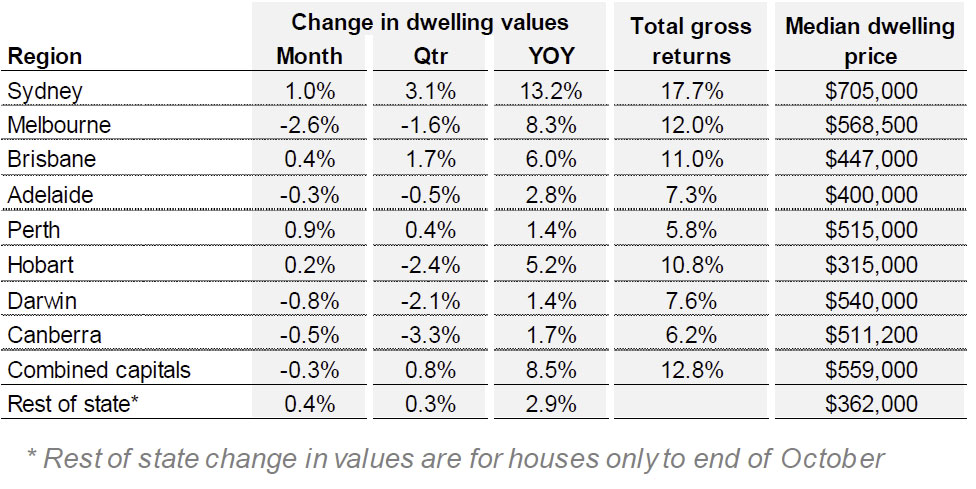

According to the November CoreLogic RP Data Home Value Index, dwelling values across Australia’s capital cities fell by -0.3 per cent over the month. The data highlights that the rate of home values growth continued to slow across the capital cities. Over the month, home values rose in Sydney (+1.0%), Brisbane (+0.4%), Perth (+0.9%) and Hobart (+0.2%) while values fell across the remaining capital cities. Over the three months, values increased in Sydney, Brisbane and Perth but fell across all other capital cities.

Author: Martin North

G20 On Financial Reform

The G20 Brisbane communique included a paragraph on financial stability reform, and refers specifically to the Financial Stability Review proposals to strengthen capital requirements for globally significantly banks.

Strengthening the resilience of the global economy and stability of the financial system are crucial to sustaining growth and development. We have delivered key aspects of the core commitments we made in response to the financial crisis. Our reforms to improve banks’ capital and liquidity positions and to make derivatives markets safer will reduce risks in the financial system. We welcome the Financial Stability Board (FSB) proposal as set out in the Annex requiring global systemically important banks to hold additional loss absorbing capacity that would further protect taxpayers if these banks fail. Progress has been made in delivering the shadow banking framework and we endorse an updated roadmap for further work. We have agreed to measures to dampen risk channels between banks and non – banks. But critical work remains to build a stronger, more resilient financial system. The task now is to finalise remaining elements of our policy framework and fully implement agreed financial regulatory reforms, while remaining alert to new risks. We call on regulatory authorities to make further concrete progress in swiftly implementing the agreed G20 derivatives reforms. We encourage jurisdictions to defer to each other when it is justified, in line with the St Petersburg Declaration. We welcome the FSB’s plans to report on the implementation and effects of these reforms, and the FSB’s future priorities. We welcome the progress made to strengthen the orderliness and predictability of the sovereign debt restructuring process.

It is sometimes hard to read the meaning behind the words, but Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England made some important comments in a speech in Singapore on his way home from Brisbane.

Banks are now much more resilient. They have more capital, more liquidity and are less susceptible to procyclical spirals. Capital requirements for banks are much higher, as are risk weights and the quality of bank capital. In all, new capital requirements are at least seven times the pre-crisis standards for most banks. For globally systemic banks, they are more than ten times. Large internationally active banks are on course to meet the new requirements 4 years ahead of the 2019 deadline. Despite the scale of the changes, the aggregate shortfall of those banks that still have shortfalls was €15bn at end 2013, having been €115bn two years ago.

It is just as clear that banks’ liquidity positions before the crisis were precarious. Now, for the first time, global standards have been agreed to place requirements on the liquid asset buffers banks must hold and on the extent of maturity transformation in which they can engage. The rapid contagion during the crisis showed how the system magnified shocks. Two particular fault lines made the system procyclical.

First, banks were heavily exposed to movements in market prices and volatility around them, creating a cycle in which falls in prices caused banks to retrench and reduce their positions, leading to further falls in asset prices. That issue has been addressed through strengthening regulatory requirements on trading books – a move that has contributed to the share of banks’ assets accounted for by trading assets almost halving.

Second, banks and shadow banks were entwined in a dangerous funding spiral. Incredibly low initial margins on repo transactions facilitated the build-up of excessive leverage and maturity mismatches in shadow banks. The first wave of losses led banks to tighten margin requirements, effectively reducing financing available to the non-bank financial system, causing those institutions to deleverage through asset sales, driving a death spiral of falling asset prices and rising margin requirements.

Such dynamics have now been mitigated through agreed minimum haircuts for securities financing transactions and the net stable funding ratio for banks.

As the memory of the crisis fades, it will be ever more important to explain the benefits of reform to counter the fatalism. So let me take this opportunity to take stock of the benefits of reforms, both of those already agreed and of the next phase of reform I have outlined. While we all recognise that future crises can never be ruled out, the steps taken to make banks safer and simpler have certainly reduced the likely frequency and severity of future financial crises. In doing so, they have reduced the exorbitant costs of instability. The Basel Committee assessed in 2010 that the economic cost of the median financial crisis amounted, over time, to 60% of national income. With a 5% probability of a crisis each year, that is equivalent to annual costs of 3% of GDP. For the G20 as a whole that is $2trn. By eroding these costs, financial reform alone can therefore more than deliver the G20 commitment to raise GDP by more than 2%. The Basel Committee found these costs to be minimised only if risk-weighted bank capital ratios were raised above 15%. The Basel III requirements did not go this far, in part because they anticipated the additional requirements for loss absorbing capacity that G20 Leaders have just endorsed.

Once implemented, the combined effects of the reforms will take the system much closer to the degree of safety needed to minimise the costs of financial crises. That authorities have reached this point in a measured way – allowing both equity and forms of debt to qualify as loss absorbing capacity – shows our sensitivity to the potential costs of greater safety. What are those costs? Three points are worth emphasising.

First, the Basel Committee study judged that each 1% increase in capital ratios could reduce output by just 0.1% as higher bank funding costs were passed through to borrowers. However, even that small number seems an upper bound. It fails to take account of the fact that monetary policy can offset the impact of higher lending spreads on effective borrowing rates.In fact, the need to offset the impact of higher lending spreads is one reason why some advanced economy central banks, such as the Bank of England, are so clear now that interest rate increases, when they come,will be gradual and limited.

Second, the transitional costs of moving to higher capital requirements were found to be a little higher than the long-run costs. But that result depends on the starting position. Outside of financial booms, under capitalised banking systems do not provide the credit needed for economic growth, regardless of capital requirements.Where banking systems have raised capital and restored trust in their creditworthiness, access to credit has returned. This central lesson from the US and the UK recoveries could not be clearer. The evidence internationally suggests much the same. With the possible exception of parts of the euro area, lending spreads have fallen and credit volumes have increased at the same time as capital has gone up. In other words, if anything, regulators may have significantly overestimated the transitional costs, or even possibly got the sign wrong.

Third, although tighter regulatory requirements have caused bank balance sheets to shrink, that does not translate fully into reduced access to credit for real economy borrowers. As I said, some of the reduction in bank-based intermediation has been substituted with market-based finance for the real economy. Moreover,as bank balance sheets have shrunk, and as they have rebalanced more towards traditional banking than trading, they have become more focussed on the real economy.

In short, any serious look at the experience of post-crisis reform shows that reform and regulation support –not damage – long-term prosperity.Furthermore, the reforms have also brought benefits in terms of the distribution of the costs and benefits of finance. The removal of the implicit taxpayer subsidy transfers the costs of excessive risk taking to private creditors and away from the taxpayer.And by making resolution of failing institutions a real possibility and facilitating smooth exit, the reforms willalso promote competition. Before the crisis, the largest and most systemic firms enjoyed the largest subsidies. Now, over time, the absence of that subsidy will create a level playing field, transferring the benefits of finance to customers and clients.These benefits will accrue slowly over time. Indeed, they may never be obvious to many who don’t recall a different world. That is why it is vital that our sons and daughters are taught not that financial crises are inevitable, but that they are both avoidable and tremendously costly for jobs, growth and prosperity. The lessons of the crisis need to be learned and handed down to future generations in order that the next phase of reform is sustained.Those reforms have the potential to make finance more effective in serving the real economy

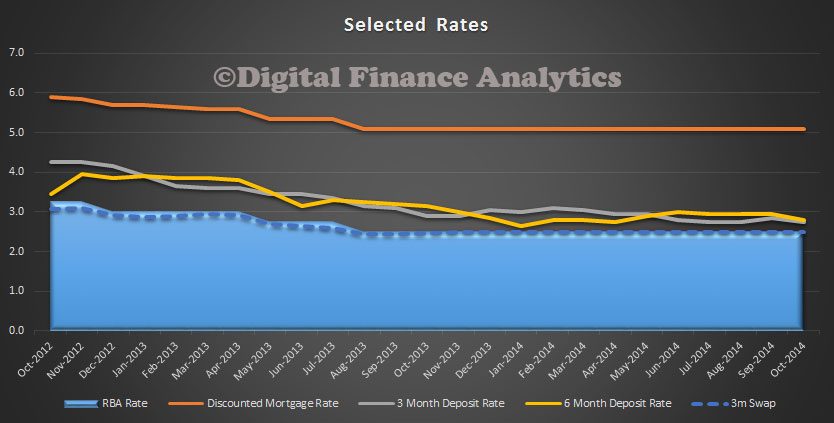

Savers Are Going To Get Crunched

There is bad news for those households with bank deposits. We have already seem a range of deposit repricing initiates by the banks, as they trim their deposit rates. But it is likely to get worst, as international sources of funding get cheaper, and changes to capital requirements are likely to translate to further rate cuts for savers down the track.

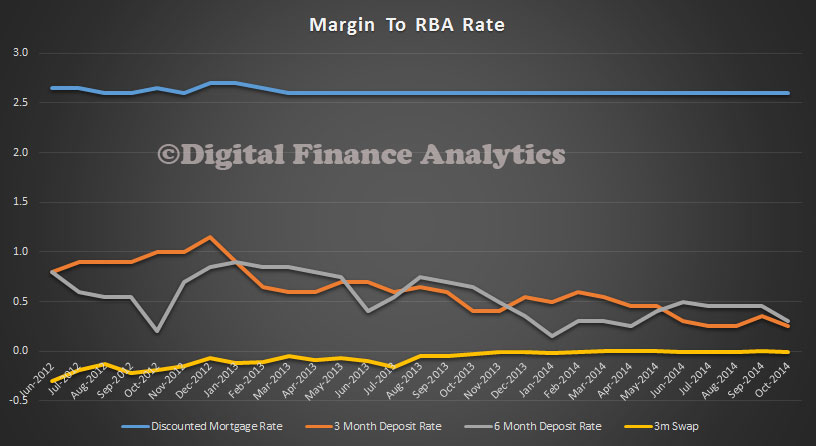

Rates have been coming down for those with bank deposits in recent months, and the rate of fall has accelerated recently. The chart below shows the movements of discounted mortgages, 3 month and 6 month deposits, and also the 3m swap rate, using RBA datsets.

Whilst there is selective deeper discounting on the mortgage side, for some, savers are finding their returns falling. This is show most clearly by comparing the margins between the RBA rate, and loans and deposits. Despite the static RBA rate, deposit rates are falling.

Whilst there is selective deeper discounting on the mortgage side, for some, savers are finding their returns falling. This is show most clearly by comparing the margins between the RBA rate, and loans and deposits. Despite the static RBA rate, deposit rates are falling.

We know that overseas funding continues to improve, and as a result banks will be seeking to source funds through these channels. They are also discounting hard to get mortgage business. So to square the circle they are quietly trimming the rates to savers. We highlighted last week that bank deposits fell by 0.06% last month, to a value of $1.76 trillion, whereas lending grew.

We know that overseas funding continues to improve, and as a result banks will be seeking to source funds through these channels. They are also discounting hard to get mortgage business. So to square the circle they are quietly trimming the rates to savers. We highlighted last week that bank deposits fell by 0.06% last month, to a value of $1.76 trillion, whereas lending grew.

