The Bank for International Settlements just released a working paper – “How Does Bank Capital Affect the Supply of Mortgages? Evidence from a Randomized Experiment.” Given the intense focus on banks lifting capital ratios, this is an important question. They conclude that higher bank capital is associated with a higher likelihood of application acceptance and lower offered interest rates, whilst banks with lower capital reject applications by riskier borrowers and offer lower rates to safer ones. In other words, changing capital ratios directly and indirectly impact lending policy, but not necessarily in a linear or expect way.

The recent financial crisis refocused the attention on how the health of banks affects financial stability and macroeconomic growth. In particular, the academic and policy debates currently center on the effects of bank capital on lending and risk-taking. Indeed, both macroprudential and the microprudential regulatory reforms propose to raise bank capital ratios and strengthen bank capital buffers, with the aim of preventing “excessive” lending growth and increasing the system’s resilience to adverse shocks.

Yet, there is only a limited degree of consensus on the effect of higher bank capital on lending. On the one hand, higher bank capital increases both the risk-bearing capacity of banks and incentives to screen and monitor borrowers, in this way boosting lending. On the other hand, as debt creates the right incentives for bankers to collect payments from borrowers, lower debt and higher capital may reduce banks’ lending and liquidity creation.

In this paper we study the effect of bank capital on banks’ propensity to grant mortgages and on their pricing. We also explore how bank capital affects the selection of borrowers and the characteristics of offered mortgages, deriving implications for risk-taking. Finally, to detect possible non-linearities, we provide nonparametric estimates.

