The latest Statement of Monetary Policy, released today, continues to tell the now well rehearsed story. Resources down, China under pressure, local growth slowish, and transitioning from mining, sort of working, whilst home lending continues to grow at above 7% annually. But they kick around two interesting issues. First, why is the unemployment rate so good when growth is sluggish, and second why is the household savings ratio lower now?

Looking at employment first:

…strong employment growth has also been supported by a protracted period of low wage growth which, along with the exchange rate depreciation, may have encouraged firms to employ more people than otherwise. At the same time, growth in the supply of labour has increased through a rise in the participation rate, notwithstanding lower population growth. The unemployment rate declined to around 5¾ per cent in late 2015, having been within a range between 6 and 6¼ per cent since mid 2014. Nevertheless, there is evidence of spare capacity in the labour market, as the unemployment rate is still above recent lows, the participation rate remains below its previous peak and wage growth continues to be low.

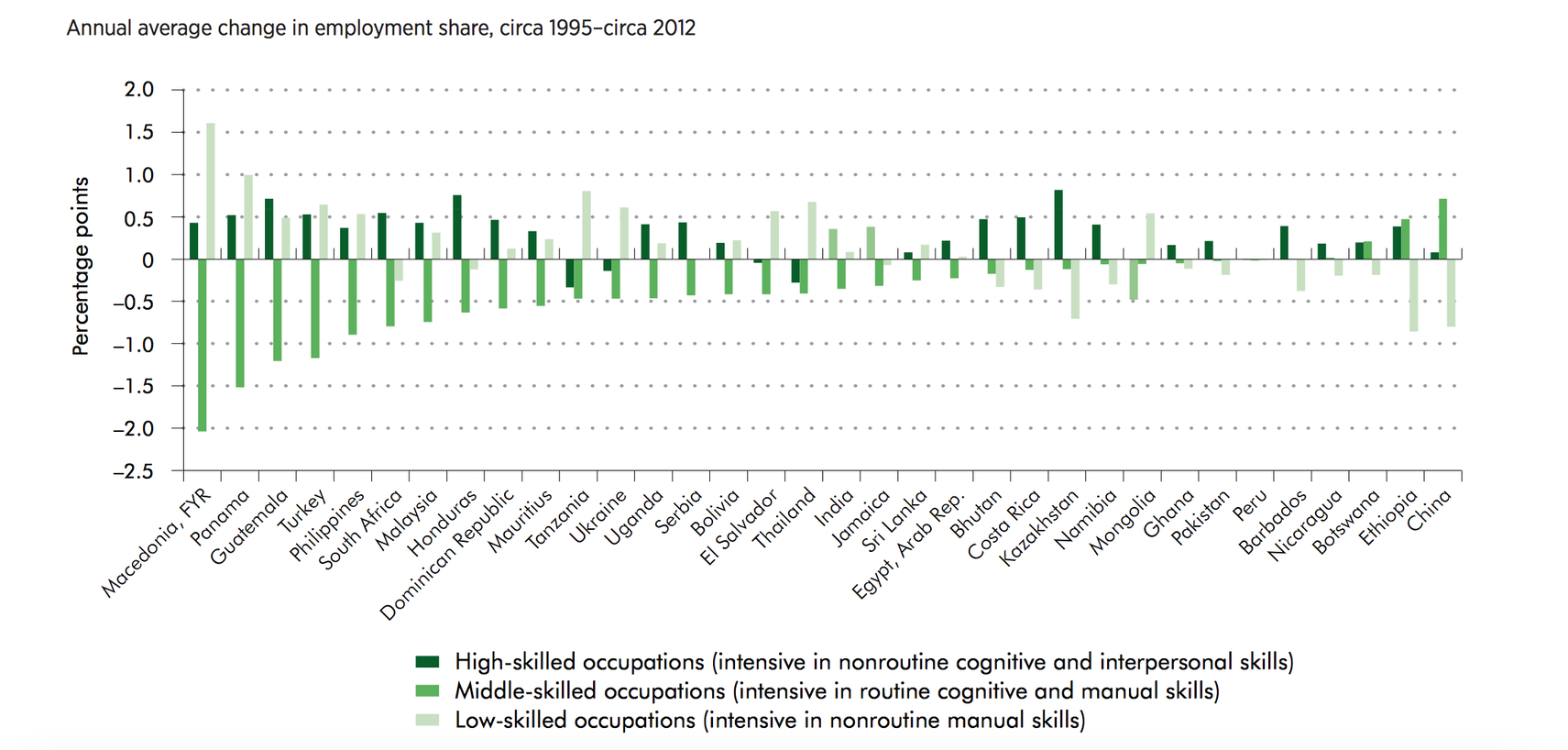

Also, the low growth of wages is likely to have encouraged businesses to employ more people than otherwise. Measures of job vacancies and advertisements point to further growth in employment over the coming months. In response to this flow of data, the forecast for the unemployment rate has been revised lower. The fact that the improvement in labour market conditions has occurred against the backdrop of below-average GDP growth raises some uncertainty about the economic outlook. It is possible that the strength in the labour market data contains information about the economy not apparent in the national accounts data, or that the strong growth in employment of late will be followed by a period of weaker employment growth. Alternatively, the strength in labour market conditions relative to output growth may reflect a rebalancing of the pattern of growth towards labour intensive sectors and away from capital intensive sectors.

