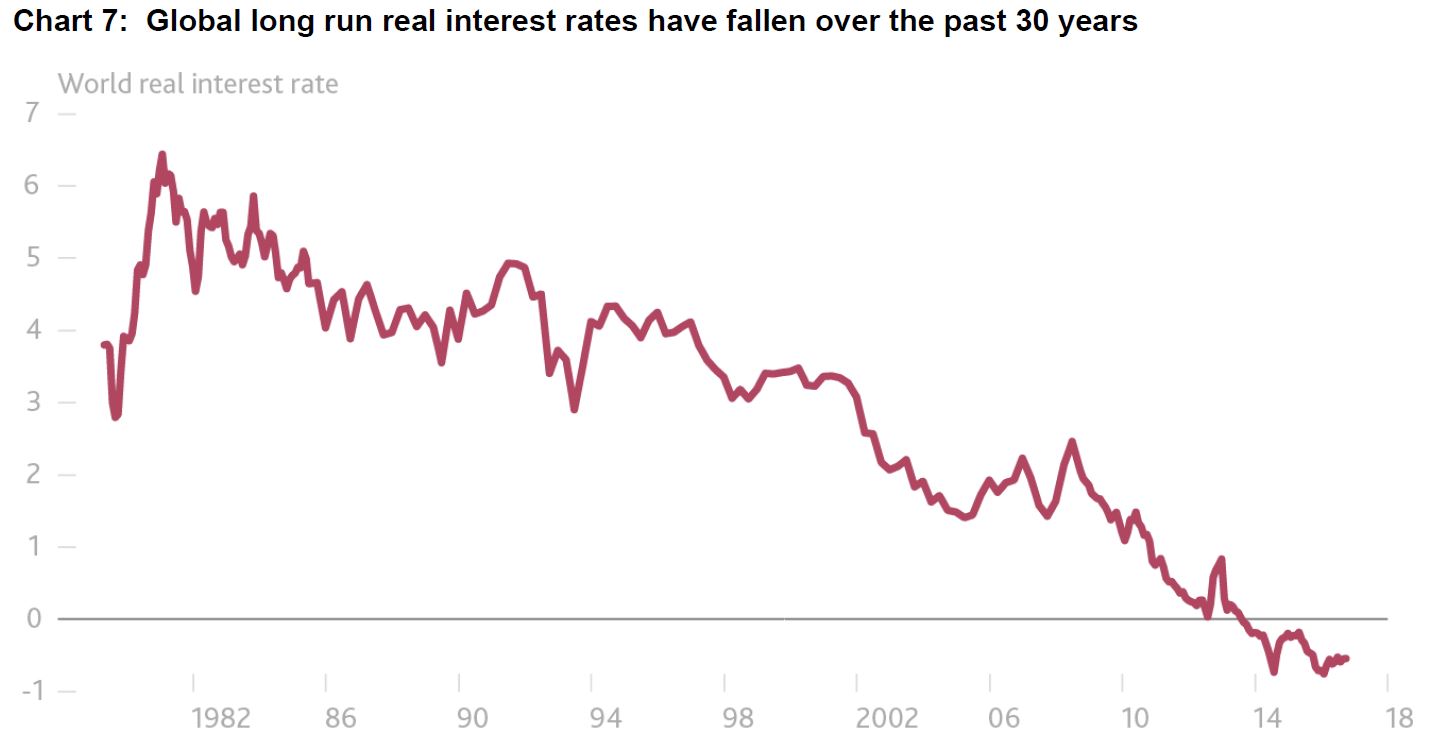

Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England gave a speech “[De]Globalisation and inflation“. One passage in particular is highly significant. He discussed the impact of globalisation on inflation, and suggests that there are likely to be further downward pressure on real world interest rates, partly thanks to changing demographics and the relative pools of global investment and global savings. The net result is more investors looking for returns, compared with investment pools – which explains the bidding up of asset prices (including property and shares) while returns to investors continue to fall. The point is, this is structural – and wont change anytime soon. Indeed, he suggests real world interest rates could go lower, with the flow on to inflation.

