Recently the RBA has been talking about house price metrics, and in their recent outings have been downplaying data from CoreLogic preferring metrics from other sources. Was this a case of selecting the data which best fits with your world view? As we said at the time:

Housing is Australia’s largest asset class, worth an estimated $6.7 trillion, so it’s important to measure the performance of this very important asset class in an accurate and timely manner. Recently there has been a lot more focus on the measurements of housing market performance, so it’s timely to provide a summary of the primary methods used for measuring housing market performance from a value/pricing perspective.

The complexities of property data

Before we go into the different measures, it’s worthwhile providing a brief refresher on property data which provides some background about why measuring housing market performance is a complex undertaking.

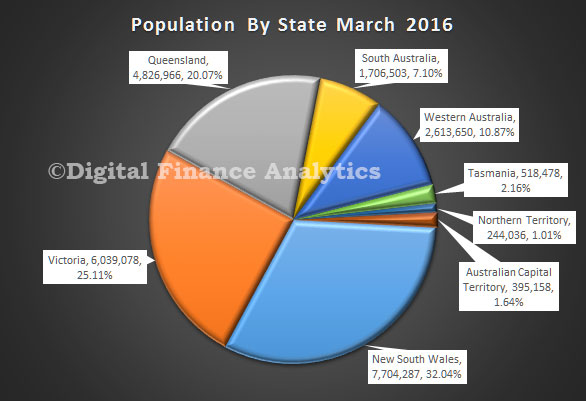

Firstly, compared with the equites markets, housing is an illiquid asset class. Individual properties are transacted, on average, every 8-10 years. The infrequency of transactions implies that the vast majority of residential properties are excluded from most housing market measurements which are reliant on transactional activity.

Secondly, housing is fundamentally nonhomogeneous; dwellings are unique in their characteristics based on their location and attributes, which makes the measurement of price and value shifts more challenging.

Additionally, the quality and timeliness of property data varies remarkably from state to state and between the private sector data providers. State governments collect a base level set of data which needs to be cleaned and augmented with more timely data and additional data sets such as attribute information to ensure a more complete and timely measure of housing markets is derived.

Regardless of the methodology used to measure dwelling price or value shifts, having housing data that is of the highest quality possible is the first and most important step in producing a reliable and accurate measure of the housing market.

CoreLogic collects and maintains the most comprehensive and current property and mortgage database, with more than 4.2 billion decision points across Australia and New Zealand that is growing in size every day. More than 60% of housing market transactions are collected directly from the industry, which provides a much more timely view of the housing market than relying solely on government provided transaction data.

What indicators are available to measure housing market conditions?

Housing market indices range in complexity from a simple median price indicators, which is subject to large amounts of bias and revision, through to a stratified median, repeat sales index and hedonic regression models. Each of these methods will provide different results for measuring price or value shifts across the housing markets.

Outside of these methodological differences, there will be further differences in results based on the data held by each of the private and public sector index providers as well as the way the data is cleaned, the sampling method, what geographic regions are being reported and what time frames the measures are reported across.

Simple median price

The median is simply the middle sales observation across a series of transactions. The median sale price is subject to a range of biases which can skew the middle observation up or down. Bias in median price can be caused by buyer types who are more active or less active in the market (for example, if first home buyers become more active there is likely to be a downwards bias in the median observation due to more transactions occurring at the affordable end of the pricing spectrum). Bias can also be found if there are changes in the types or quality of stock transacting and the median can be very volatile in markets with low turnover or where there are dramatic differences in the quality of housing. The advantage of median price is that it is very simple to compute and is easy to understand and interpret.

Simple median price measures are generally utilised by some of the real estate institutes and are still a common way of reporting price movements at the suburb or postcode level. Simple medians are useful for understanding what the middle observation for pricing is across a particular region over a specified point in time, however they aren’t all that useful for measuring capital gains over time due to the volatility and bias associated with this measure.

Stratified median

The stratified median measure, although still a measure of the middle observation, attempts to overcome the compositional bias of median price measures by dividing the market into separate strata’s, or segments, that are more alike. The Australian Bureau of Statistics, who use a stratified median measure, bases their stratification across dwelling types, the long term median price and socio economic indicators as specified here: . The ABS index is released quarterly after a significant lag and is non-revising.

Domain also use a stratified median approach, however no documentation appears to be publically available on their method or stratification approach. The Domain index is revisionary, however there is no transparency around the level of revision between quarters. Also, Domain do not appear to release their index results in a freely available format online.

The stratified median approach is a substantial improvement over the simple median for measuring price change across the housing market. As outlined in the simple median method, despite attempts to control for bias, the stratified median approach can be affected by changes in buyer activity or inactivity and by changes in the types or quality of dwellings that are transacting in the market.

It is important to note that non revising stratified median indices will not include off the plan sales data if the sale date has occurred more than three months prior to the reporting date. The reason for this is that such data tend to be quite lagged and reported by the Valuer General after settlement, which can occur several years after the sale date.

Repeat sales

A repeat sales index relies on identifying sales pairs and measuring the capital gain across these individual resales. The repeat sales method is very useful for measuring the demonstrated capital gain across individual properties that have resold, however the method excludes all transactions that don’t have a previous sale associated with the property. Inherently, the repeat sales method excludes new properties, which is a significant weakness at a time when a record amount of new housing stock is entering the market place. Additionally, the repeat sales index can be biased by property resales that have been affected by capital works (eg renovations and subdivisions) and can also be biased by properties that are transacted more frequently such as units and investment owned properties which generally have a higher turnover rate.

Residex (which is a CoreLogic owned company) publish a repeat sales index which is revisionary and released quarterly.

Off the plan sales are not accounted for in repeat sales indices as this methodology requires at least two sales for a property to make it eligible for inclusion.

Hedonic regression

The hedonic method of measuring housing market performance aims to track the true value shifts across the overall portfolio of housing, rather than price based movements based on observations of only those properties that have transacted. The hedonic imputation technique, which is used exclusively in Australia by CoreLogic, imputes the value of every Australian dwelling each day, taking into consideration every single data point we knew about the housing market at the point in time of calculation. Factors such as lot size, the number of bedrooms and bathrooms, car spaces and whether the home has a swimming pool or view are some of the hedonic attributes factored into the analysis. Based on a flow of around 1,400 new transactions received each day as well as a constant flow of new attribute data, our most accurate view of the imputed value of the property market is updated each day.

The benefits of a hedonic regression index include the sheer timeliness of the reading (virtually a real time indicator), the lack of any bias that can push the index higher or lower, as well as the fact that the index tracks true value shifts across the entire housing asset class rather than only across those properties that have recently transacted.

CoreLogic provides free public access to a full 12 month back series of the daily hedonic index, as well as a monthly summary of the end of month index results across each capital city by dwelling type. The index is published on the first working day of each month and has been independently peer reviewed and audited, the results of which are published on the CoreLogic web site, along with full documentation of the hedonic method used to build the index.

In summary, there are a variety of measures available to track dwelling prices and values across Australia. Each method presents its own pros and cons and there will always be differences in the results based on the different methods being uitlised, but also based on the differences in data quality, cleaning and sampling techniques, data timeliness, geographic context and time frames of the calculation. Other technical differences will also play out in the data based on specific ways each method treat the underlying data sets. For example, using a settlement date rather than a contact date in the analysis will show a difference in results, particularly at a time when a great deal of off the plan unit sales are flowing into the market where the difference between the contact date and settlement date could be several years.

While there will be divergence in these measurements of price and value changes from period to period, over a longer period, each of the methods used will tend to show broadly similar results. One notable exception is the presence of off the plan transactions, which will cause the hedonic index to diverge from repeat sales and non-revising median indices from time to time. Repeat sales indices and non-revising median indices (in particular based on sales data over the prior quarter) are more likely to broadly track one another because they both exclude off the plan sales.

CoreLogic privately calculates all of the indices described above, however our primary reference for measuring the change in house and unit values is the hedonic regression index thanks to the timeliness of the measure, the absence of any bias in the measurement and the fact that the index measures value growth across the entire housing portfolio rather than only those properties that have transacted.

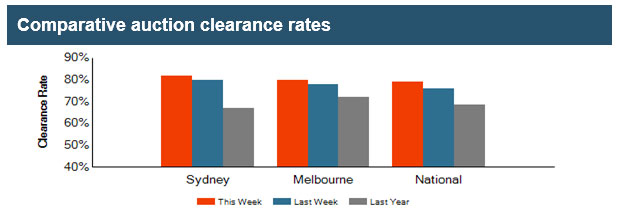

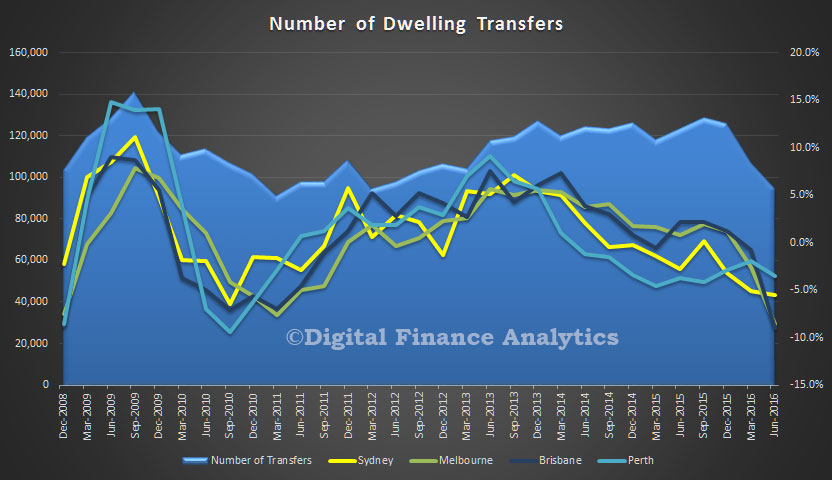

In order to get a complete understanding of the housing market there is a vast array of other housing market measures that need to be viewed in context with indices that measure price and value movements. CoreLogic also provides weekly updates on auction markets and clearance rates, private treaty metrics such as average selling time and vendor discounting rates, transaction numbers, listing counts and rental information as some examples.

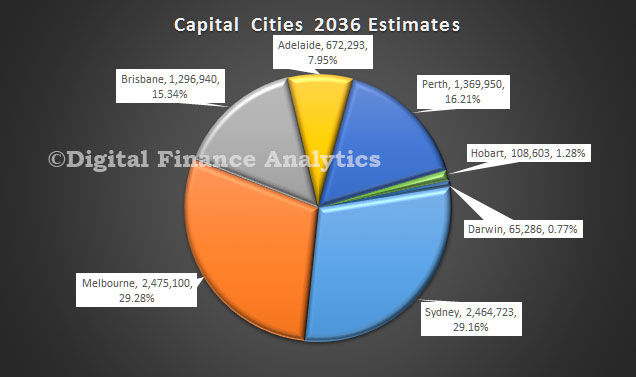

Additionally the performance of the housing market will vary substantially across the different product types and geographically, so it’s important to analyse the housing market at more granular levels than just capital city dwelling performance.

At CoreLogic, we place the utmost importance on our data and analytics assets. We dedicate more than $20 million each year in acquiring and maintaining our data sets. Our collection, analysis and research methods are audited regularly, and we are independent of any real estate, media or banking interests. CoreLogic continues to grow with over 480 people employed in ten locations in Australia and New Zealand. Over 20,000 customers and 150,000 end users in property, finance and government use CoreLogic services and platform more than 30,000 times a day.