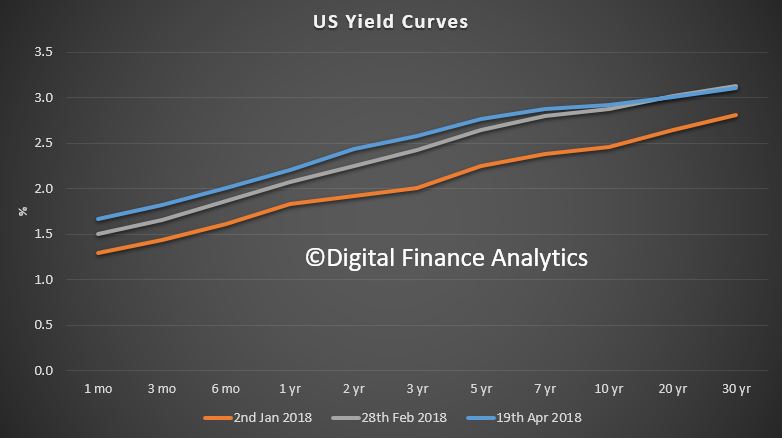

Assuming our forecast for the next downturn is correct, the yield curve should invert late this year or early next. Further flattening in the yield curve doesn’t alter our forecast for GDP growth this year, but it does pose some downside risk. As the yield curve flattens, it could weigh on the collective psyche, particularly among investors. Investors are a fickle bunch, and the further flattening in the yield curve could increase the odds of a sudden decline in stock prices, which if significant and persistent could have noticeable economic costs.

Knowing why the yield curve is flattening is important in assessing whether there should be concern about growth this year and early next. If it is because the lower long-term rates are fueled by concerns about U.S. growth, that would raise a red flag. This doesn’t appear to be the case now, because the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield has been hovering generally between 2.8% and 2.9% since the beginning of February and is up 40 basis points since the end of 2017. Therefore, the flattening in the yield curve is coming from the short end, which has put the focus on the Fed. But the central bank is only part of the story.

The flattening in the yield curve is less troubling for the economy in the very short run if it’s occurring because the economy is doing well and the Fed is raising short-term rates while the long-term rate continues to be depressed by the size of the Fed’s and other global central banks’ balance sheets.

It doesn’t appear that the dynamics for long-term rates will change significantly soon, so the next rate hike by the Fed, likely in June, will flatten the yield curve further. Therefore, the Fed will feel the heat for flattening the yield curve, potentially fanning concerns that it is headed for a policy mistake that will end this expansion.

However, the Fed isn’t the only reason that the yield curve is flattening. The Treasury Department has ramped up its issuance in anticipation of a higher deficit from last year’s tax overhaul and a two-year budget deal that will increase federal spending over the next two years. Over the past few months, Treasury net issuance of bills has spiked. Net issuance of bills in March was $211 billion following a net $111 billion in February. The increase in supply has driven short-term interest rates higher. In fact, prior to the Fed rate hike in March, the spread between the three-month Treasury bill and the fed funds rate was the widest over the past 15 years.

We see the odds rising that the yield curve inverts by the end of this year. This would increase the odds of a recession in the subsequent 12 months.