Looking ahead, with banks likely to have their wings clipped by the FSI report, due soon, and changes to capital following on which are likely to lift the costs of lending, the net result will be further pressure on saving rates, and more households looking for higher risk alternatives, as the RBA often mentions in their monthly statements. This continued fall of deposit returns hits older household segments the hardest, especially those banking on deposits to fund their retirements. Returns will be below inflation, so capital is effectively being eroded.

As a comparison, in the UK they have had 6 years of low deposits, and recently savers have found their rates being cut further. Many households are in financial stress as a result. In Australia, savers will either wear the losses, seek higher risk alternatives, or spend the money. Perhaps this latter course may assist an otherwise sluggish consumer sector. But it is not looking pretty.

Higher Capital for Big 4 Australian Banks Credit Positive – Fitch

According to Fitch Ratings, the Australian Banks will be able to handle any potential increase in capital requirements, and would be credit positive for the banks.

Australia’s Financial System Inquiry (FSI), due to report by end-2014, is likely to recommend higher capital requirements for the large banks, says Fitch Ratings. A higher capital charge and/or a rise to the mortgage risk-weighting floor for the four domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs) are the most likely ways in which this will be implemented. In either case, Fitch maintains that Australia’s banks are well positioned to meet the additional buffers though internal capital generation.

Australia’s bank capital profiles have strengthened since 2008, though they are about average relative to their international peers. Fitch maintains that additional capital requirements for the four D-SIBs – ANZ, CBA, NAB and Westpac – would be credit positive.

The FSI, led by Chairman David Murray, is expected to push for regulatory changes that would reinforce the improvements in recent years. The gap between Australia’s banks and global peers in terms of capital strength has closed, though an objective of the FSI is to bring the largest banks back into the upper quartile. Increasing the D-SIB capital buffer requirement from the current 1ppt, as well as implementing a mortgage risk-weight floor for banks using advanced models to calculate regulatory capital, are likely to be two areas of focus for the Murray report.

A number of global initiatives are addressing the wide discrepancy in risk weights based on banks’ internal models, including a Basel Committee project. Risk-weights for residential mortgages have been a particular focus because they can be very low. In Sweden, the risk-weight floor for residential mortgages was raised to 25% from 15% this year, while Norway is raising its floor to 20%-25% from 10%-20%. In Switzerland, the authorities are reviewing the differences between risk-weights based on banks’ internal models and those based on the standard approach used by domestic and regional banks.

Taking the global context into account, there is the potential for the FSI to recommend raising Australia’s mortgage risk-weight floor to 25%, which would result in capital shortfalls for each of the four major banks – AUD2.9bn for ANZ (the lowest) to in excess of AUD4.6bn for Westpac, based on FY14 numbers and assuming the banks maintain an internal buffer of 1ppt over the fully loaded regulatory requirements. Under a more aggressive scenario, where the risk-weight floor is increased to 30%, the D-SIB charge also raised 2ppt to 3ppt, and a 1ppt internal buffer maintained, the capital shortfalls would be between AUD12bn-15bn for each of the Big 4, and total around AUD53bn. With combined profits for the four banks of around AUD29bn in FY14, the capital shortfall under this scenario would be just less than twice annual profit before dividend.

The Basel Committee’s framework for D-SIBs is more flexible and less prescriptive than the G-SIB framework that applies to the world’s largest banks, but the phase-in for both starts in 2016. Few jurisdictions have yet finalised their D-SIB implementation, but the current 1ppt requirement in Australia appears low compared with Sweden, where a systemic risk buffer of 3ppt is required from 1 January 2015, with a further 2ppt within Pillar 2. Hong Kong, Singapore and India are considering D-SIB buffers of up to 2.5ppt, 2.0ppt and 0.8ppt, respectively, although these have not necessarily been finalised.

Fitch expects that the Australian authorities would set implementation timetables so that the banks would be able to generate the bulk of capital internally, even under the latter scenario.

Increasing the capital of the Big 4 would continue the trend for credit profile strengthening that has occurred since 2008 at a time when there are concerns about risks from rising property prices and exposure to a slowing China and commodity cycle. However, competitively, the higher D-SIB charges and risk-weight floors for the Big 4 could erode some of their substantial scale advantages relative to smaller competitors.

It is important to note that if the measures to address the problems of ‘too big to fail’ banks went beyond higher capital requirements and included measures such as ‘bail-in’ of senior creditors, this would be likely to result in downgrades of Fitch’s Support Ratings and Support Rating Floors – the agency currently factors in a very high likelihood of government support for the major banks, given their strong market position in the domestic banking system. The Issuer Default Ratings, however, would be unaffected, as no Australian bank is currently at its Support Rating Floor.