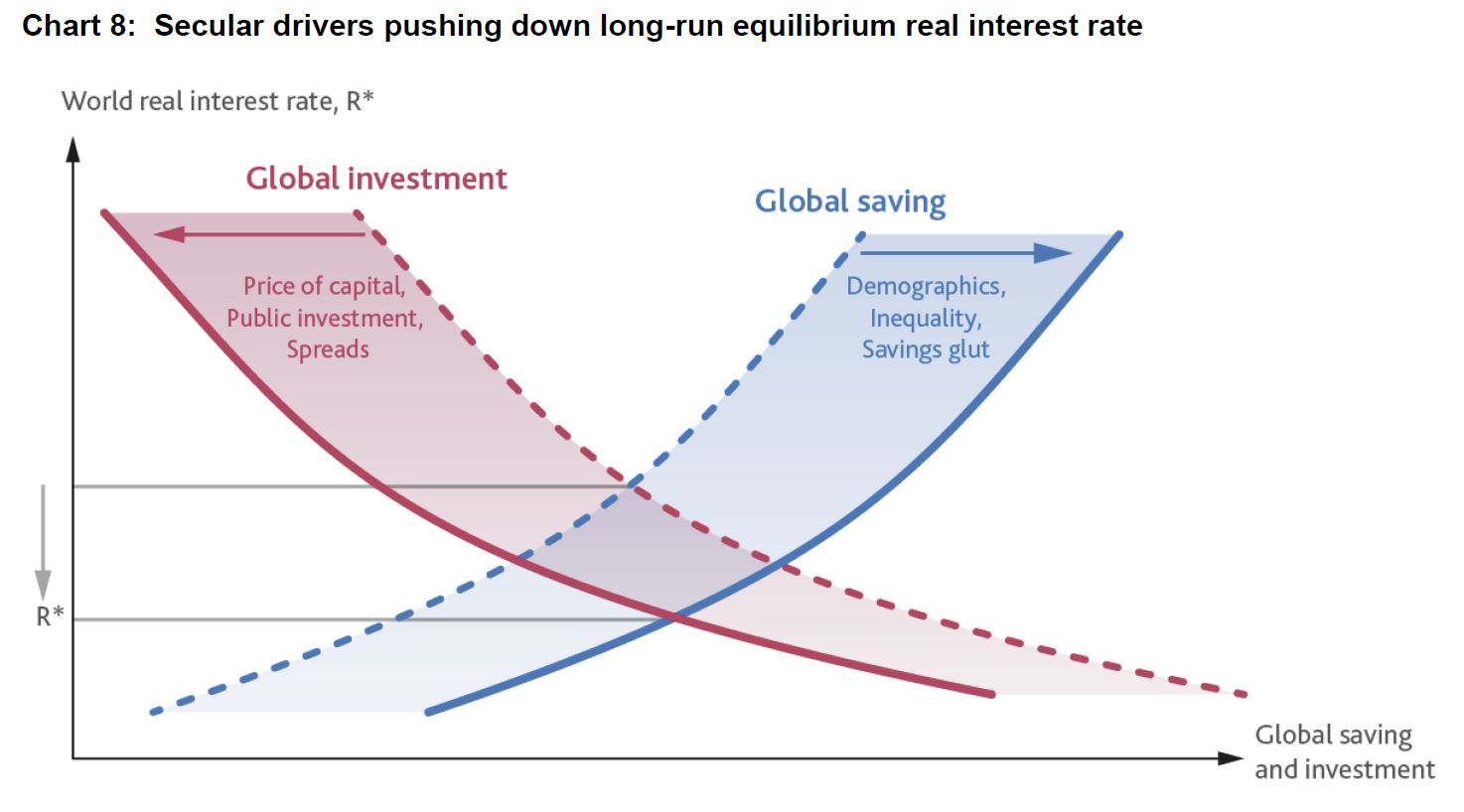

For the past thirty years, a number of profound forces in the world economy has pushed down on the level of world real interest rates by as much as 450 basis points. These forces include the lower relative price of capital (in part as a consequence of the de-materialising of investment), higher costs of financial intermediation (due to financial reforms), lower public investment and greater private deleveraging. Two other factors – demographics and the distribution of income – merit particular attention.

Bank research estimates that the increased retirement savings as a result of global population ageing and longer life expectancy have lowered the global real interest rate by around 140 basis points since 1990 and they could lead to a further 35 basis point fall by 2025. The crucial point is that these effects should persist after the demographic trends have stabilised because the stock, not the flow, of savings is what matters.

By changing the distribution of income, the global integration of labour markets may also lower global R*. The changes in relative wages in advanced economies have shifted income towards skilled workers, who have a relatively higher propensity to save. Rising incomes in emerging market economies may be reinforcing that effect as saving rates are structurally higher in emerging market economies, reflecting a variety of factors including different social safety regimes.

