Interesting economic summary from Moody’s. They recognise the problem with household finances, and low income growth. They also suggest, mirroring the Reserve Bank NZ, that macroprudential policy might be loosened a little next year.

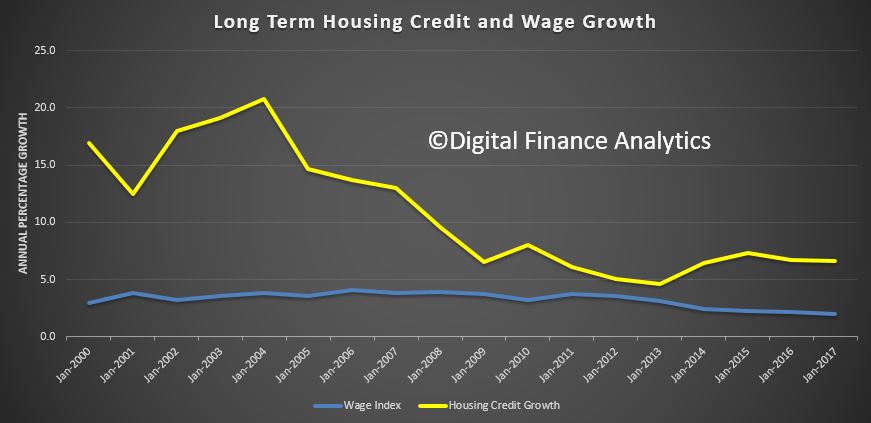

I have to say, given credit for housing is still running at three times income growth, and at very high debt levels, we are not convinced! I find it weird that there is a fixation among many on home price movements, yet the concentration and level of household debt (and the implications for the economy should rates rise), plays second fiddle.

Also, the NZ measures were significantly tighter, and the recent loosening only slight (and in the face of significant political measures introduced to tame the housing market). So we think lending controls should be tighter still in 2018.

Also, the NZ measures were significantly tighter, and the recent loosening only slight (and in the face of significant political measures introduced to tame the housing market). So we think lending controls should be tighter still in 2018.

It’s strange examining third quarter data when the fourth stanza has almost passed, but the Australian Bureau of Statistics isn’t known for timely national accounts data. Australia is the last major Asia-Pacific economy to release quarterly GDP numbers. Despite the tardiness, the national accounts gives valuable insight, especially on the investment front in the absence of a reliable monthly gauge.

Australia’s GDP growth hit 0.6% q/q in the September quarter following an upwardly revised 0.9% (previously reported as 0.8%) gain in the June stanza. Annual growth accelerated to 2.8% from the prior 1.8% gain. The annual growth figure is now hovering at potential, which we estimate is around 3%. However, momentum is overstated, given low base effects. In the September quarter of 2016, the Australian economy contracted by 0.5% q/q, only the fourth quarterly contraction in 25 years. This was driven by a sharp fall in investment alongside higher imports. During this period, annual growth slowed by 1.3 percentage point to 1.8%.

Private investment booms

Private investment was a bright spot in the third quarter because of a sharp rise in non-dwelling construction, which made the largest contribution to GDP growth at 0.9 percentage point.

Non-dwelling construction has often become a proxy for mining investment, and the third quarter gain is likely due to the installation of two liquefied natural gas platforms in Western Australia and the Northern Territory. LNG exports are expected to pick up late in the fourth quarter amid increased production capacity. The Wheatstone project began production earlier in October after a two-year construction phrase and

shipped its first export to Japan late in the month. Wheatstone is the sixth of eight projects included in a A$200 billion LNG construction boom that is now in its final stretch. Once the remaining two projects are finalized, Australia could topple Qatar as the world’s biggest LNG exporter. Australia has recently become the world’s second largest exporter of LNG.Public investment didn’t score as well in the third quarter, declining by 7.5% q/q. This is mainly payback after a boost in the June quarter from the acquisition of the Royal Adelaide Hospital from the private sector.

The housing market has cooled in 2017, and price growth is expected to keep decelerating through 2018; this will keep downward pressure on dwelling investment. For instance, dwelling price growth in Sydney was 5% y/y in November, well down from its double-digit growth in 2016 and earlier in 2017.

This is the result of the lagged impact of earlier macroprudential action that has included higher borrowing costs for homebuyers, especially investors or those taking out interest-only loans. The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority has also imposed limits on bank portfolio exposure to new mortgages.

Owner-occupied housing finance commitments tend to track house price growth and are a good gauge of the underlying pulse. Data released this week show October commitments rose just 0.3% m/m on a trend basis. Growth has slowed substantially from earlier in 2017.

