Yesterday we discussed a BIS working paper which suggested that Central Banker’s monetary policy have driven real interest rates lower, rather than demographics.

So, highlighting that modelling can prove anything, another working paper, this time from the Bank of England, comes down on the other side of the argument. The paper “Demographic trends and the real interest rate” says two-thirds of the fall in rates is attributable to demographic changes (in which case Central Bankers are responding, not leading rates lower). In fact, pressure towards even lower rates will continue to increase.

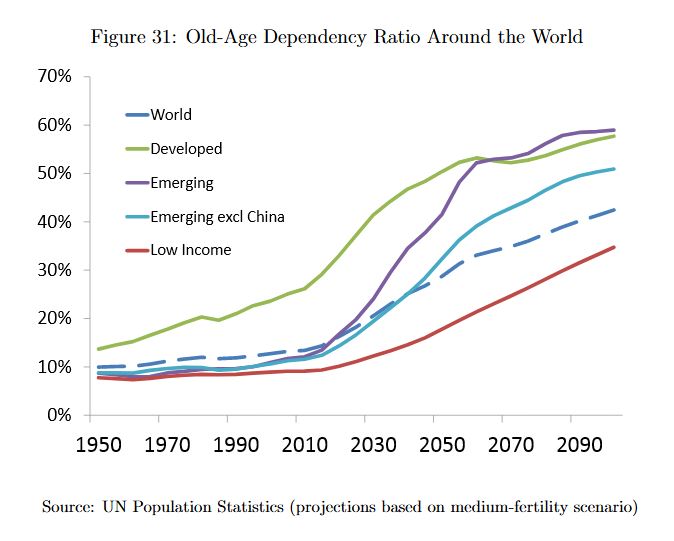

In the 2010s, advanced countries’ long-term real interest rates fell well below zero, to levels unprecedented in a period of peacetime and stable inflation. While the global financial crisis has played a part, this was the continuation of a downward trend that began at least two decades previously. At the same time, the population of advanced countries has continued to age, with life expectancy and the old-age dependency ratio reaching new highs. This paper quantifies the link between these two important trends. The advanced world is in the midst of a rapid and unprecedented ageing of its population, driven by a fall in birth rates and, more importantly, a rise in life expectancy.

When old-age pensions were first institutionalised in the early 20th century, the chance of reaching pensionable age, and residual life expectancy at that point, were relatively low. In contrast, the overwhelming majority of the population can now expect to retire for several decades. Households need to accumulate increased resources through their working lives to fund at least part of this. Furthermore, as household wealth tends to fall only slowly over retirement, more of the population will be at relatively high-wealth stages of life. This rise in the population’s effective propensity to hold wealth will in turn have profound effects on the financial system, its key relative price – the real interest rate – and the prices of other assets. To the extent that these trends are stronger or weaker in different countries, they will also give rise to international payments imbalances.

We use an overlapping generations model, calibrated to advanced country data, to assess the contribution of population ageing to the fall in real interest rates which the world has seen over the past three decades. We find that global demographic change can explain three-quarters of the 210bp fall in global real interest rates since 1980, and larger fractions of the rises in house prices and debt. Importantly, the sign of these effects will not reverse as the baby-boomer generation retires: demographic change is forecast to reduce rates by a further 37 bp by 2050.

Note: Staff Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Any views expressed are solely those of the author(s) and so cannot be taken to represent those of the Bank of England or to state Bank of England policy. This paper should therefore not be reported as representing the views of the Bank of England or members of the Monetary Policy Committee, Financial Policy Committee or Prudential Regulation Committee.