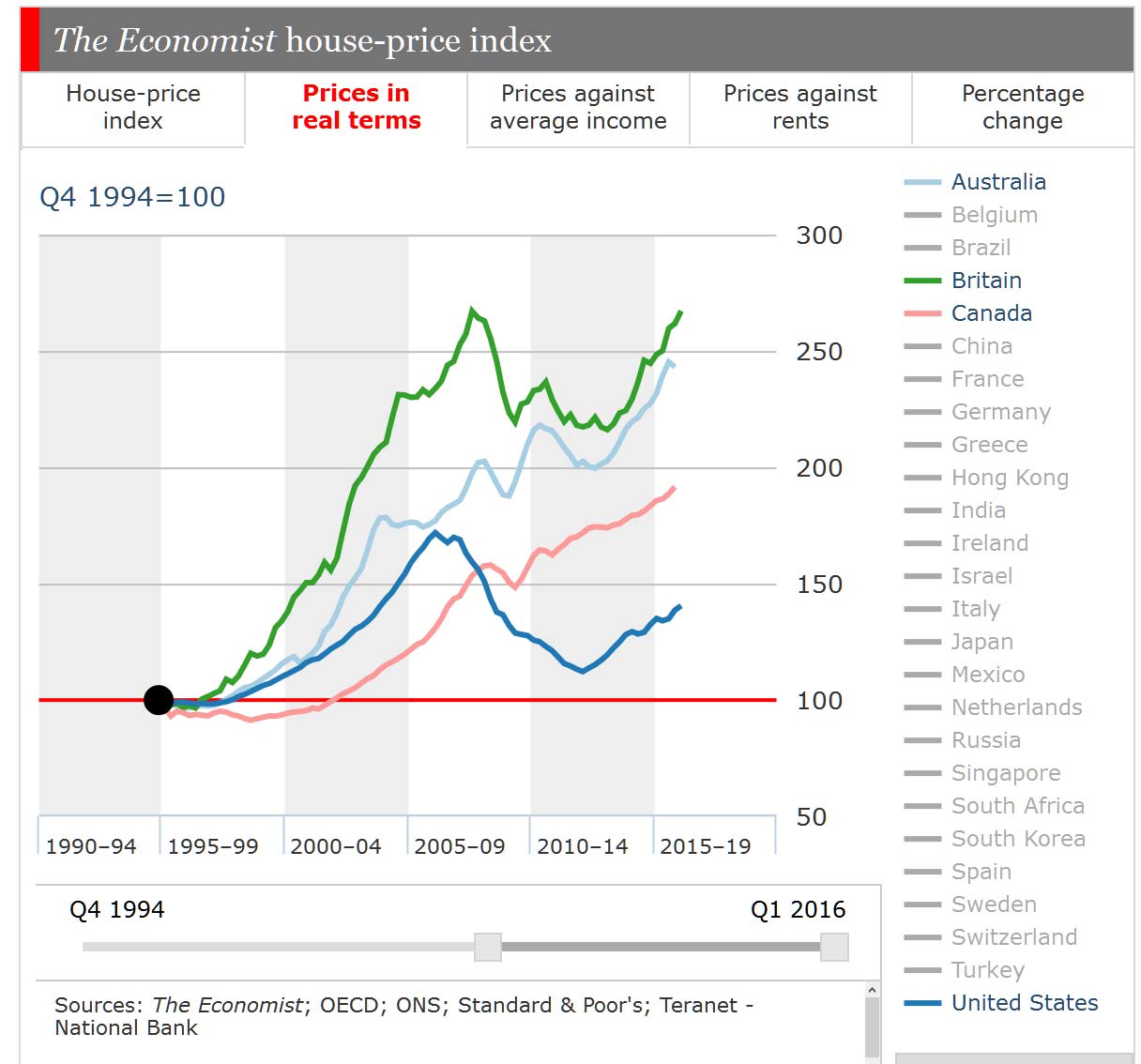

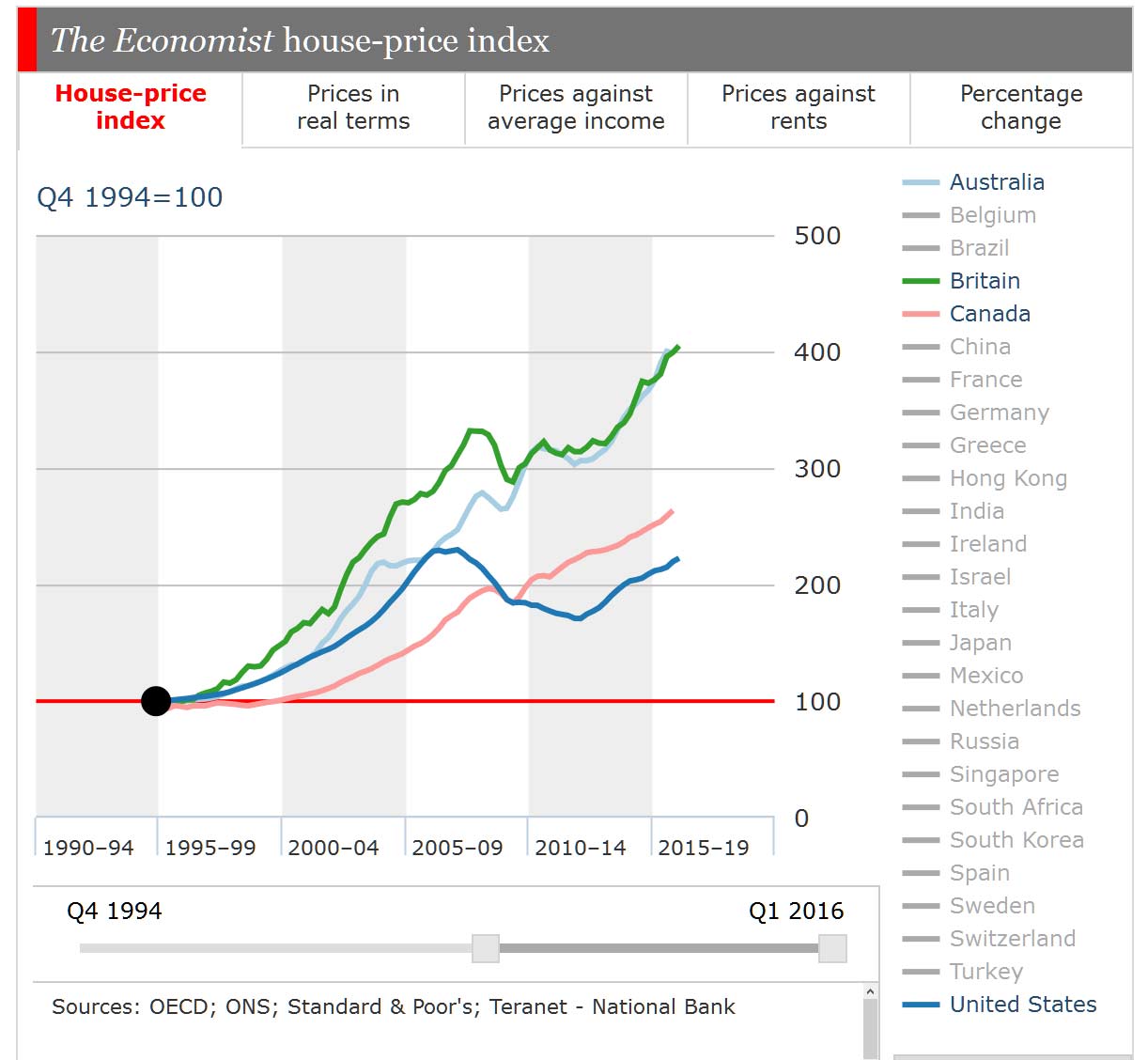

We focus on mortgages, whose relevance for both macroeconomics and financial stability has been unquestionable following the 2007-2008 financial crisis. In the first half of the 2000s, a strong increase in mortgage originations fueled a housing boom in several countries (US, UK, Spain, Ireland). That boom in turn led to a high accumulation of risks, which subsequently materialized causing the failure of several banks and a large drop in house prices. Understanding how bank capital affects mortgage originations and the way banks select the risk profiles of borrowers is thus critical to evaluate developments in the mortgage market and the potential accumulation of both idiosyncratic and systemic risks.

We use a new and unique dataset of mortgage applications and contract offers obtained through a randomized experiment. In particular, we post randomized mortgage applications to the major online mortgage broker in Italy (MutuiOn-line) in two dates (October 16, 2014, and January 12, 2015). Upon submitting any application, the online broker requires prospective borrowers to list both their demographic characteristics (income, age, job type) and the main features of the contract requested (amount, duration, rate type). By varying those characteristics, we create profiles of several “typical” borrowers who are submitting distinct applications for first home mortgages. Crucially, through the online broker all participating banks (which include the 10 largest banks in the country accounting for over 70% of the market for mortgage originations) receive the same mortgage applications, defined by the same borrower and loan characteristics. Hence, our estimates are not biased by the endogenous selection of borrowers into contracts or banks and, furthermore, there are no missing data due to discouraged potential borrowers not submitting applications. We then merge those data with the banks’ characteristics from the supervisory reports and, in our empirical analysis, we include several bank-level controls to reduce concerns about omitted variable bias; we exploit the time dimension of our data and we include bank fixed effects to control for unobserved determinants of bank capital in the cross-section; finally, in some specifications, we include bank*time fixed effects, to fully account for all bank specific, time-varying characteristics.

On the one hand, we find that banks with higher capital ratios are more likely to accept mortgage applications and to offer lower APRs. On the other hand, banks with lower capital ratios accept less risky borrowers. However, we cannot rule out that less well-capitalized banks take more risk on other assets (business loans, securities).

We also provide a quantitative estimate of the effect of bank capital ratio on the supply of mortgages, using a nonparametric approach. We find that the capital ratio has a non-linear effect on the probability of acceptance, stronger at low values of the ratio, almost zero for higher values. This non-linearity is more pronounced when the borrower or the contract are riskier.

Note: BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The papers are on subjects of topical interest and are technical in character. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS.