Inflation dynamics and its interaction with unemployment seem to be behaving differently since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Are external factors such as low interest rates and credit availability and other external variables influencing the current apparent dislocation of the assumed relationship between inflation and unemployment? Or is the underlying relationship, as described in the so called Phillips curve at fault? Perhaps we cannot assume, all else being equal, that in the current economic climate, lower levels of unemployment will necessarily translate to higher inflation.

The Phillips curve is a single-equation empirical model, named after A. W. Phillips, describing a historical inverse relationship between rates of unemployment and corresponding rates of inflation that result within an economy. Stated simply, decreased unemployment, (i.e., increased levels of employment) in an economy will correlate with higher rates of inflation. (Wikipedia).

Is the Phillips curve broken? This question is a central topic in macroeconomics as modified forms of the Phillips Curve that take inflationary expectations into account remain influential. Modern Phillips curve models include both a short-run Phillips Curve and a long-run Phillips Curve. This is because in the short run, there is generally an inverse relationship between inflation and the unemployment rate; as illustrated in the downward sloping short-run Phillips curve. In the long run, that relationship breaks down and the economy eventually returns to the natural rate of unemployment regardless of the inflation rate.

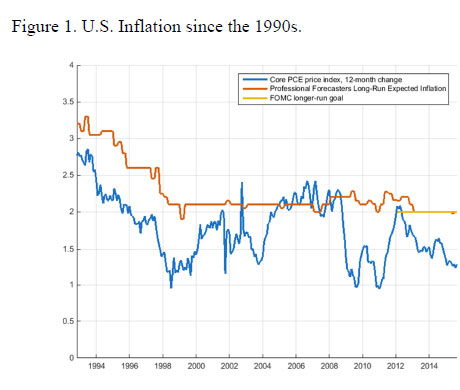

The key question is – how does unemployment affect inflation? Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009, while inflation has declined, it has fallen less than was anticipated (an outcome referred to as the “missing disinflation”). More recently the currently low unemployment rates should have pushed the inflation rate closer to the Federal Open Market Committee’s longer-run inflation goal, but inflation has been running below the 2 percent target for an extended period.

So an IMF working paper “Did the global financial crisis break the US Phillips Curve?” is worth looking at.

So an IMF working paper “Did the global financial crisis break the US Phillips Curve?” is worth looking at.

Clearly, if confirmed, a changing or non-linear, relation between inflation and unemployment would have significant implications for monetary policy. While a linear Phillips curve warrants a symmetric monetary policy response with respect to business cycle conditions, a nonlinear Phillips curve, where inflation increases rapidly when unemployment rate declines below the natural rate may imply preemptive measures are needed to counter inflation when the economy is closer to potential. If, on the other hand, the Phillips curve is very flat monetary policy should react more strongly to unemployment movements, relative to inflation.

In this paper, we shed light on the forces and, possibly changing, dynamics between inflation and activity since the GFC. In other words, did the GFC break the U.S. Phillips curve? Moreover, we investigate three hypotheses which have recently been put forward as factors which could explain why inflation is currently low:

(a) Financial frictions, and shocks could imply slow recoveries and persistently low inflation.

(b) Globalization has increased the role of international factors and decreased the role of domestic factors in the inflation process in industrial economies. These hypotheses originated from the concerns of some monetary policymakers of an increasing disconnect between monetary policy on one side and domestic inflation and long-term interest rates on the other.

(c) the last hypothesis pertains to the inability of stabilization policy – due to the effective lower bound on policy rates – to lower real interest rates enough to bring the economy back to long-run sustainable levels and to achieve long-run inflation goals. Policymakers have emphasized how persistently low inflation poses substantial risks if monetary policy is constrained by the zero bound, and could derail the economic recovery .

Using extensive modelling they examine a series of “(possibly) nonlinear vector stochastic dynamic process(es)”. They took account of the Federal Reserve lowered the federal funds rate to the zero lower bound (ZLB) where it remained until December 2015. “Once the ZLB, or a negative Shadow Funds rate, is obtained, the perception, if applicable, that the funds rate reacts differently e.g. can fall no further, would be captured by switching in coefficients plus switching in shock variances such that adverse shocks to the Shadow funds rate are obtained. Second, there could be a change in the relationship between the federal funds rate and the term spread either directly because of the negative Shadow rates, or because of nonstandard monetary policy measures that stand in for conventional monetary policy. This is the main reason why the term spread is included as a variable in the model”. They conclude:

We use large BVAR’s, DFM’s and MS-VAR models to investigate the possibility of non-linearity in the recent post-crisis dynamic of inflation and unemployment rate in U.S. data. In other words, did the GFC break the U.S. Phillips curve? We also study what conditioning information set is informative for inflation and unemployment. We find that changes in shocks is a more salient feature of the data than changes in coefficients and a model with time-varying coefficients in the policy rule fits better than all other models that allow a change in coefficients. The model with coefficient switching in the simple instrument rule with variance switching in all equations attain the highest marginal data density.

Moreover, conditional forecasts which condition on external variables and financial risk variables seems to come closest to describing the dynamics of inflation while credit variables are the most important conditioning variables of the post-GFC unemployment rate.

We show that financial and external variables have the highest forecasting power for inflation and unemployment, post-GFC.

In other words, the Phillips curve is not broken, but is swamped by external factors, which makes it a less useful and authoritative tool. We cannot assume, all else being equal, that in the current economic climate, lower levels of unemployment will necessarily translate to higher inflation. We think the missing and critical factor is low, or falling real wages.

Note: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.