The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) announced a proposal to amend the existing mutual equity interest (MEI) framework to allow Australian mutually owned deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) to directly issue common equity Tier 1 (CET1) eligible capital instruments. The current framework only creates CET1-equivalent capital, so-called MEIs, through the conversion of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 capital instruments at the ADI’s point of non-viability. The amendment is credit positive because it would provide an additional option for mutuals to support balance sheet growth by raising high-quality capital. Australia’s mutuals have relied on retained earnings as their sole CET1 source because their mutual corporate status by definition has not allowed them to raise common equity.

APRA’s proposed amendment would allow mutuals to raise capital outside of extreme circumstances. The amendment also would provide a more efficient capital channel for mutuals to respond to growth opportunities. Mutuals thus far have relied on retained earnings accumulation as their primary source of CET1 capital. We view the proposal as an important step in levelling the playing field between mutuals and listed Australian ADIs, the latter of which have the ability to raise common equity.

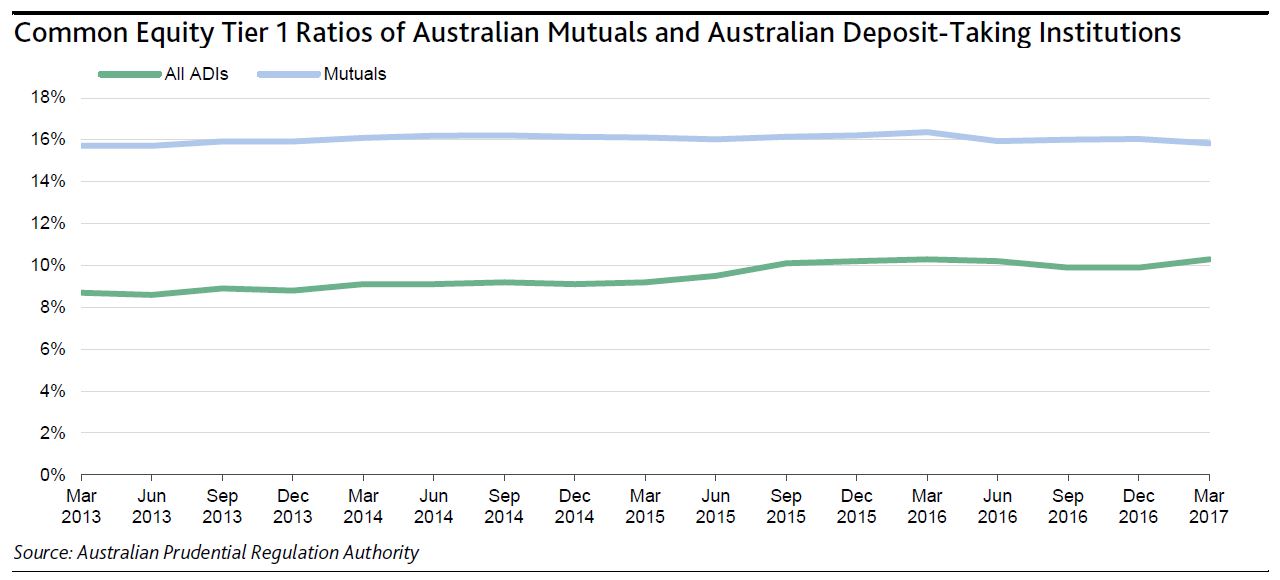

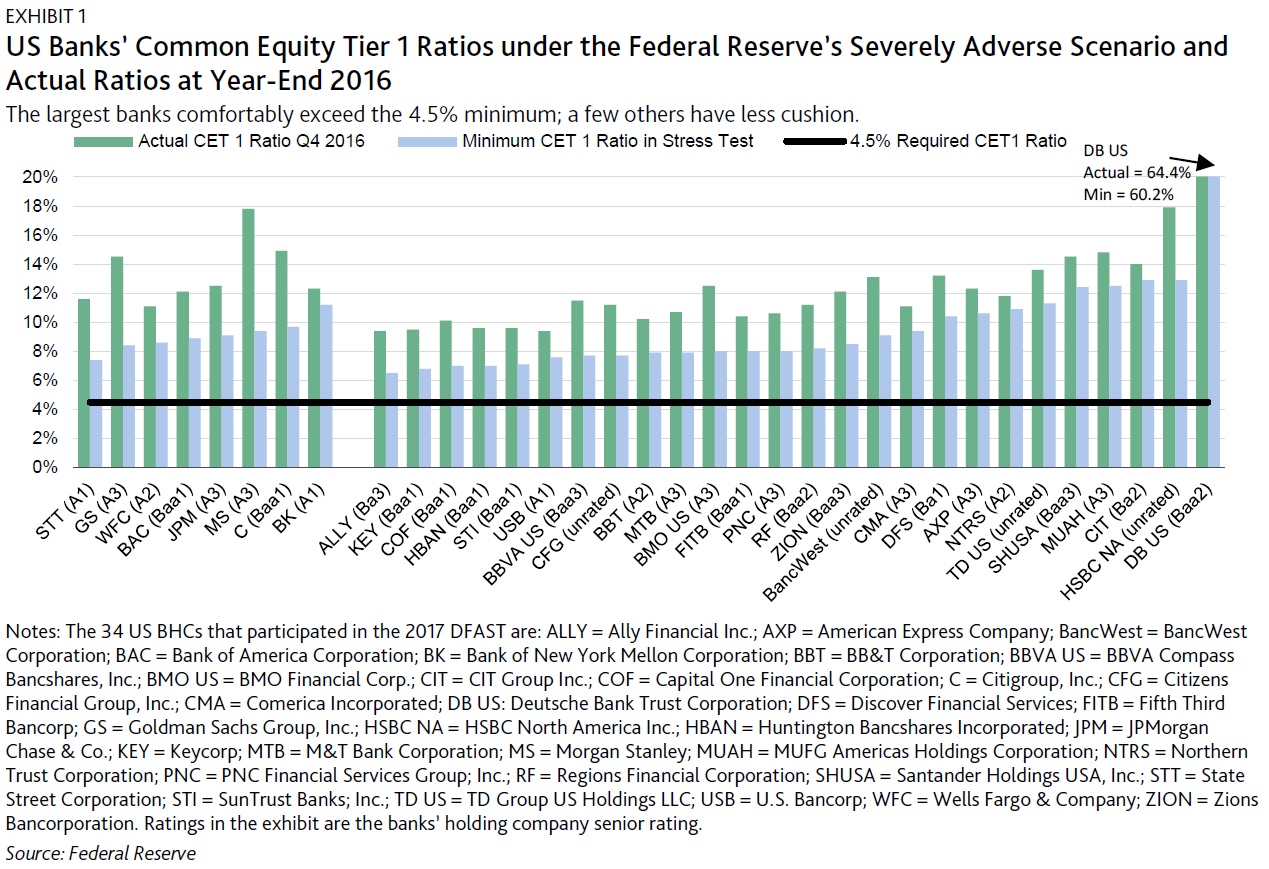

