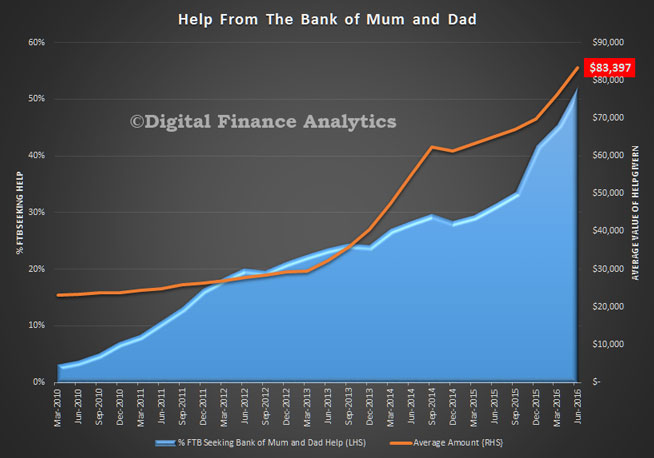

We highlighted recently that more first time buyers are getting help from “The Bank of Mum and Dad” to buy a property and the inter-generational issues this implies.

So we were interested to read this article from The Conversation, which uses a small sample of young people, but not focussing on those seeking to buy a property, as our research did. The average age of those we found seeking help were significantly older. We think younger people are more idealistic, whereas later the truth with dawn! However the call for greater financial literacy is correct.

So we were interested to read this article from The Conversation, which uses a small sample of young people, but not focussing on those seeking to buy a property, as our research did. The average age of those we found seeking help were significantly older. We think younger people are more idealistic, whereas later the truth with dawn! However the call for greater financial literacy is correct.

Despite the stereotypes of young people as a generation focused on spending with no consequences, young people actually see their money decisions (as well as their mistakes) as their responsibility, our research shows. They aren’t reliant on the “bank of mum and dad”.

We spoke to 123 Australians aged between 16-26 across a variety of socioeconomic groups. We asked them about their beliefs, perceptions when it comes to finance and how they made, spent and saved money.

Although parents “helping out” was mentioned – whether through direct money allowances or indirect support such as staying at home and paying marginal rent – it was clear young people saw their financial security as their responsibility.

However, many spoke of the desire to help out their families, particularly if their parents were struggling financially themselves. As a result, some young people chose to forego opportunities such as further study or training in favour of earning money in the present.

This has longer term consequences for their earning power. For example, they may be stuck in occupations characterised by precarious working conditions, low superannuation contributions and limited opportunities for promotion.

Many participants picked up on the gloomy sentiments around their generations’ prospects of home ownership, increasing precariousness of the labour market and the inevitability of working into their older age.

Young people faced a range of challenges, including lower wages in line with their age, unpaid overtime, delayed wages as casual part-time workers and exposure to exploitation and the cash economy. These all could undermine their attempts to save money and control their cash flow.

However, while focused on youthful consumption, many realise the need to balance this with achieving other medium and longer-term objectives – such as buying a car, or home ownership – and were optimistic of their ability to increase their earning power.

Our research also shows our squeamishness at talking about money has significant consequences for young people. The way we undertake financial literacy education often misses the mark.

Why we need to talk about money

In Australia we often think about money-talk as uncomfortable, boastful or even vulgar, even with intimate partners or close friends. Our study suggests this has significant consequences for future generations’ financial practices.

Although we may like to think our own positive money practices transmit to our children through a process of osmosis where they automatically model good financial practices, this was not the case for our participants.

Many found it difficult to articulate how their parents had been successful in saving, planning and spending beyond very general impressions.

However, others did describe how witnessing their parents deal with financial struggles influenced their own behaviours, particularly if they had made significant money mistakes. For these young people, early experiences of their family having no money for food, or memories of the electricity cut off due to late payment of bills influenced them in the long run. They had thought about strategies for budgeting and were clear about prioritising essentials such as rent.

But the cultural hangover of a hesitance to talk about money meant young people rarely reported discussing salaries, savings or longer term financial goals with their friends. Although they felt pressure to conform or keep up with activities or new products, many were perplexed that friends could afford something and they couldn’t, despite perceiving themselves to be in similar financial positions.

This may of course have dangerous consequences in terms of setting expectations about lifestyle or consumption choices that do not correlate with their financial practices.

Translating financial literacy into action

Our research suggests the current focus on financial literacy, which favours intervention and education at the individual level, only partially helps to support young people. Unlike previous generations, they face a complex terrain of financial decisions around superannuation, predatory lending practices (such as payday loans) and new, poorly regulated financial products on the market.

Among financial literacy initiatives, clear information is needed about the medium to long-term management of investments, the implications of debt and the importance of discussing their money decisions with others.

Most importantly, more needs to be done to ensure systems and practices around spending and financial commitments are accessible and transparent. This includes making it easy for people to “read the fine print” in agreements, and being clear about the longer-term consequences of financial decisions.

Young people have a clear idea what they want their futures to look like and they know it requires significant financial compromises and sacrifices in the short and medium term. The least we can do is provide enabling structures to support this.

, Associate Professor in Management, Monash University