Where do most digitally active households reside? This is becoming an increasingly important question, as mobile penetration and use climbs. It fundamentally changes the optimal marketing approach and channel strategy.

Using data from our household surveys we track the proportion of households with a preference for using digital devices – especially smartphones – for their banking interactions and other online activities. The latest data, which will flow in due course to our next edition of the Quiet Revolution – our channel analysis report – shows that there are large numbers of digitally savvy consumers and small businesses who want more digital, and less branch. They want a “mobile first” offering.

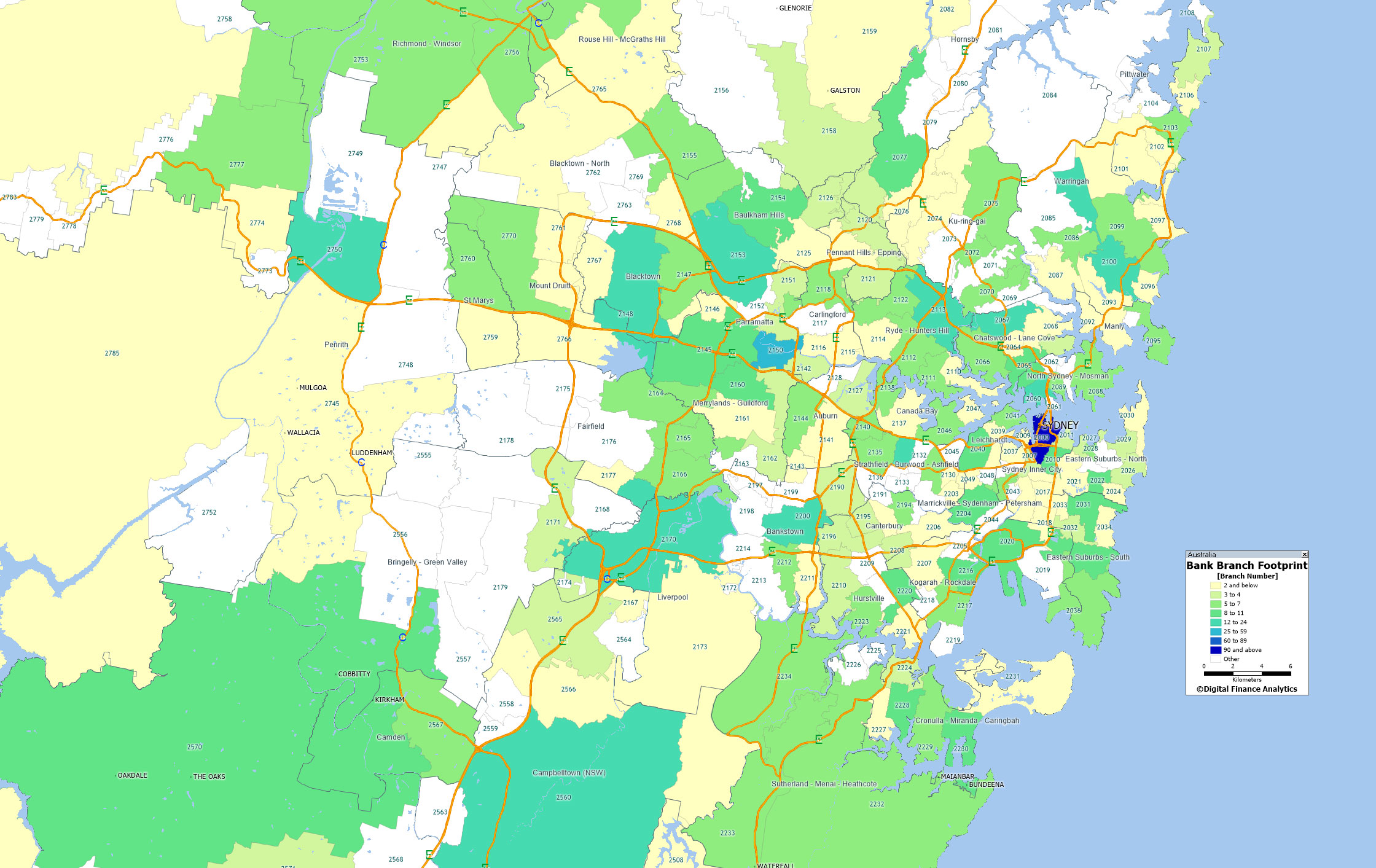

To illustrate this we have mapped the number of households by digital segments – identifying those seeking a mobile first solution – to postcodes. Then we also map the current branch representation, based on the latest APRA points of Presence report. There is a striking mismatch between the two.

Lets take the Sydney area as an example. Below is the branch representation, with the largest number of branches in the Sydney CBD, and a smattering across the region.

