The RBA minutes really tell us little more about the economy, but the did talk about household balance sheets.

“Growth in housing credit had continued to outpace growth in household incomes, which suggested that the risks associated with household balance sheets had been rising” .

See my highlights below.

Domestic Economic Conditions

Members commenced their discussion of domestic economic conditions by noting that inflation outcomes for the March quarter had been in line with forecasts presented in the February Statement on Monetary Policy. As such, the March quarter inflation data had generally increased confidence in the forecast that underlying inflation would pick up to around 2 per cent by early 2018. Both headline and underlying measures of inflation had been ½ per cent in the March quarter. In year-ended terms, headline inflation had been a little above 2 per cent and underlying inflation had increased to around 1¾ per cent. Higher petrol prices and the increase in tobacco excise had both made sizeable contributions to headline inflation; increases in tobacco excise were expected to continue adding to headline inflation over the forecast period. Members noted that the ABS would issue revised expenditure weights for the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the December quarter 2017 CPI release, which would reflect changes in consumption behaviour over the preceding six years in response to factors including large changes in relative prices.

Prices of tradable items (excluding volatile items) had been little changed in the March quarter but fell over the prior year. Strong competitive pressures in the retail sector had helped keep retail inflation low and there were signs that these pressures were affecting a broader range of consumer goods, such as furniture and household appliances. The appreciation of the exchange rate over the prior year is likely to have weighed on consumer prices.

Non-tradables inflation (excluding tobacco) had stabilised over preceding quarters. There had been signs of stronger price pressures in a few components, including an increase in new dwelling construction costs, which largely reflected a rise in the cost of materials. Utilities prices had also increased strongly in some cities in the March quarter, reflecting the pass-through to consumers of higher wholesale costs for gas and electricity. Members noted that utilities prices in other cities were likely to increase in the next few quarters and that there could be second-round effects on the CPI through upward pressure on business costs.

Working in the other direction, low wage growth and strong competition in the retail sector had contributed to domestic cost pressures remaining subdued. Rent inflation had remained persistently low and was around its lowest level in over 20 years, partly because rents had fallen significantly in Perth. Inflation in a range of administered prices, such as those for education, child care and pharmaceuticals, had been lower than usual, largely reflecting changes in government policy and the benchmarking of some administered prices to the CPI.

GDP growth over 2016 had been around 2½ per cent. Data that had become available over April suggested that the domestic economy had continued to expand at a moderate pace in the March quarter. Members noted that growth in domestic output was still expected to pick up to be a little above 3 per cent by the first half of 2018, as the drag from declining mining investment waned and as resource exports continued to pick up.

The impact of Cyclone Debbie had been most apparent in the spot price of coking coal, which had increased sharply after damage to key infrastructure affected coking coal exports from the Bowen Basin. Coking coal export volumes were expected to be significantly lower in the June quarter before returning to their previous levels over the remainder of 2017 as the damaged infrastructure is restored. Iron ore and liquefied natural gas exports were expected to make significant contributions to growth over the forecast period. Iron ore prices had fallen over the prior month, as had been expected for some time, and oil prices had been lower.

Although Australia’s terms of trade were expected to be higher in the near term than had been forecast at the time of the February Statement, much of the increase in the terms of trade since mid 2016 was expected to unwind over the next few years. As such, the recent rise in the terms of trade was not expected to result in materially more mining investment. However, members noted that the recent boost to mining profits could have other spillover effects, such as higher dividend payments, wage outcomes or government revenues, which represented an upside risk to the forecasts.

Recent data on retail sales growth and households’ perceptions of their personal finances suggested that consumption growth had moderated somewhat in early 2017. Further out, consumption was still forecast to expand at a bit above its average rate of recent years, consistent with the forecasts made at the time of the February Statement. Members noted that if the upside risks to household income growth from the higher terms of trade were realised, consumption growth could be stronger. On the other hand, if households were becoming more focused on paying down debt, this would imply some downside risks to the outlook for household consumption growth. A fall in housing prices could also weigh on consumption growth.

