Payday Lending has been subject to considerable regulation in recent years, but using data from our household survey’s and DFA’s economic modelling, today we look at expected trends, in the light of the rise on convenient online access to this form of funding.

We will focus on analysis of small amount loan – a loan of up to $2,000 that must be repaid between 16 days and 1 year. ‘Short term’ loans of $2,000 or less repayed in 15 days or less have been banned since 1 March 2013. These rules do not apply to loans offered by Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions (ADIs) such as banks, building societies and credit unions, or to continuing credit contracts such as credit cards. More detail are on ASIC’s Smart Money site.

The law requires credit providers to verify the financial situation of applicants, and to ask for evidence from documents like payslips or Centrelink statements, copies of bills, copies of other credit contracts or statements of accounts or property rental statements. The number of documents a lender asks for will depend on whether they have relationship data, credit history or bank statements. If households receive the majority (50% of more) of income from Centrelink, the repayments on the small amount loan (including any other small amount loans held) must not exceed 20% of income. If they do, potential applicants will not qualify for a small amount loan.

From 1 July 2013, the fees and charges on a small amount loan have been capped. While the exact fee will vary depending on the amount of money borrowed, credit providers are only allowed to charge a one-off establishment fee of 20% of the amount loaned, a monthly account keeping fee of 4% of the amount loaned, a government fee or charge,default fees or charges and enforcement expenses. Credit providers are not allowed to charge interest on the loan. This cap on fees does not apply to loans offered by ADIs such as banks, building societies or credit unions.

DFA covered payday lending in a recent post, and ASIC has been highlighting a range of regulatory and compliance issues.

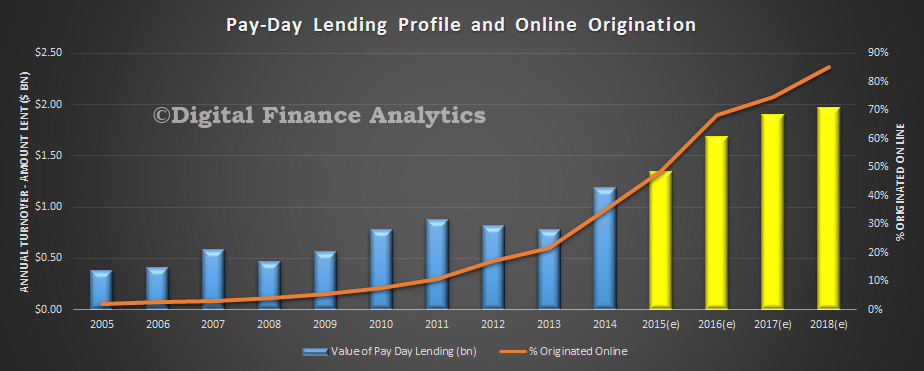

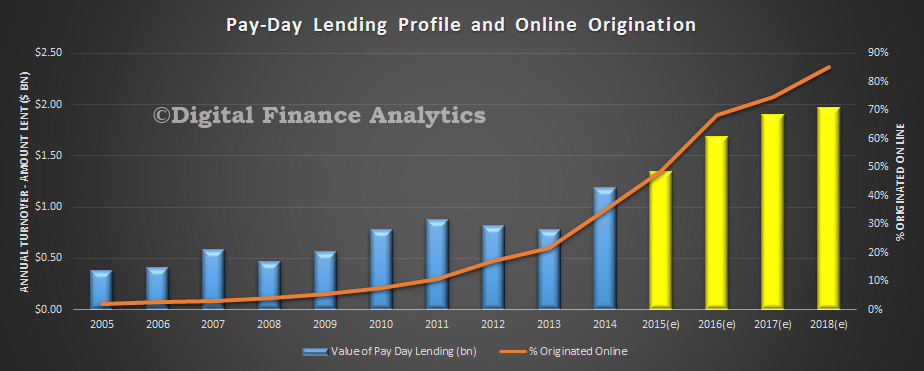

So, we begin our analysis with an estimation of the size of the market, and the proportion of loans originated online. The value of small loans made has been rising, and we now estimate the market to be more than $1bn per annum. We expect this to rise, and in our forward modelling we expect the market to grow to close to $2bn by 2018 in the current economic and regulatory context.

One of the main drivers of this expected lift is the rise in the number of online players, and the rising penetration of online devices used by consumers. Today, we estimate from our surveys about 40% of loans are online originated. We estimate that by 2018, more than 85% of all small loans will be originated online. As we highlighted in our previous post, the concept of instant application, and fast settlement is very compelling for some households.