An interesting tidbit we have observed in recent years: Housing regulation in New Zealand tends to lead Australia’s by at least a year. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand was on the front foot trying to cool certain heated housing pockets such as Auckland well before the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority introduced housing-targeted measures, even though both economies were experiencing strong price growth in some areas. Just recently, the RBNZ announced it had eased some macroprudential measures in light of softer house price growth. Now that Australia’s housing market has cooled, APRA may follow suit with minor reversals in the next year.Households missing in action

At first glance it was a relief that consumption made a positive contribution to GDP growth, but the details were less pleasing, as spending was concentrated on essential items while discretionary purchases suffered. We calculated that nondiscretionary items rose an average 0.6% over the quarter, and discretionary spending fell by 0.7%.

Of the nondiscretionary items, utility spending rose 1.4% q/q, food was up 1%, rent gained 0.6%, and insurance and financial services grew 1.3%. On the discretionary front, clothing spending fell 1% q/q, recreation and culture was down 0.6%, and spending at cafes and restaurants fell by 0.9%.

All told, softness in the consumer sector was largely masked by spending on nondiscretionary items. The monthly retail trade data do not capture nondiscretionary spending as thoroughly as the national accounts; over the third quarter retail volumes were up just 0.1% q/q.

We know from earlier testing that consumer sentiment does not have a causal relationship with retail spending, but incomes do. Sentiment is a symptom of weak income growth, rather than a forward indicator of spending behaviour. The Westpac consumer sentiment index fell to 99.7 in November, below the neutral 100 that indicates optimists equal pessimists. Overall, consumers have been downbeat through most of 2017, concerned about family finances and the economic outlook. At 2% y/y, income growth is hovering near a record low, so it’s little surprise households have pulled

back on discretionary purchases, while other costs such as utilities rose in the third quarter because of seasonal price hikes. The net household saving ratio rose to 3.2% in the third quarter, higher than the decade low of 3% in the June quarter, suggesting that consumers aren’t willing to keep dipping into their savings to fund discretionary purchases. It’s concerning that household consumption is weak, given that it constitutes 75% of GDP.Businesses are faring better than consumers at the moment. This is reflected in soaring private investment, lofty gains in company profits, and strong employment growth, particularly full-time, through 2017. Unfortunately, this has not yet flowed through to stronger income growth, and there are likely several factors at play. The first is cyclical: Low productivity is mooted as a reason for benign wages in the developed world. More Australia-specific is that underemployment has been very high in

Australia and the correlation with income growth is around -0.88. Underemployment has started to edge lower as full-time positions outpace part-time, and our baseline scenario is for the tighter labour market to yield stronger income growth by mid-2018. Although Australia’s Phillips curve has flattened in the past decade, there is still a reasonable relationship between unemployment and income growth.Some structural factors: The rise of the gig economy has contributed to the rise in casual employment. These positions are more flexible and more easily adapt to changing demand, but there’s no union representation, which can hurt wage bargaining. Also, as the positions are more flexible, there’s more acceptance that lower wages can be a consequence.

Another structural reason for low incomes could be the higher prevalence of offshoring roles. There’s no reliable industry- or economy-wide data measuring the extent of offshoring, but we know that it is an unrelenting phenomenon, given the disparity in operating costs between Australia and the developed world. Employers are not locally replacing jobs lost offshore, so they are not potentially driving up labour costs to secure the appropriate candidate.

All told, these structural factors suggest that national income growth is unlikely to enjoy a significant rebound but rather gradual and modest improvement in 2018.

How’s the fourth quarter tracking?

Our high-frequency GDP tracker suggests a 2.7% y/y expansion in the December quarter following the barrage of October activity data this week. Retail trade came in at a strong 0.5% m/m, although this was payback for sustained weakness through the third quarter, when retail turnover fell an average 0.3% m/m.

October foreign trade data weren’t inspiring, as merchandise exports fell by 2% m/m amid lower iron ore prices and, to a lesser extent, volumes. The iron ore spot price increased by 22% from its late-October slump to US$71.51 per metric tonne in early December. We expect this will enable iron ore export receipts to improve heading into 2018 as higher global prices are incorporated into contracts; usually the lag is short. It’s too early to determine whether volumes will be adversely affected by higher prices.

We maintain our view that monetary tightening is firmly off the table for at least another year as the central bank sits on the sidelines waiting for consumption to show meaningful signs of a pickup. Our expectation is that the Australian dollar will depreciate around an additional 3% against the U.S. dollar over the next six months, serving to encourage more consumption onshore and lift export competitiveness and helping core inflation return to and creep through the central bank’s 2% to 3%

target range.