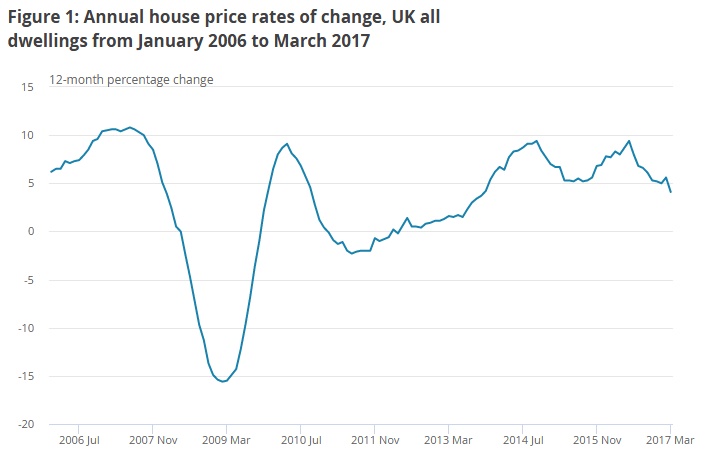

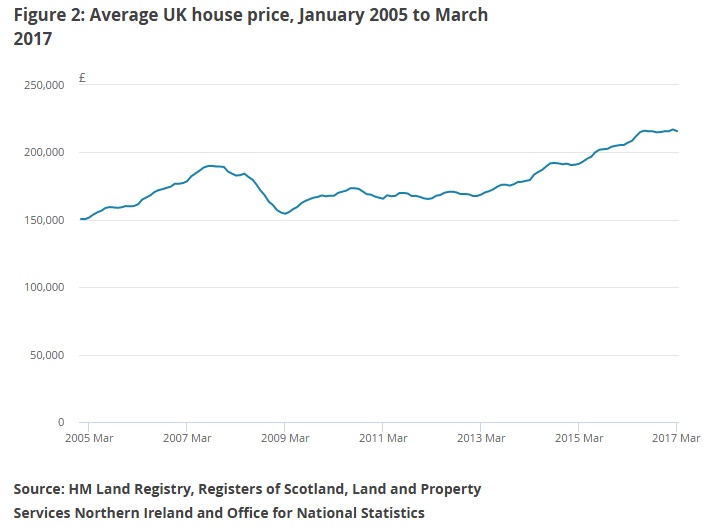

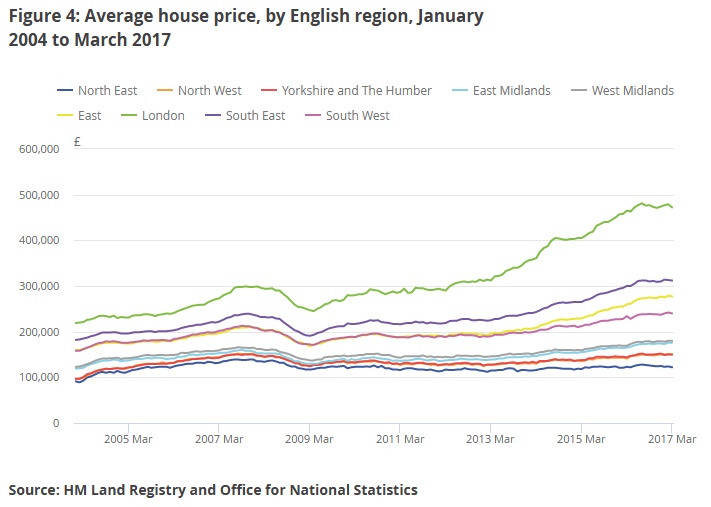

The large amount of residential construction still in progress was expected to support dwelling investment in the near term. Building approvals had been lower over prior months, particularly for higher-density dwellings, suggesting that this pipeline of construction work would continue to be worked off in coming quarters. Members noted that changes in the rate of home-building lag changes in population growth and that this had affected housing prices in some markets in the preceding few years. Growth in housing prices had remained brisk in Sydney and Melbourne, where population growth had been relatively strong, but had been weak in Perth, where population growth had fallen significantly following the end of the mining investment boom. At the same time, there had been some indications that the large increase in supply in the inner-city Melbourne and Brisbane apartment markets had weighed on prices, particularly in the case of Brisbane.

Members noted that surveys of business conditions had continued to improve and that some survey measures of investment intentions had picked up. However, other measures of investment intentions, including those recorded in the ABS capital expenditure survey, suggested that it could be some time before a stronger and more broadly based pick-up in non-mining business investment growth occurs. Other recent indicators of non-mining business investment, including non-residential building approvals and the pipeline of non-residential construction work, were still quite soft. The pipeline of outstanding public infrastructure work, however, had increased further.

Members observed that the unemployment rate had edged slightly higher in recent months to 5.9 per cent, but was expected to decline gradually over the forecast period. Members noted that this suggested spare capacity would remain in the labour market, although there was significant uncertainty about how to measure the degree of spare capacity, particularly given the higher levels of underemployment in recent years. An increase in labour demand could, in the first instance, be met partly by increasing hours worked by part-time employees, which would reduce measures of underemployment but represent an upside risk to the unemployment rate forecasts. The participation rate was slightly higher than had been forecast three months earlier and was assumed to remain around current levels throughout the forecast period.

Employment growth over the March quarter had increased and full-time employment had continued to rise. Members noted that this was in contrast to 2016, when all of the growth had been in part-time employment. Forward-looking indicators of labour demand, including data on vacancies and surveyed employment intentions, indicated that employment growth would pick up a little. Wage growth was expected to increase gradually as labour market conditions improved and the adjustment to the lower mining investment and terms of trade drew to an end.