We do not expect the amendment, if enacted, to strongly increase common equity issuance to replace retained earnings as a dominant CET1 capital source because of mutuals’ already-strong capitalization and the limits that APRA will set on such instruments. Australia’s mutuals have no urgent need to boost their capital ratios. The exhibit below shows that mutuals have consistently reported higher average CET1 ratios than other ADIs. As of the end of March 2017, their aggregate CET1 ratio was 15.8%, versus 10.3% for all ADIs.

Under the current MEI framework, which has been in place since 2014, Moody’s-rated mutuals have 2% of their total capital as AT1 and Tier 2 instruments. (Moody’s-rated mutuals make up approximately 50% of the mutual sector’s total assets.)

The regulator also limits mutuals’ ability to rely on MEI-created CET1 (either through conversion of AT1 and Tier 2 instruments or direct issuance). Specifically, APRA has proposed a 15% cap on the inclusion of MEIs in CET1 capital, and distribution of profits to MEI investors at 50% of ADIs’ net profit after tax on an annual basis.

We expect that MEIs will continue to account for only a minor share of mutuals’ capital, which alleviates the risk that the APRA proposal will incentivize mutuals to maximize their profitability to meet MEI investors’ dividend payment expectations. This scenario would conflict with mutual ADIs’ traditional business model that de-emphasizes profit maximization, and instead focuses on providing value to members via cheaper loans and higher-yielding deposits.