DFA is of the view that the growth in lower-paid non-wealth producing jobs at the expense of productive jobs is the key – more are now working in the healthcare and services sector (in response to growing demand thanks to demographic shifts), but it just moves the dollar around the system, and does not create new dollars. There is difference between being busy, and being productively (economically speaking) busy.

Turning to the savings ratio:

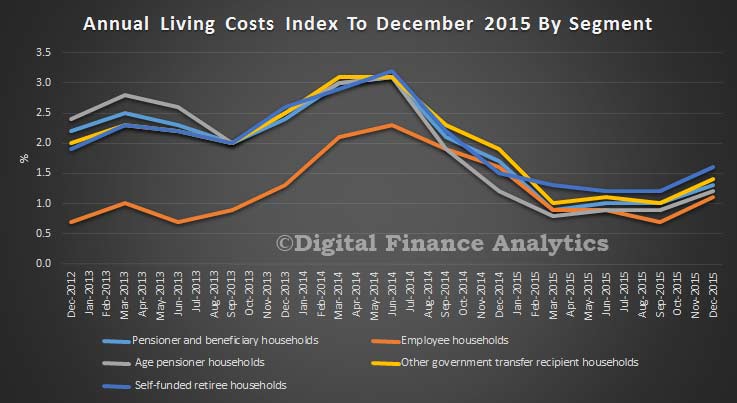

… after falling for more than two decades, the aggregate household saving ratio in Australia increased sharply in the latter half of the 2000s. While it has since remained close to 10 per cent – which implies that, collectively, households have been saving about 10 per cent of their incomes – the saving ratio has declined modestly over the past three years or so.

Understanding developments in the saving ratio is important because changes in household saving behaviour can have implications for the outlook for aggregate consumption. Trends in the household saving ratio in Australia over recent years are likely to reflect a range of factors, including the effect of the boom in commodity prices and mining investment on household incomes, behavioural changes stemming from the global financial crisis, and the current low level of interest rates. Longer-term factors such as financial deregulation and population ageing have also played a role. Households’ expectations about future income growth and asset valuations, and the uncertainty around those expectations, are also relevant to their saving decisions. Many households accumulate precautionary savings to insure against an unanticipated loss of future income or unexpected expenditure (such as on a medical procedure). At the macroeconomic level, precautionary saving is likely to be particularly important if households are very risk averse or constrained in their ability to borrow to fund consumption when their incomes are temporarily low. For example, the financial crisis is likely to have made households more uncertain about their future employment or income growth and/or led them to reassess their tolerance for risk, which would have encouraged them to increase their rate of saving. Surveys at that time showed an increase in the share of households nominating bank deposits or paying down debt as the ‘wisest place for saving’, although this may have also reflected lower expected rates of return on other financial assets following the financial crisis.

The level of interest rates can also influence the saving ratio. On the one hand, the current low level of interest rates reduces both the return to saving and the cost of borrowing, which encourages households to bring forward consumption; this might explain some of the recent decline in the aggregate household saving ratio. Low interest rates also support the value of household assets, which increases the amount of collateral households can borrow against, and potentially reduces the incentives for households to save. On the other hand, the household sector in aggregate holds more debt than interest-earning assets, so cyclically low interest rates provide a temporary boost to disposable income through a reduction in net interest payments, some of which may be saved. Households also need to save more to achieve a given target level of savings when interest rates are low.

Structural changes to the Australian financial system have been important longer-term drivers of changes in household saving behaviour. Financial deregulation in the 1980s and a structural shift to low inflation and low interest rates in the 1990s allowed households that were previously credit constrained to accumulate higher levels of debt for a given level of income. This rise in indebtedness was accompanied by strong growth in housing prices and a reduction in the household saving ratio to unusually low levels. In this way households were able to support consumption via the withdrawal of housing equity. Innovation in financial products – such as credit cards and home-equity loans – also gave households much better access to finance. The adjustment to these structural changes in the financial system appears to have largely run its course by the mid 2000s.

The ageing of the population is another longer-term influence on the saving ratio. If shares of younger and older households in the population were constant over time, the different saving behaviours of these households would not affect the aggregate saving ratio. However, Australia’s baby-boomer generation is a larger share of the population now and has been entering the retirement phase since around 2010. Because households save less in their later years, this is expected to have a gradual but long-lasting downward influence on the aggregate household saving ratio. However, a potentially offsetting influence is rising longevity, which may lead households to save more during their working years to finance a longer period of retirement.

The amount that each of these drivers have contributed to recent trends in the aggregate household saving ratio is unclear. It is also uncertain how they will evolve over the next few years, although the Bank’s central forecast embodies a further modest decline in the saving ratio, that reflects, in part, the unwinding of the impact on saving from the earlier boom in commodity prices and mining investment.

Using data from the DFA household surveys, we note three factors in play. First, household confidence levels still below long term trends, so we would expect households to continue to save, if they can, against perceived future risks. Second, older households hold the bulk of the savings, and they are indeed growing as a proportion of the total, so again we would expect to see a rise, not a fall in the ratio. But, the third factor, is in our view, the most significant. That is that many are relying on income from savings, and as deposit interest rates have fallen (and alternative investment options become more risky), some have switched savings into investment property and others are having to eat into capital to survive. The RBA’s policy settings of low interest rates, and high house prices are being reflected back in lower savings ratios.