Members had an in-depth discussion about changes in the composition of employment in recent decades. They discussed the implications of the secular upward trend in the share of part-time employment for labour market spare capacity. The share of part-time employment in Australia, which had increased from around 10 per cent in the early 1970s to over one-third at present, was relatively high by international standards, especially for younger workers; one driver is that students in Australia are more likely to combine their studies with part-time jobs. Data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey suggested that the majority of part-time workers worked part-time as a matter of choice given their personal circumstances, which vary across their lifecycle. People aged between 15 and 24 years are more likely to work part-time at the same time as studying, while a significant share of women between the ages of 25 and 44 years cite child-caring responsibilities as their main reason for working part-time. Furthermore, some older workers indicate a preference for working part-time, possibly as part of their transition to retirement. The survey also indicated that some part-time workers cite a lack of full-time opportunities or that their work requires part-time hours as the main reason for working part-time.

Members observed that growth in part-time employment had become more cyclical over time because businesses had been more able to respond to changes in demand by adjusting the hours worked by employees rather than the number of employees. This increase in labour market flexibility had been enabled by a range of factors including labour market deregulation, technological change and the shift towards a more service-based economy. As a result, the distinction between full-time and part-time work had become less important in assessing labour market conditions. In addition, understanding the degree of spare capacity in the economy required an assessment of the additional hours part-time workers were willing and able to contribute as well as the number of unemployed people.

International Economic Conditions

Members noted that GDP growth in Australia’s major trading partners had picked up since mid 2016 and most forecasters had revised up their outlook for global growth. Recent data had generally confirmed this improved outlook. The stronger activity had been evident in a pick-up in various indicators, including industrial production and measures of business and consumer sentiment, as well as in a broad-based rise in global trade. For some countries, including the United States, Japan and Korea, this had been reflected in an increase in the growth of business investment.

Economic growth in China had retained momentum in early 2017. Property construction and government spending on infrastructure had been among the important drivers of growth and had supported Chinese demand for Australian iron ore and coal as inputs into steel production. The share of investment in nominal GDP had fallen in recent years, while the share of consumption had been rising. Members observed that as economies matured, the share of services in consumption generally increased, which was consistent with the rising share of services in Chinese economic output. Risks around rapid housing price growth had remained a source of concern for the authorities and some ratcheting up of tightening measures had been needed to contain housing price inflation and speculative activity. Members noted that the outlook for the Chinese economy, particularly the residential property market, was an ongoing source of uncertainty for Australian exports and the terms of trade. Another source of uncertainty was how the Chinese authorities might balance achieving their growth targets with the risks associated with high and rising leverage in the Chinese economy.

In the United States, consumption growth had slowed in the March quarter, although this was likely to have been temporary. At the same time, there had been an increase in business investment growth, some of which was related to the energy sector. Survey measures had suggested that the prospects for further growth in business investment were favourable. The unemployment rate had fallen to a level consistent with full employment, while GDP growth was still expected to be above potential over the next couple of years.

Members noted that growth in the euro area was expected to continue at around its recent pace in early 2017. Business credit had increased since late 2016, having declined for a number of years, and the unemployment rate had fallen to its lowest level in nearly eight years. Members noted that the unemployment rate was particularly low in Germany, but had been persistently high in some other countries in the euro area, including France. The Japanese labour market had tightened further and economic growth had exceeded estimates of potential growth in Japan over recent years. Wage growth in Japan had increased a little, but core inflation had remained close to zero and inflation expectations were low.

Core inflation in the major advanced economies had generally remained low. Headline inflation had risen in recent quarters, but was likely to fall back because the effect of the earlier increase in oil prices had started to dissipate. Core inflation was expected to rise gradually in the major advanced economies as spare capacity in labour markets declined further.

Financial Markets

Members noted that financial markets had been relatively stable over recent months and global financial conditions generally remained very favourable. Heightened geopolitical tensions and various political developments had had little effect on financial markets.

Members noted that the widening of the yield spread between French government bonds and German Bunds ahead of the French presidential election had partly unwound following the result of the first round of voting. Members observed that long-term sovereign bond yields in the major markets had remained higher than in the preceding year, but were still low in a historical context.

The Bank of Japan left monetary policy unchanged at its April meeting, but stated that more quantitative easing would be undertaken if needed to reach the inflation target. The European Central Bank also left policy unchanged at its April meeting. Market participants did not expect the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to change monetary policy at its May meeting. Market expectations were for three increases in the federal funds rate by the end of 2018, compared with five increases implied by the median projections of FOMC members.

Chinese financial market conditions had tightened following the announcement of regulatory measures aimed at reducing leverage in financial markets. Short-term money market rates had risen and corporate bond financing had declined since the end of 2016.