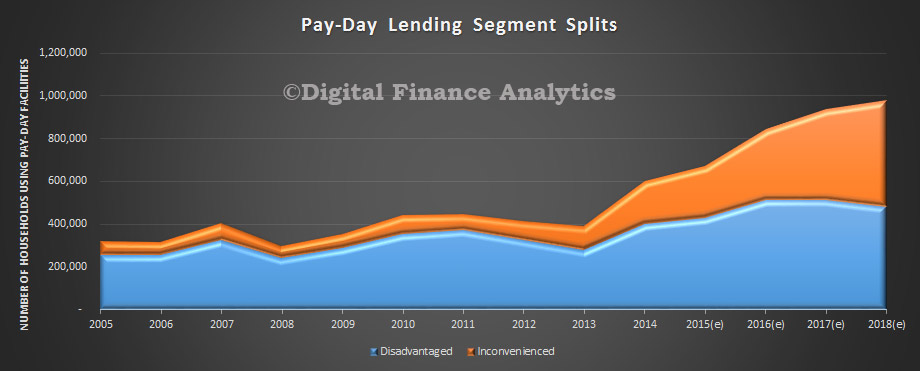

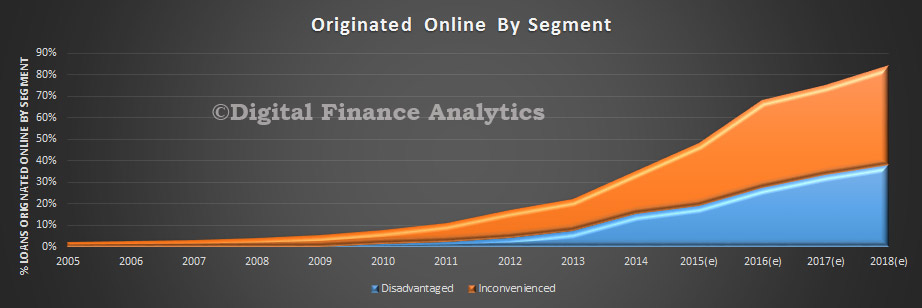

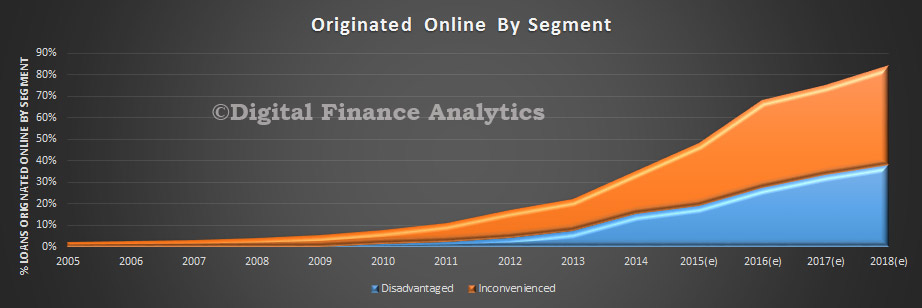

The DFA segmentation for payday households identifies two discrete segments. The first, which we call disadvantaged are households who are likely to be frequent users of small amount loans, often on Centrelink benefits, are socially disadvantaged, and with poor work history. The second segment is one which we call inconvenienced. These households are more likely to be in employment, but for various reasons are in a short term cash crisis. This may be because of unexpected bills, illness, unemployment, or some other external factor. They may even borrow for a holiday or family event such as wedding or funeral. They are less likely to be serial borrowers.

The DFA segmentation for payday households identifies two discrete segments. The first, which we call disadvantaged are households who are likely to be frequent users of small amount loans, often on Centrelink benefits, are socially disadvantaged, and with poor work history. The second segment is one which we call inconvenienced. These households are more likely to be in employment, but for various reasons are in a short term cash crisis. This may be because of unexpected bills, illness, unemployment, or some other external factor. They may even borrow for a holiday or family event such as wedding or funeral. They are less likely to be serial borrowers.

We see that both segments are tending to use online tools to seek a loan and may also be accessing other credit facilities. Our prediction is that by 2018, of the total of all small loans applied for, more than 35% will be applied for by disadvantaged, and 45% by inconvenienced via online. Together this means that as many as 90% of loans could be be sourced online. More than three quarters of these applications will be via a smart phone or tablet. As a result the average age of a small loan applicant is dropping, and we expect this to continue in coming years. This helps to explain the rise on TV and radio advertising, directing households with financial needs direct to a web site. Phone based origination, as a result is on the decline. We estimate there are more than 100 online credit providers in the market, comprising both local and international players. Online services means the credit providers are able to access the national market, whereas historically, many short terms loans were made locally by local providers, face to face. This is a significant and disruptive transformation.

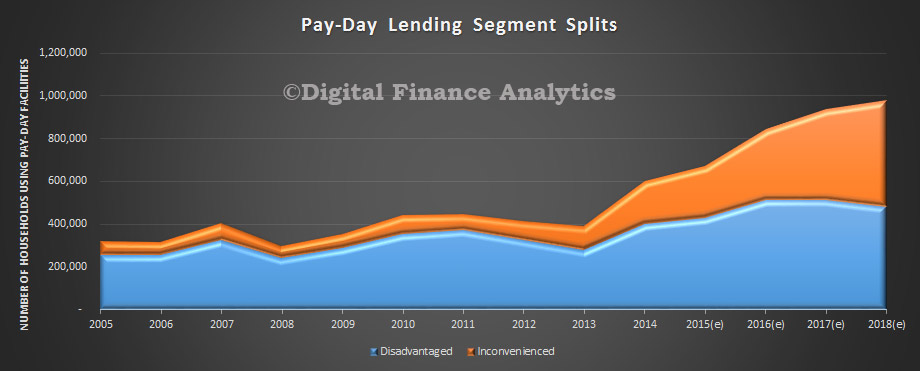

We finally look at the segment splits in terms of number of households using these loans. We note a significant rise in the number of inconvenienced households, to the point where by 2018, about half will be this segment. This is because the rules have been tightened for disadvantaged households, and online penetration for inconvenienced is higher.

We finally look at the segment splits in terms of number of households using these loans. We note a significant rise in the number of inconvenienced households, to the point where by 2018, about half will be this segment. This is because the rules have been tightened for disadvantaged households, and online penetration for inconvenienced is higher.