Housing Lending Above $1.4 trillion

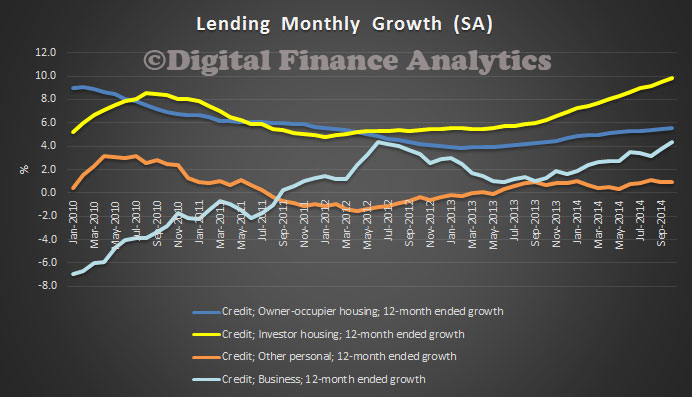

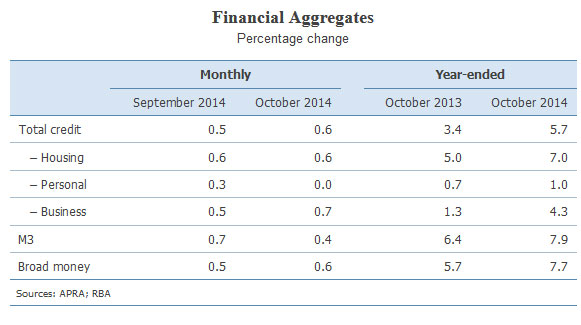

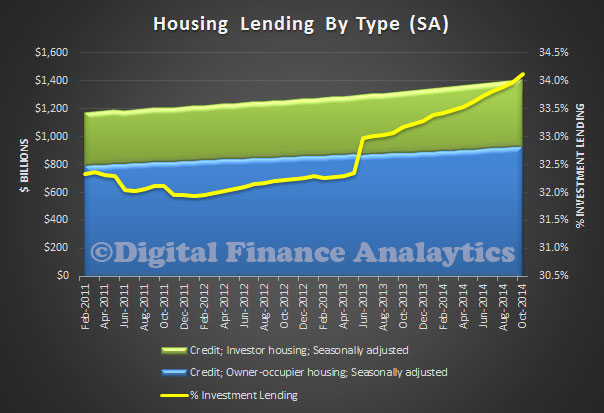

The RBA statistics released today reveals that housing lending has now reached a new milestone, overall reaching $1.4 trillion.In seasonally adjusted terms, owner occupied housing grew 0.44% and investment lending 0.99%. Investment lending accounted for more than 34% of all loans, a record (and is understated because owner occupied lending includes refinancing). Overall it is likely more new investment loans than owner occupied loans were written in the month. We will need to wait for the detailed figures to confirm this.

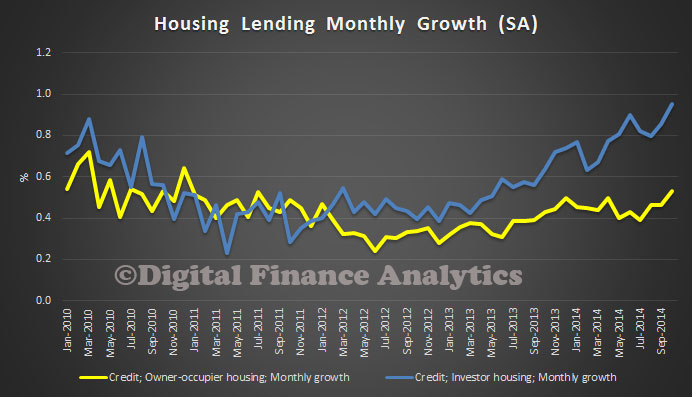

Looking at the monthly growth data, we see the continued relative momentum in investment lending, and this underscores the concerns of the OECD and other observers.

Looking at the monthly growth data, we see the continued relative momentum in investment lending, and this underscores the concerns of the OECD and other observers.

In 12 month terms, housing lending grew 7%, Personal Credit by 1.0% and business credit grew 4.3%.

In 12 month terms, housing lending grew 7%, Personal Credit by 1.0% and business credit grew 4.3%.

Investment Lending Burns Bright

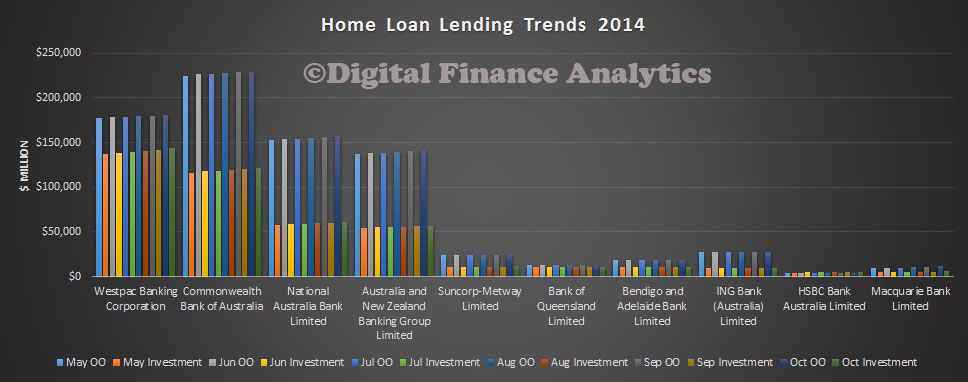

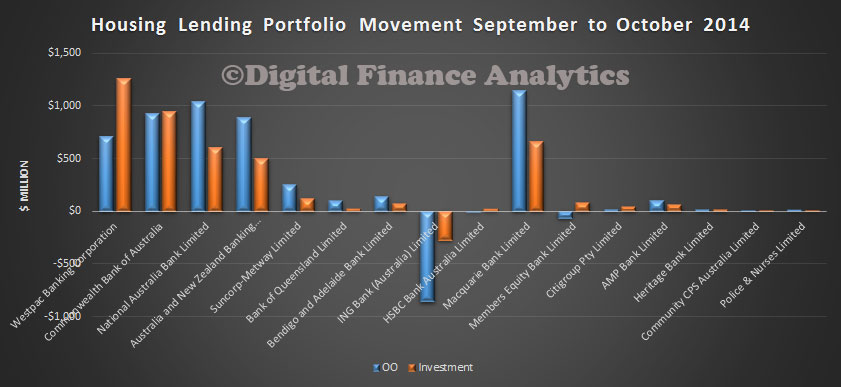

APRA released their monthly banking statistics for October 2014 today. The total value of housing lending rose to $1.298 trillion, from $1.288 in September, up 0.81%. Of this however, Investment lending rose 1.03% by $4.59 billion and Owner Occupied Lending rose 0.69% by $5.79 billion. This data relates the the banks (ADI’s) excluding the non-bank sector. This is normally about $110 billion.

Looking in detail at the bank by banks analysis, we see a familiar set of trends.

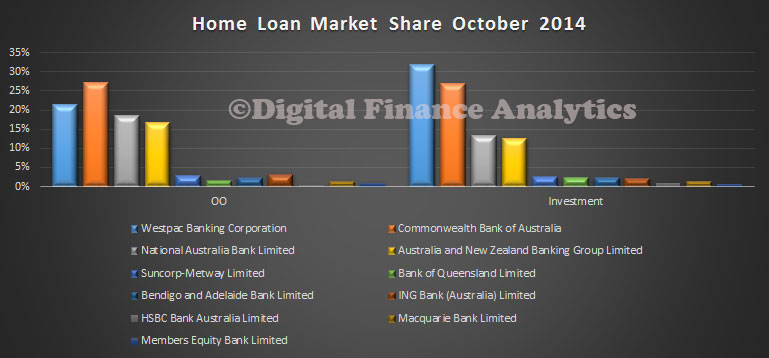

Westpac leads the pack on investment mortgage lending, with a 31.8% share, whilst CBA leads with owner occupied lending with 27.1% share.