Share prices in major markets had risen over the prior month and equity market valuations remained at high levels. Corporate bond yields generally remained very low, with spreads to government bonds having narrowed over the prior year. Corporate bond yields had mostly moved in line with sovereign bond yields over the prior month, except in China, where yields had increased following announcements by the authorities aimed at addressing high and rising leverage.

Members noted that the cost of borrowing US dollars in short-term foreign exchange swap and bank funding markets had declined from the high levels of 2016, reflecting both demand and supply factors.

There had been relatively little change in major exchange rates over the prior month. The Australian dollar had been little changed against the US dollar and on a trade-weighted basis over the prior month, but had depreciated slightly over the previous few months, which was consistent with the decline in commodity prices.

Australian government and corporate bond yields had generally moved in line with global bond markets over preceding months. Corporate bond issuance had remained relatively subdued, with resource-related corporations using their higher cash flows to reduce debt.

Australian share prices had increased a little over the prior month, with the exception of resource stocks, which had fallen in response to lower iron ore prices.

Members observed that housing credit growth had steadied in early 2017. Growth in investor housing credit had been rising for a time, but had stabilised in preceding months, consistent with the decline in loan approvals to investors. Household credit overall had grown at an annualised rate of 6 per cent over the six months to March. Variable housing interest rates had increased since late 2016, particularly for investors and interest-only lending. As a result, the average estimated interest rate on major banks’ outstanding housing lending had increased slightly, while the average cost of funding was estimated to have been little changed.

Financial market pricing indicated that market participants expected the cash rate to remain unchanged at the May meeting and over the remainder of the year.

Considerations for Monetary Policy

In considering the stance of monetary policy, members noted that the outlook for the global economy remained positive. The broad-based nature of the data supporting this outlook provided some confidence that the expansion could become self-reinforcing. At the same time, the improved conditions and ongoing accommodative stance of monetary policy globally had not, to date, led to a sustained increase in inflation. Members noted that various policy, financial and geopolitical risks to the ongoing expansion in the global economy were still present. The improvement in global economic conditions had helped to support commodity prices, although recent commodity price movements had also been affected by commodity-specific supply factors, such as disruptions to Australian coking coal exports following Cyclone Debbie.

Domestically, inflation outcomes had been as expected in the March quarter. The central forecast for headline inflation was that it would be above 2 per cent over the forecast period; underlying inflation was expected to increase gradually from its current rate of 1¾ per cent. Subdued growth in labour costs and strong competition in the retail sector had continued to have a dampening effect on aggregate inflation. Working in the other direction, rises in utilities prices and the cost of new dwelling construction had increased inflationary pressures.

Members noted that, although it seemed unlikely that wage growth would slow much further, wage pressures were expected to rise only gradually as the effects of structural adjustment following the mining investment and terms of trade boom, which had weighed on aggregate wage growth, continued to wane. Data on the labour market had been somewhat mixed, but forward-looking indicators continued to suggest that employment growth would maintain its recent pace and spare capacity in the labour market would decline gradually.

Recent data suggested that the Australian economy had grown at a moderate pace at the beginning of 2017. The outlook was little changed from three months earlier and continued to be supported by the increase in the terms of trade and the low level of interest rates, although lenders had announced increases in mortgage rates, particularly those paid by investors and on interest-only loans. The pick-up in non-mining business investment had been modest and forward-looking indicators of investment remained mixed. The drag from the fall in mining investment (and the spillover effects of this on non-mining investment and activity) had continued to ease. Recent data had provided further signs that the downswings in the Western Australian and Queensland economies were coming to an end. The depreciation of the exchange rate since 2013 had assisted the economy through this transition; an appreciation of the exchange rate would complicate this adjustment process.

Conditions in the housing market continued to vary considerably across the country. Conditions in established housing markets in Sydney and Melbourne remained robust, but housing prices had been falling in Perth. The additional supply of apartments scheduled to be completed over the next couple of years in the eastern capital cities was expected to put some downward pressure on growth in apartment prices and on rents, particularly in Brisbane.

Growth in housing credit had continued to outpace growth in household incomes, which suggested that the risks associated with household balance sheets had been rising. Recently announced supervisory measures were designed to help mitigate these risks by reinforcing prudent lending standards and ensuring that loan serviceability was appropriate for current financial and housing market conditions. However, it would take some time to assess the full effects of recent increases in mortgage rates and the additional supervisory focus.

The Board continued to judge that developments in the labour and housing markets warranted careful monitoring. Taking into account all the available information and the updated forecasts, the Board’s assessment was that maintaining the current accommodative stance of monetary policy would be consistent with achieving sustainable growth and the inflation target over time.

The Decision

The Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 1.5 per cent.