According to Moody’s, Canada’s national banking and insurance regulator, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI), published for comment draft guidelines on changes to capital requirements for mortgage creditor insurers.

The draft advisory provides a new standard approach for residential mortgage insurance that is more risk sensitive and incorporates new key risk and loss drivers including creditworthiness, remaining amortization, and outstanding loan balances.

These new capital requirements, if implemented as drafted, would increase overall capital for Canada’s mortgage insurance industry and Canadian Crown corporation, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, a credit positive.

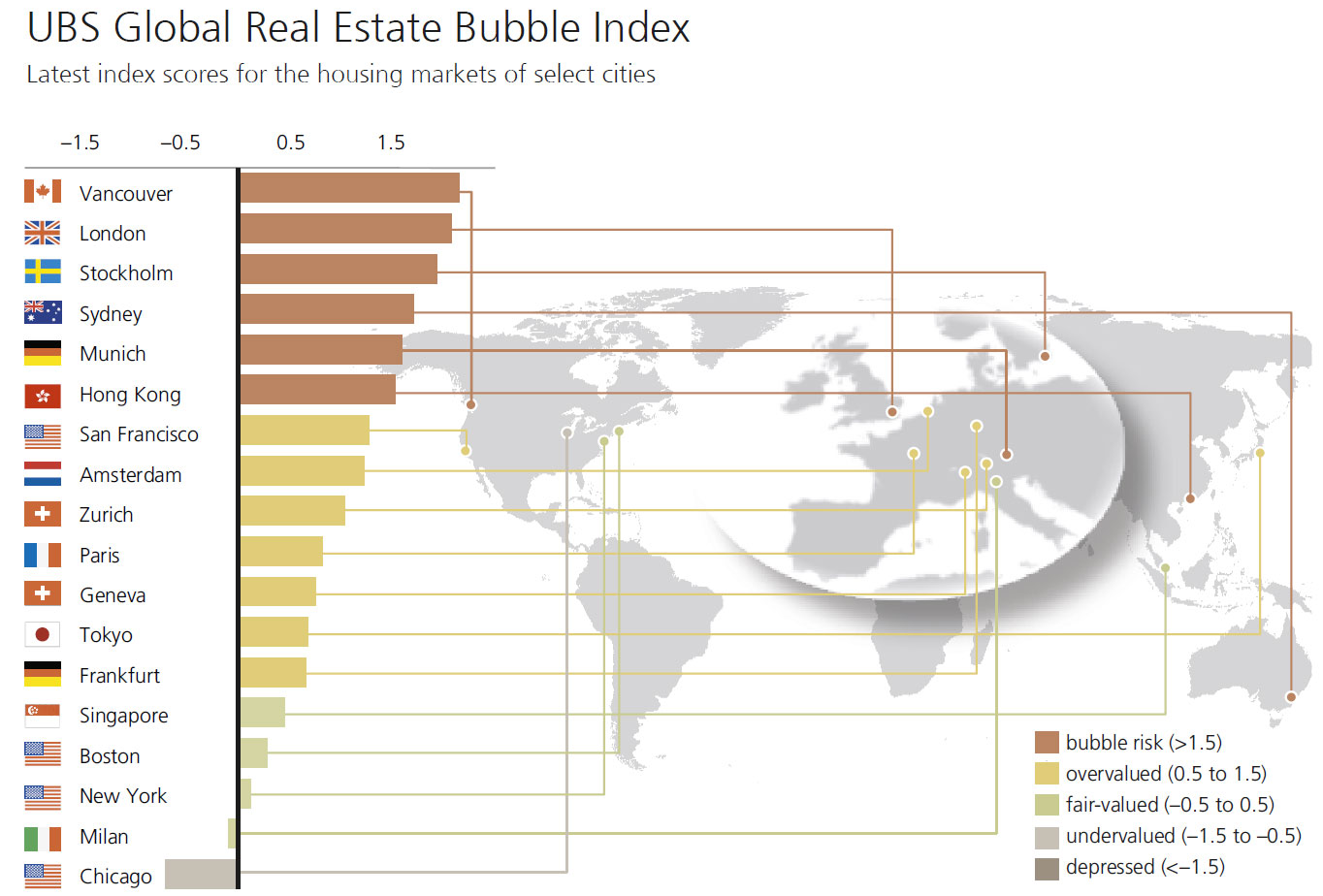

The draft guidelines require a supplemental capital requirement for mortgages insured in Canada’s 11 largest metropolitan areas when those cities show indications of high house prices relative to income levels, similar to bank capital requirements introduced earlier this year. This supplemental charge will create a capital cushion for mortgage insurers’ exposures in cities whose housing markets have had rapid price appreciation, such as Vancouver, British Columbia, and Toronto, Ontario. We believe required capital for mortgages in

