AHURI is a national independent research network with an expert not-for-profit research management company, AHURI Limited, at its centre. AHURI undertakes evidence-based policy development on a range of priority policy topics that are of interest to our audience groups, including housing and labour markets, urban growth and renewal, planning and infrastructure development, housing supply and affordability, homelessness, economic productivity, and social cohesion and wellbeing.

The have just published a report – “Navigating a changing private rental

sector: opportunities and challenges for low-income renters“, utilising data from both HILDA, and other sources and using Clapham’s (2005) ‘housing pathways’ approach. As well as presenting data they also recommend a number of policy reforms.

This included HILDA data from 2015, which whilst dated now, highlights the issues in the low-income renter sector.

They say that the Private Rental Sector:

They say that the Private Rental Sector:

… has been expanding and transforming in a number of ways over the past decade as renters and investors/landlords adapt to rising house prices and rents, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne markets. At the low end of the sector, key developments have been the entry and expansion of the role of online platforms and community agency intermediaries in facilitating access to and tenancy management of private rental rooms and dwellings. The profile of renters is becoming more diverse as long-term renting continues to increase across all income groups, generating high competition for the limited dwellings that are affordable on a low income. The profile of investors/landlords and the lease lengths they choose to set for rooms and dwellings is also more varied.

They find that:

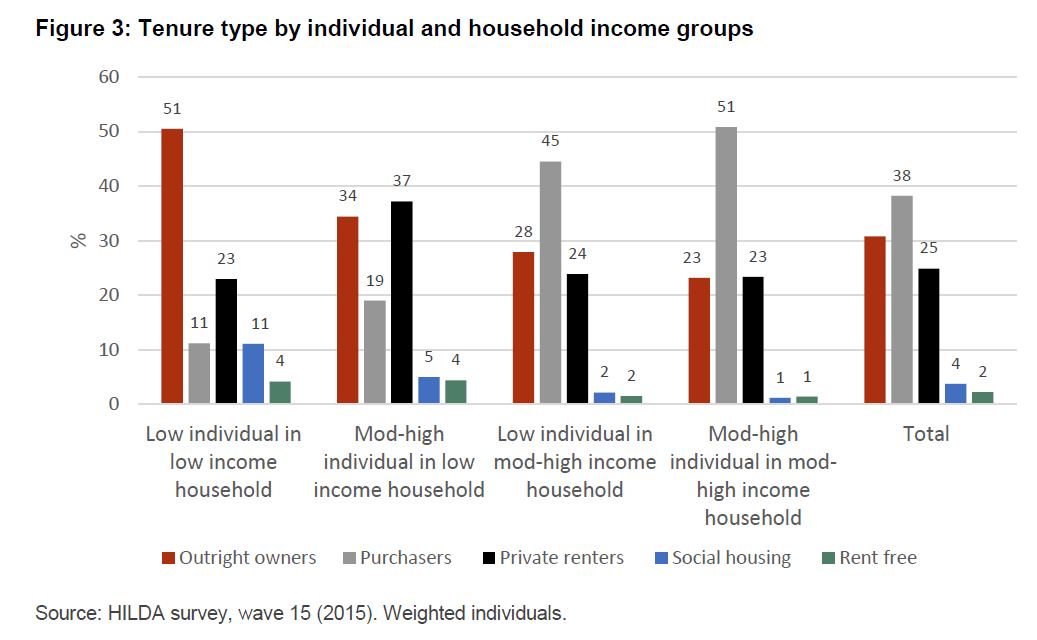

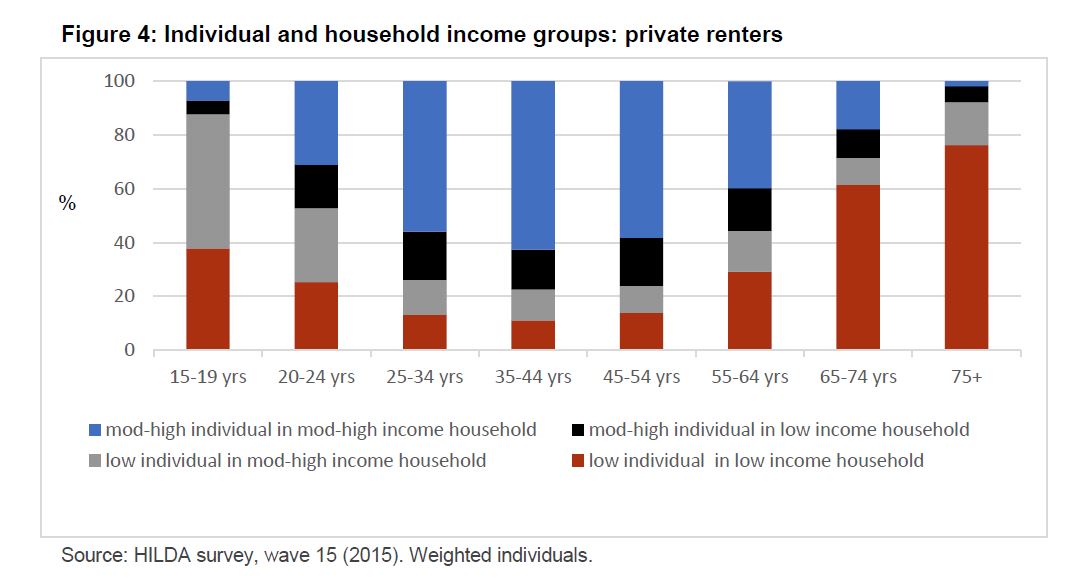

The accessibility and affordability of dwellings at the low end of the PRS undoubtedly remains the central issue for vulnerable groups of renters. In seeking to understand how low-income renters navigate changing PRS institutions, we first examine their individual and household income profile, drawing on existing HILDA and Journeys Home data. This background analysis reveals the importance of understanding the connection between individual and household income for low-income renters, beyond existing measures of affordability stress at the household level, which can conceal the difficulties faced by individuals as they navigate access to the PRS. Factors to be considered include the interim solutions individuals may seek when locked out of formal rental pathways (such as more informal or supported pathways into the PRS), and the consequences of persistently low individual and household incomes over time.

Applying an individual–household income typology within the HILDA data we find that:

- more than half (55%) of low-income (Q1–Q2) individuals in a low-income (Q1–Q2) household who are renting privately remain in this household group over a five-year period

- this group of private renters is most likely to make a transition into social housing and is less likely to move, but when they do move it is typically ‘forced’ (i.e. their property is no longer available to rent)

- low-income renters are least able, in terms of personal savings, to afford the upfront and relocation costs of a move.

In examining formal, informal and supported rental arrangements of individuals who have experience of or are at risk of homelessness, drawing on the Journeys Home longitudinal survey, we find the following.- Individuals and households in the lowest 20 per cent of the income distribution (Q1) are least likely to rent in the formal PRS, with over 70 per cent reporting a lack of affordable housing as an obstacle to finding more secure housing. The main type of living arrangements for those with Q1 individual (40%) and Q1 household (31%) incomes was renting from friends and family.

- Among Q1 individuals renting in the formal PRS, the main transition between consecutive waves of the HILDA data was to move into an informal arrangement where they rent privately from friends and family (24%).

- Transitions in individual income groups showed that 70 per cent of Q1 individuals and 74 per cent of Q2 individuals remained in the same income group over the data collection period (2011–14).

They state:

The formal institutions within the PRS designed to overcome barriers to accessing and managing tenancies for low-income renters have not kept up with the pace of change occurring within informal rental living arrangements. Any reforms to existing formal institutions intended to deliver better outcomes for private renters on a low-income must grapple with an increasingly complex and fragmented PRS. There is a clear need for centralised forms of assistance delivered via the statutory income system of support, but also a need for more devolved initiatives that can target informal and supported pathways through state and local government tenancy regulation and policy intervention. Within this framing, policy reform should take into account the following:

- Centralised reforms of rental housing assistance and regulation must seek to redress the growing imbalance in horizontal equity (treating those with similar incomes and wealth the same) and vertical equity (reducing the divide between those at the top and bottom of the income and wealth distribution). This includes reviewing the adequacy of wages, statutory incomes and rental assistance in view of rising costs of living.

- There is clear evidence that the informal pathway into the PRS is expanding through the reach of online platforms to exploit and disrupt formal paths to access and management. Regulation of informal rental practices, particularly in the context of online intermediaries and the growth of room rentals, must ensure that supply and access to urgent housing is not impeded, whilst also ensuring that tenants have adequate recourse to live in safe and secure rental housing.

- As the community sector expands its focus, there is growing capacity to establish more formal and enduring institutions at the low end of the PRS via a supported pathway delivered through an expanded community housing and welfare sector, in a similar manner to the social rental agencies developed in Belgium (see, for example, Parkinson and Parsell 2018). However, existing policy assumptions surrounding time-limited supported housing in the PRS, including financial subsidies through head-leasing initiatives, are highly problematic for those whose individual and household incomes remain low over time. A

AHURI Final Report No. 302 87

viable supported pathway into the PRS will require appropriate incentives for landlords to set their rents to be comparable with social housing rentals.- The emergence of different types of landlords (offering properties and rooms on a short- through to long-term basis), combined with the expanded reach of online platforms, provides opportunities for policy makers to assume a more direct role in better matching landlords with tenants. This includes targeting of landlord financial and taxation incentives to encourage supply of a mix of leasing options, dwelling types and locations at the low end of the market.

The findings and directions outlined in this report, together with those from an international and national institutional review of sector change and innovation, will inform the broader Inquiry report on The future of the private rental sector to provide a more detailed blueprint for institutional reform.