Westpac leads the pack on investment mortgage lending, with a 31.8% share, whilst CBA leads with owner occupied lending with 27.1% share.

Looking at the movements, only ING Bank recorded a fall in value in their portfolio. Macquarie grew the strongest. This relates to the $1.5 billion portfolio of non-branded mortgages they purchased from ING in September.

Looking at the movements, only ING Bank recorded a fall in value in their portfolio. Macquarie grew the strongest. This relates to the $1.5 billion portfolio of non-branded mortgages they purchased from ING in September.

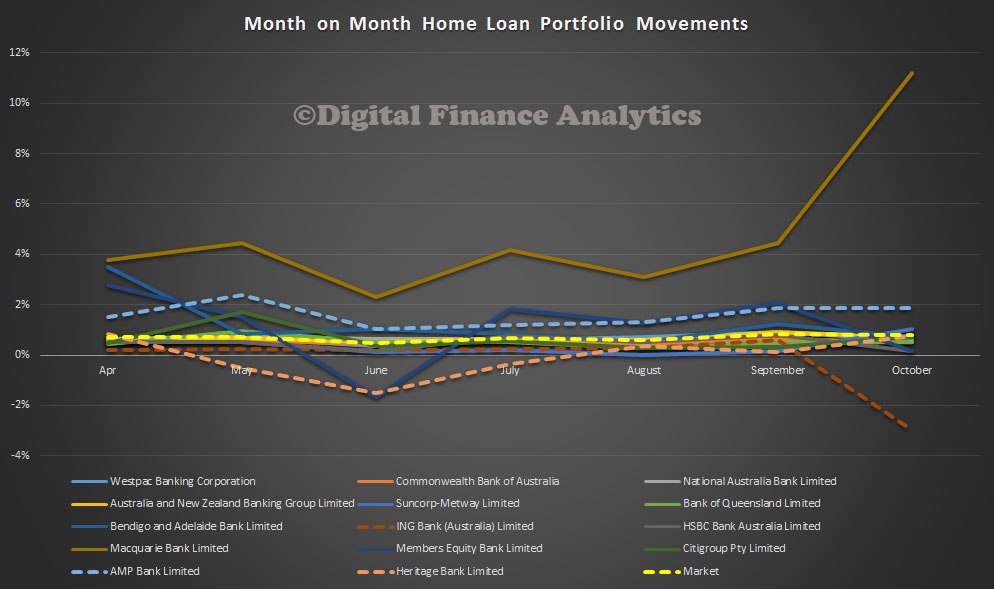

Looking in percentage terms, we see that Macquarie and AMP grew well above system, and ING below in October.

Looking in percentage terms, we see that Macquarie and AMP grew well above system, and ING below in October.

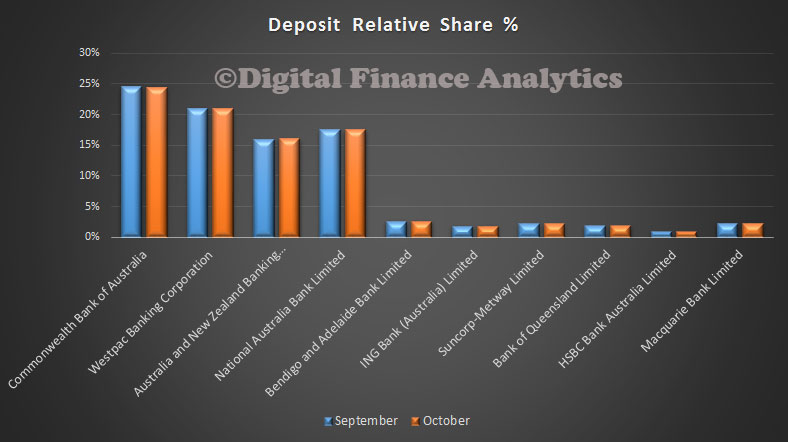

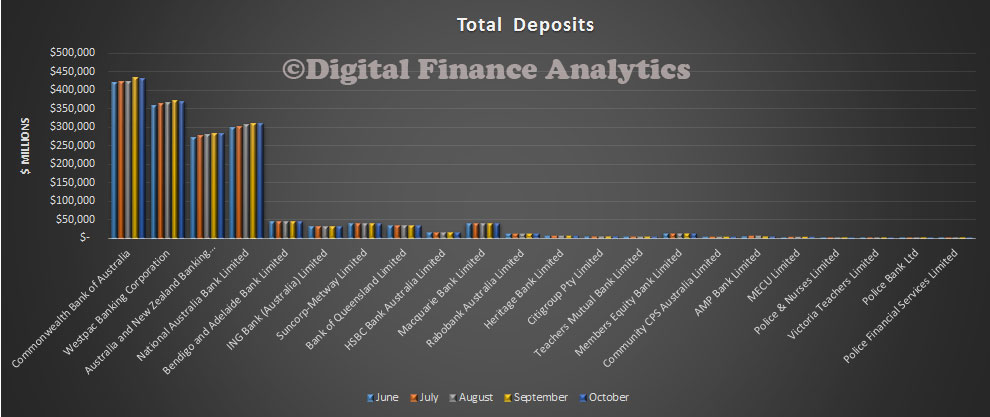

Turning to deposits, they fell by 0.06% in the month, to a value of $1.76 trillion. There was little movement between players, though given the growth in loans above, it is clear that wholesale funding is being accessed now, and this explains the continued fall in deposit interest rates.

Turning to deposits, they fell by 0.06% in the month, to a value of $1.76 trillion. There was little movement between players, though given the growth in loans above, it is clear that wholesale funding is being accessed now, and this explains the continued fall in deposit interest rates.

CBA maintains its position as the largest deposit holder, with 24.5% of the market.

CBA maintains its position as the largest deposit holder, with 24.5% of the market.