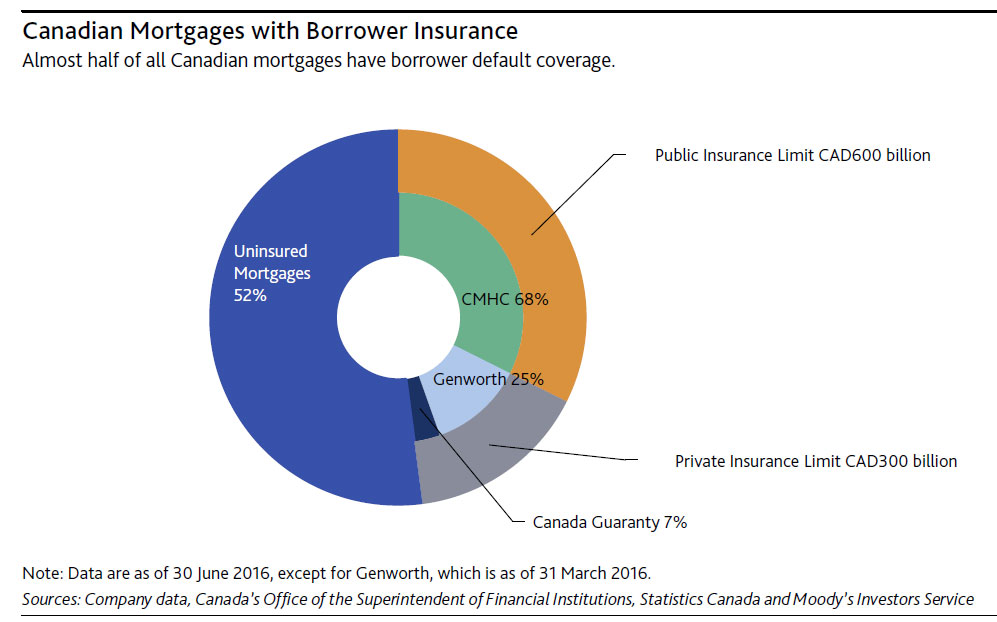

these cities will increase.Of the CAD1.6 trillion in outstanding Canadian mortgage debt, including home equity lines of the credit, almost half are covered by creditor insurance (see exhibit). This insurance is primarily sold either directly to the borrower, who is legally required under the Bank Act to obtain it if the mortgage’s loan-to-value ratio exceeds 80%, or lenders purchase the insurance on a portfolio basis as a liquidity and capital management tool.

The Canadian government limits its mortgage insurance guarantee to CAD900 billion, which is shared among only three entities. CMHC, which as a crown corporation with government agency status, effectively makes any policies it writes a direct contract with Canadian government. Under legislation, CMHC’s insurance-in-force is limited to CAD600 billion. The Canadian government also provides a 90% guarantee on the insurance in force of two private-sector insurers, Genworth and Canadian Guaranty Insurance Company of Canada, in the event that one of them fails. This CAD300 billion guarantee is shared between the two insurers.

These and other recent actions by Canadian policymakers will assist in slowing rapid house price appreciation and corresponding mortgage growth, reducing the prospect of a sharp housing price correction that would increase credit losses at Canadian banks. Increasingly, elevated housing prices have driven up Canadian household indebtedness, a key threat to the stability of the Canadian banking system. Since 2008, Canadian policymakers have implemented a series of changes to the rules for government-backed insurance, including limitations on amortization, premium increases and elimination of specialized product offerings.

We do not believe this has any credit implications for Canadian banks that hold insured mortgages because their exposures to mortgage insurers are already backstopped by the Canadian government.