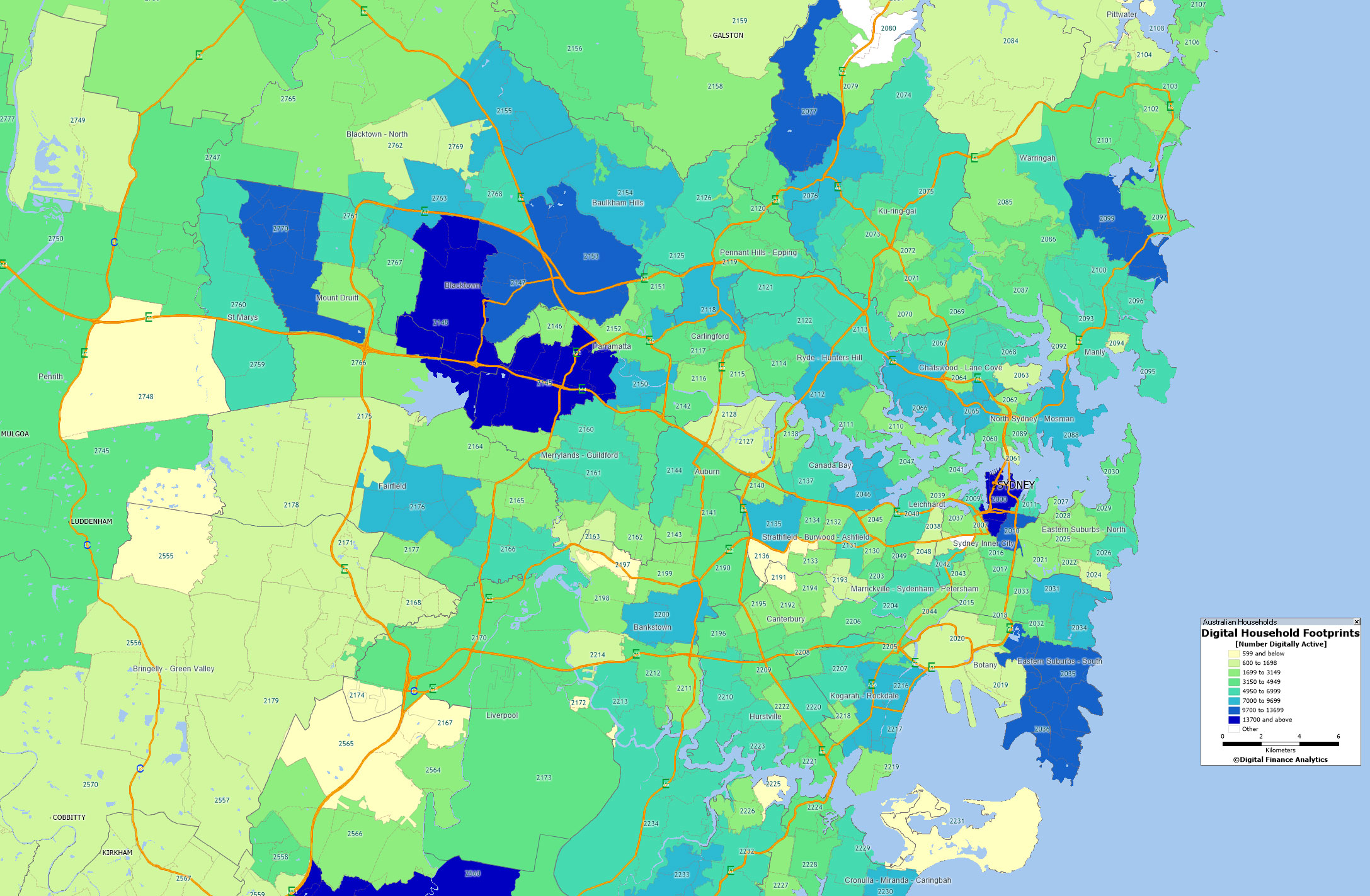

Now looking at the representation of mobile first households, we see a very large number in Sydney CBD, as well as hot spots across the Sydney basin.

Now looking at the representation of mobile first households, we see a very large number in Sydney CBD, as well as hot spots across the Sydney basin.

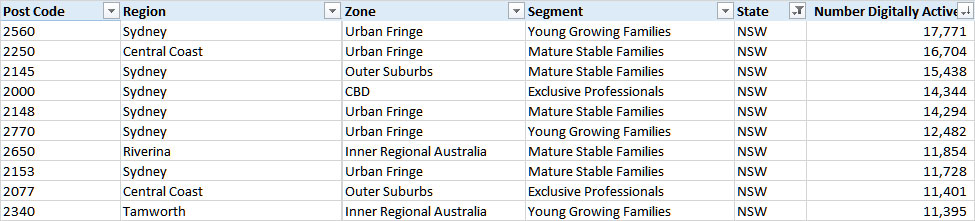

Here is the top 10 listing by number of digitally aligned – mobile first – households in NSW. They vary by segment, age, zone and region.

Here is the top 10 listing by number of digitally aligned – mobile first – households in NSW. They vary by segment, age, zone and region.

This information is useful to anyone wishing to engage with these households because it highlights where the centre of gravity for online initiatives should be focussed. The point is that although households are in the digital world, they still have a geographic centre. Digital still has a geographic sense.

This information is useful to anyone wishing to engage with these households because it highlights where the centre of gravity for online initiatives should be focussed. The point is that although households are in the digital world, they still have a geographic centre. Digital still has a geographic sense.

Looking at the banks, it seems that they are not heeding the geographic concentration of mobile first households, and nor are they fully comprehending the changes afoot. We think it likely there will be significant stranded costs in the branch network, and insufficient focus on “mobile first”banking offerings.

Households are leading the way.

Next time we will look at the state of play in Brisbane and subsequently explore developments in other regions, before revealing the top ten digital suburbs in Australia.