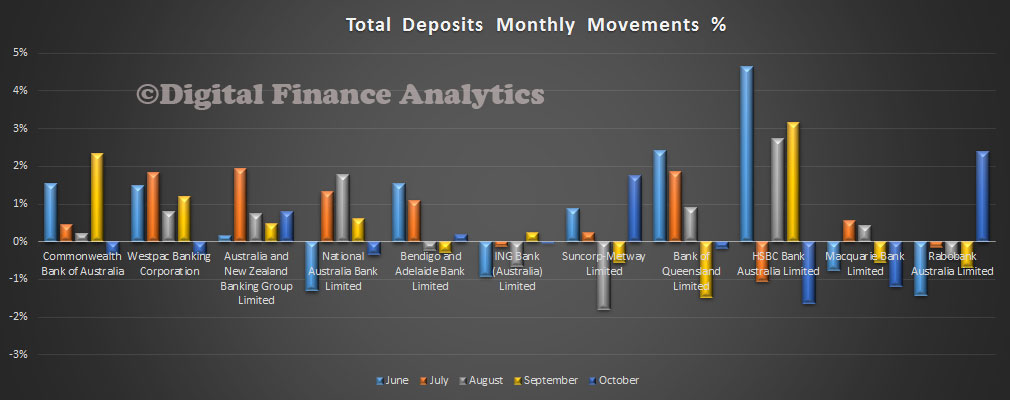

Looking at movements, we see Rabobank growing their deposits in percentage terms the strongest in the month, a reversal from previous recent months. Other than ANZ, the majors all lost a little share. Suncorp grew its book also.

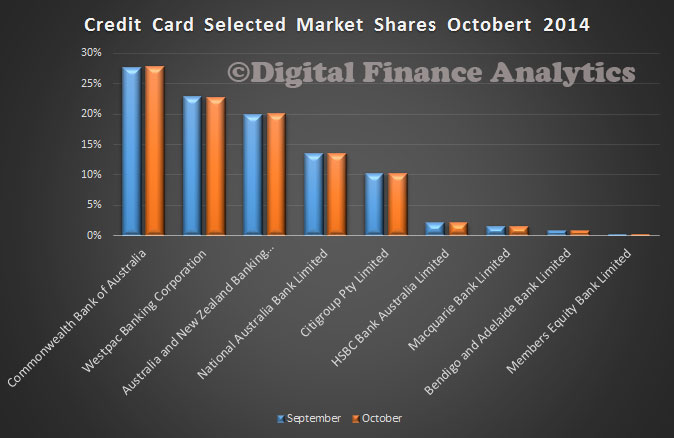

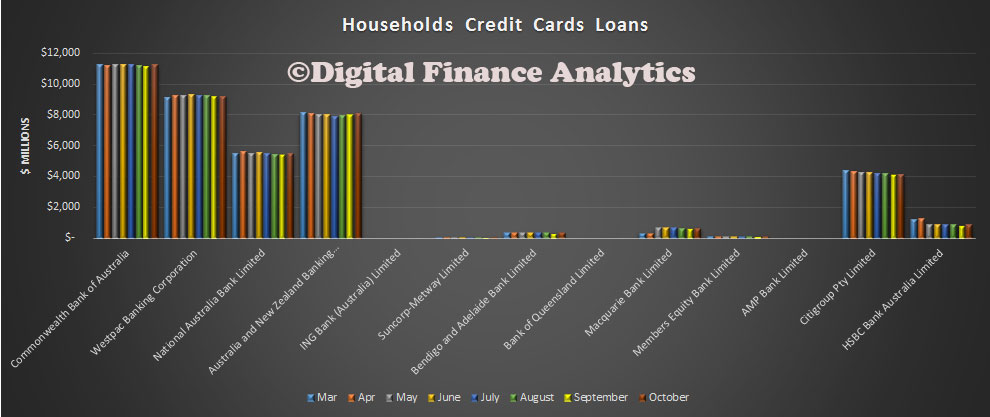

In cards, balances rose by about $50 million, to $40.4 billion.

In cards, balances rose by about $50 million, to $40.4 billion.

CBA continues to hold the largest cards share with 27.8% of the market.

CBA continues to hold the largest cards share with 27.8% of the market.

Banks And Their Capital

APRA today published the quarterly ADI performance statistics to September 2014.

Over the year ending 30 September 2014, ADIs recorded net profit after tax of $33.5 billion. This is an increase of $3.6 billion (12.0 per cent) on the year ending 30 September 2013.

As at 30 September 2014, the total assets of ADIs were $4.2 trillion, an increase of $345.0 billion (9.1 per cent) over the year. The total capital base of ADIs was $210.4 billion at 30 September 2014 and risk-weighted assets were $1.7 trillion at that date. The capital adequacy ratio for all ADIs was 12.4 per cent.

Impaired assets and past due items were $29.1 billion, a decrease of $7.4 billion (20.3 per cent) over the year. Total provisions were $16.6 billion, a decrease of $6.1 billion (26.9 per cent) over the year.

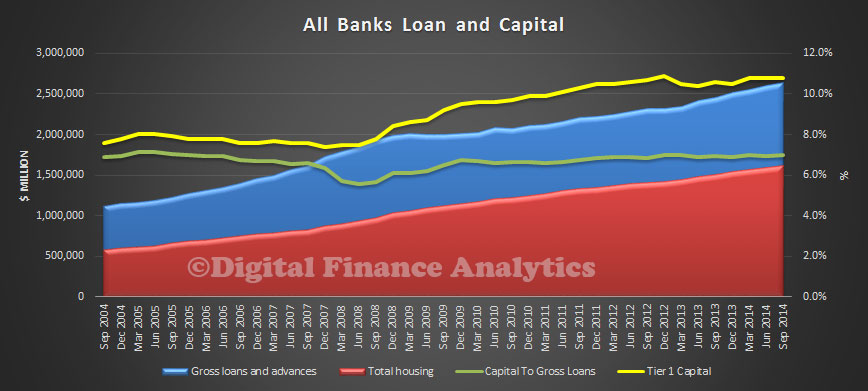

We have been looking at the relative capital positions of the banks, highly relevant in the current climate where we expect the FSI inquiry report to be commenting on this, as well as the current regulatory reviews, globally and locally.

So we have taken the All Bank data and compared the Tier 1 capital ratio (the yellow line) with a plot of the ratio of lending to capital held. Because the mix of loans has changed, with a greater proportion relating to lending for housing, and the fact that these loans have lower capital weighting, the reported Tier 1 capital is significantly better than the true, unweighted position. In fact, banks are holding relatively less capital against their loan books now compared with before the GFC. This is one reason why capital ratios are under review.