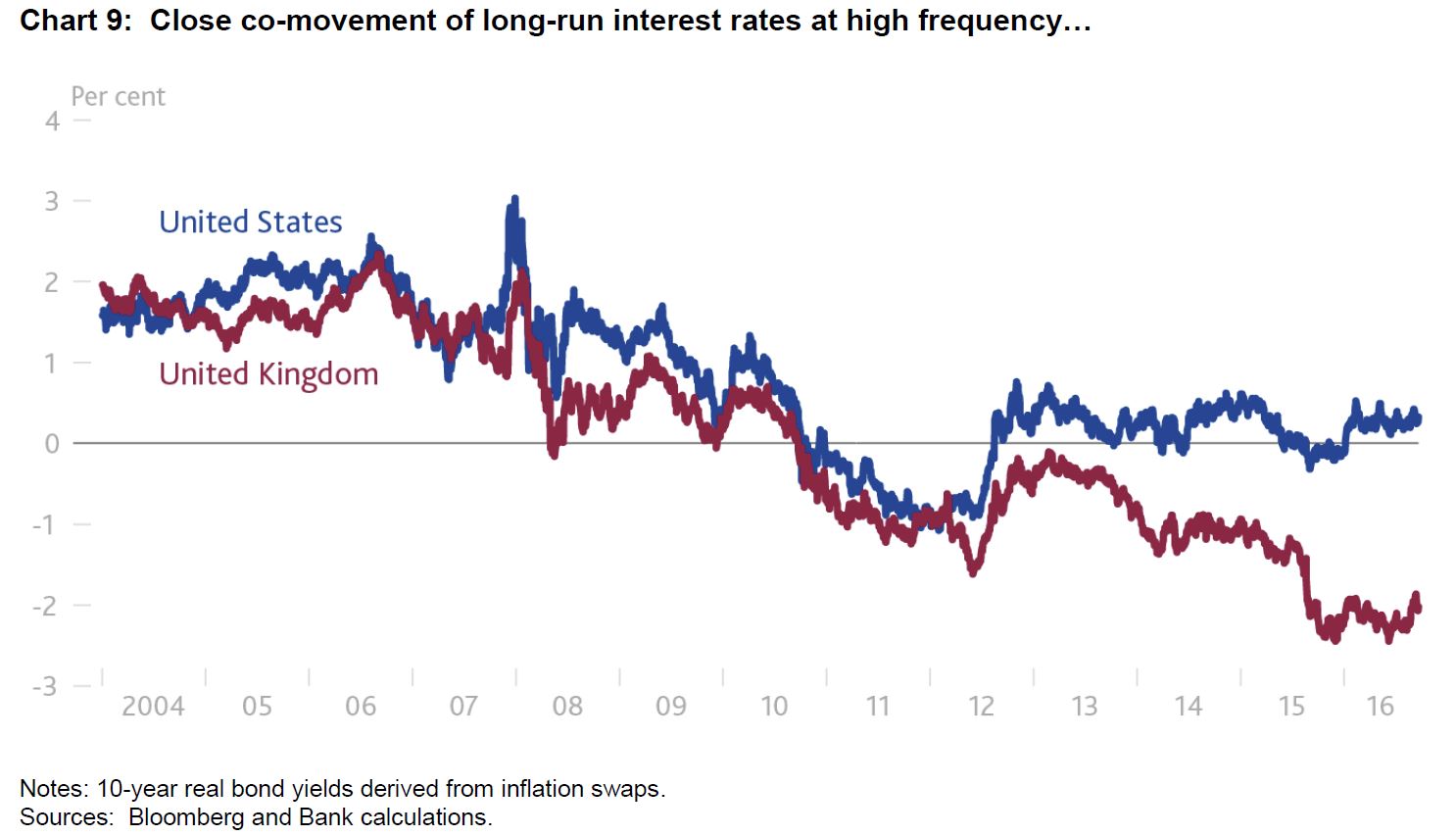

The high mobility of capital across borders means that returns to capital will move closely together across countries, with any marked divergences arbitraged.

As a consequence, global factors are the main drivers of domestic long-run real rates at both high and low frequencies. For example, Bank of England analysis suggests that about 75% of the movement in UK long-run equilibrium rates is driven by global factors. Estimates by economists at the Federal Reserve deliver similar results.

Global factors also influence domestic financial conditions and therefore the effective stance relative to the shorter-term equilibrium rate of monetary policy, r*.

The presence of borrowers and lenders operating in multiple currencies and in multiple countries creates multiple channels through which developments in financial conditions can be transmitted across countries. For example, changes in sentiment and risk aversion can lead to international co-movement in term premia, affecting collateral valuations and so borrowing conditions.

Work by researchers at the Bank of England, building on analysis by the IMF, shows that a single global factor accounts for more than 40% of the variation in domestic financial conditions across advanced economies. For the UK, which hosts the world’s leading global financial centre, the relationship is much tighter, at 70%.

Highlighting the openness of the UK economy and financial system, a third of the business-cycle variation in the UK policy rate can be attributed to shocks that originate abroad.

One important channel of global spillovers is of course monetary policy. In coming years, it is reasonable to expect global term premia to rise as net asset purchases could shift significantly from the situation during the past four years when all net issuance within the G4 was effectively absorbed.