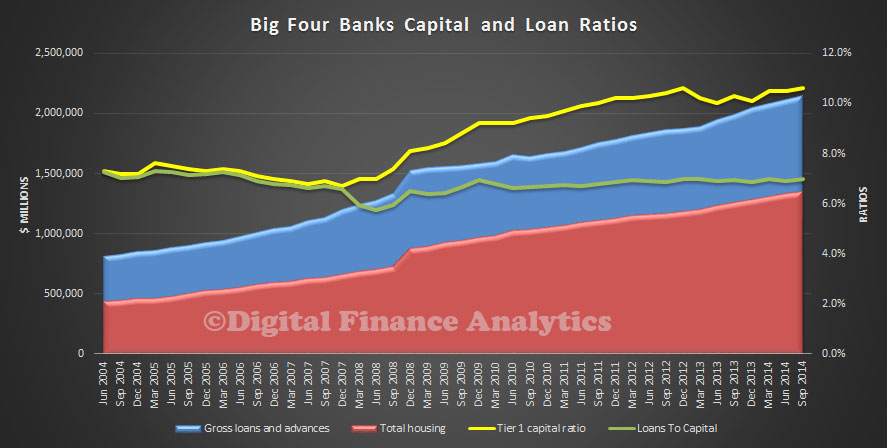

Now, if we look only at the APRA data for the big four banks, we see an even wider divergence, enabled by the advanced capital calculations which enable these banks to hold even less capital against certain housing loan categories. This places the major banks at a competitive pricing advantage.

Now, if we look only at the APRA data for the big four banks, we see an even wider divergence, enabled by the advanced capital calculations which enable these banks to hold even less capital against certain housing loan categories. This places the major banks at a competitive pricing advantage.

Almost certainly, the majors will be required, in due course to hold more capital, and this may tilt the playing field towards some of the smaller players. It may also mean lower returns of deposit accounts, and and reduced loan discounting. Overall profitability for some players will also be tested, though we believe there is plenty of slack in the system currently.

Almost certainly, the majors will be required, in due course to hold more capital, and this may tilt the playing field towards some of the smaller players. It may also mean lower returns of deposit accounts, and and reduced loan discounting. Overall profitability for some players will also be tested, though we believe there is plenty of slack in the system currently.

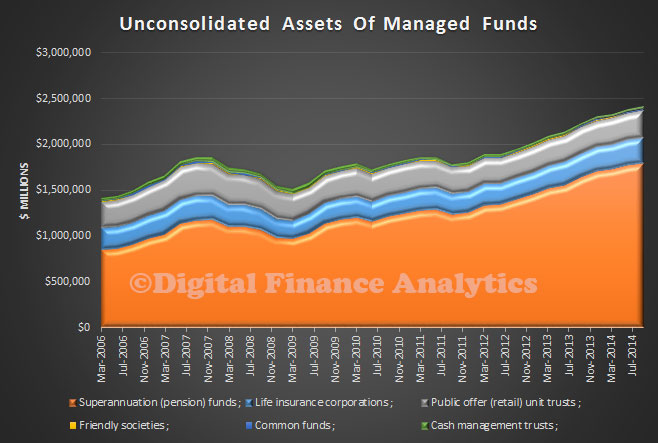

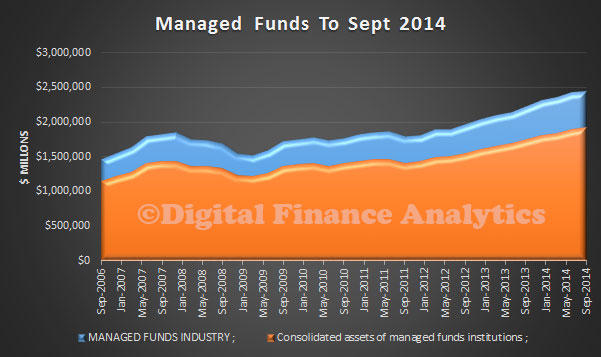

Managed Funds Now Worth $2.44 Trillion

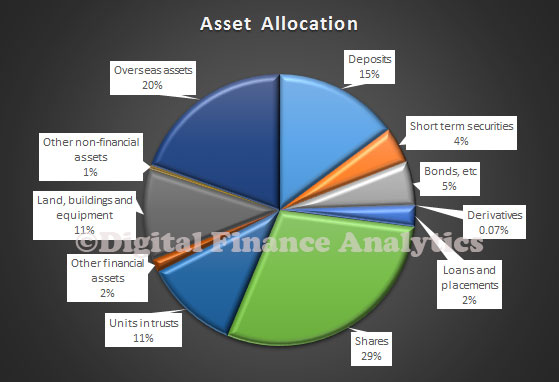

The ABS just released their Managed Funds data to September 2014. The managed funds industry had $2,439.5b funds under management, an increase of $26.6b (1%) on the June quarter 2014 figure of $2,412.8b. The main valuation effects that occurred during the September quarter 2014 were as follows: the S&P/ASX 200 decreased 1.9%; the price of foreign shares, as represented by the MSCI World Index excluding Australia, increased 2.4%; and the A$ depreciated 7.6% against the US$.

The consolidated assets of managed funds institutions were $1,922.7b, an increase of $20.0b (1%) on the June quarter 2014 figure of $1,902.7b. The asset types that increased were overseas assets, $16.8b (5%); deposits, $4.4b (2%); short term securities, $2.5b (3%); units in trusts, $2.3b (1%); land, buildings and equipment, $0.6b (0%); and shares, $0.1b (0%). These were partially offset by decreases in other financial assets, $5.8b (16%); bonds, etc., $0.5b (0%); other non-financial assets, $0.2b (2%); and loans and placements, $0.2b (0%). Derivatives were flat. There were $484.7b of assets cross invested between managed funds institutions.

The consolidated assets of managed funds institutions were $1,922.7b, an increase of $20.0b (1%) on the June quarter 2014 figure of $1,902.7b. The asset types that increased were overseas assets, $16.8b (5%); deposits, $4.4b (2%); short term securities, $2.5b (3%); units in trusts, $2.3b (1%); land, buildings and equipment, $0.6b (0%); and shares, $0.1b (0%). These were partially offset by decreases in other financial assets, $5.8b (16%); bonds, etc., $0.5b (0%); other non-financial assets, $0.2b (2%); and loans and placements, $0.2b (0%). Derivatives were flat. There were $484.7b of assets cross invested between managed funds institutions.

Unconsolidated assets of superannuation (pension) funds increased $24.3b (1%), life insurance corporations increased $3.0b (1%), public offer (retail) unit trusts increased $1.9b (1%), cash management trusts increased $0.6b (2%), common funds increased $0.2b (2%), and friendly societies increased $0.1b (1%).

Unconsolidated assets of superannuation (pension) funds increased $24.3b (1%), life insurance corporations increased $3.0b (1%), public offer (retail) unit trusts increased $1.9b (1%), cash management trusts increased $0.6b (2%), common funds increased $0.2b (2%), and friendly societies increased $0.1b (1%).

Foreign Property Purchase Rules To Be Enforced

The report on foreign property buyers is out, and the recommendations are significant, and the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) criticised.

The current framework relating to foreign purchases of Australian housing will be retained to encourage investment in new dwellings and increase housing supply. But there are a bunch of recommendations, which cover the bases quite well in terms of enforcement. First, there is the intent to creation of a national land title register to record the citizenship and residency status of real estate buyers. This means that data on residential status will be checked during purchase. Next, professionals involved in real estate transfers (such as lawyers, transfer agents, developers, real estate agents), and family members who knowingly assist foreign buyers to breach the rules will be fined. There would be greater data sharing between the Immigration Department and FIRB to detect offenders. Foreign property investors will pay a fee, to fund FIRB’s investigation and enforcement operations, and the Government would collect any capital gains made by foreign investors who illegally purchased established residential properties. Finally, penalties for breaches of the rules will be linked to the value of the property.

Liberal chair, Kelly O’Dwyer said:

“The Committee has undertaken a thorough review of the foreign investment framework as it applies to residential real estate. We have found that the framework itself is appropriate and strikes the right balance in terms of encouraging beneficial foreign investment in the housing market, however its application is severely lacking.”

“I regard the current internal processes at the Treasury and FIRB as a systems failure. Most concerning is that sanctions seem to be virtually non-existent. There have been no prosecutions since 2006 and no divestment orders since 2007. Suggestions by officials, that this is due to complete compliance with the rules is simply not credible. The data on foreign purchases of Australian houses and apartments is inadequate, making policy evaluations very difficult”…

“Australians must have confidence that the rules, including those that apply to existing homes, are being enforced. Our inquiry revealed, that as it stands today, they could not have that confidence.”

“This report makes 12 common sense recommendations to Government to enable proper enforcement of the existing framework for foreign investment in Australian housing; provide extra resources to do so; and accurately measure the impact of foreign investment by collecting accurate and timely data. These practical measures are critical in order to ensure that foreign investment in Australian housing continues to serve our national interest for future decades.”

This is a good step in increasing transparency in this important area.

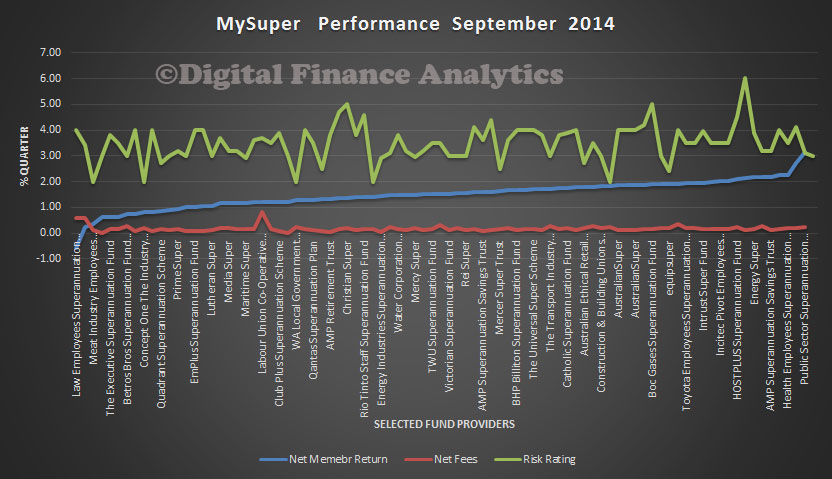

Quarterly MySuper Performance For September

APRA just released their statistics for the September 2014 quarter on the MySyper products which were part of the suite of superannuation reforms. The data must be treated with care, as some fees are not charged every quarter, but it does give a cross industry member view of performance returns. What is interesting is the apparent disconnect between the relative fees taken, risk profile, and returns. The interim Quarterly MySuper Statistics report contains data for all MySuper products. The report contains information on the product profile; product dashboard information reported to APRA on return target, investment risk and fees and costs; asset allocation targets and ranges; and net investment return and net return for each MySuper product, or where relevant, for the lifecycle stages underlying a MySuper product with a lifecycle investment strategy.

We have been looking at the MySuper products with single investment strategy data, and pulled out three measures, relative return to members in the quarters, relative fees paid, and relative risk profile. As there are more than 80 funds, we have not included all in the table labels in the chart below. APRA defines a Representative member as a member who is fully invested in the given investment option, who does not incur any activity fees during a year and who has an account balance of $50,000 throughout that year. Excludes: investment gains/losses on the $50,000 balance. The risk rating is based on the level of investment risk which represents the estimated number of years in each 20 years that the RSE licensee estimates that negative net investment returns will be incurred.

It would be possible, for the same level of fees to get a return of well over 2%, or below 1%. The relative risk does not correlate to returns at all. Fees are not correlated with performance. This provides an important window on the superannuation industry, but the data needs to be presented in ways which are clearer for people to interpret. Hopefully it will help to lift understanding amongst investors, and more proactively consider the performance of superannuation.

It would be possible, for the same level of fees to get a return of well over 2%, or below 1%. The relative risk does not correlate to returns at all. Fees are not correlated with performance. This provides an important window on the superannuation industry, but the data needs to be presented in ways which are clearer for people to interpret. Hopefully it will help to lift understanding amongst investors, and more proactively consider the performance of superannuation.

Finally, total assets in MySuper products was $378.1 billion at the end of the September 2014 quarter. Over the 12 months to September 2014 this represents a 128.2 per cent increase.