The Bank of England today published, in a special release, the minutes of Court and related meetings from the crisis period of 2007-09, in appropriately redacted form. This follows the Bank’s 11 December 2014 announcement of a series of proposals to enhance the transparency and accountability of the Bank. As part of this announcement, the Governor committed to publishing the 2007-2009 Court minutes, as requested by the Treasury Committee.

In the period covered by these minutes the Bank was operating within the statutory framework established in 1998. Court was much larger than the present Court, a number of members had standing conflicts of interest, and there was no provision for a non-executive chairman (to compensate for that, the Governor established the practice of having all Court business discussed first in the non-executive directors’ committee). At the time, the Bank had no powers to take actions to manage macro-prudential risks. It was not responsible for banking supervision and there was no bank resolution authority. The roles, in a crisis, of the Bank, the Treasury and the FSA were ill-defined. These deficiencies were rapidly identified during the period covered by the minutes, and were addressed both by the 2009 Banking Act and subsequently by the 2012 Financial Services Act, which radically changed both the role of the Bank and the structure of its governance.

Governor, Mark Carney said:

“The financial crisis was a turning point in the Bank’s history. The minutes provide further insight into the Bank’s actions during this exceptional period – the policies implemented to mitigate the crisis, the lessons that were learned, and how the Bank changed as a result.

The Bank is committed to increased openness and transparency and these minutes, in combination with the other recent reviews, provide a complete record of the Bank’s activities during the crisis.”

Author: Martin North

UK PRA Published its New “PRA Regulatory Digest”

Continuing their efforts to strengthen the effectiveness of their effective communications, the UK regulatory authorities have created a monthly digest of relevant releases and news. They say that

“this digest is for people working in the UK financial services industry and highlights key regulatory news and publications delivered for the month. Readers are encouraged to continue to visit the Bank of England website throughout the month, subscribe to alerts and visit the calendar for upcoming news and publications.”

We think the Australian Regulatory authorities should learn from this, as at the movement we have separate and disconnected release streams from RBA, APRA and ASIC. The UK effort shows the power of bringing material together into a more digestible form.

We think this should be coordinated by the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR). This body is the conductor of the regulatory orchestra, and has only had an independent website since 2013. It is the coordinating body for Australia’s main financial regulatory agencies. We discussed the role of CFR recently.

Latest Banking Statistics

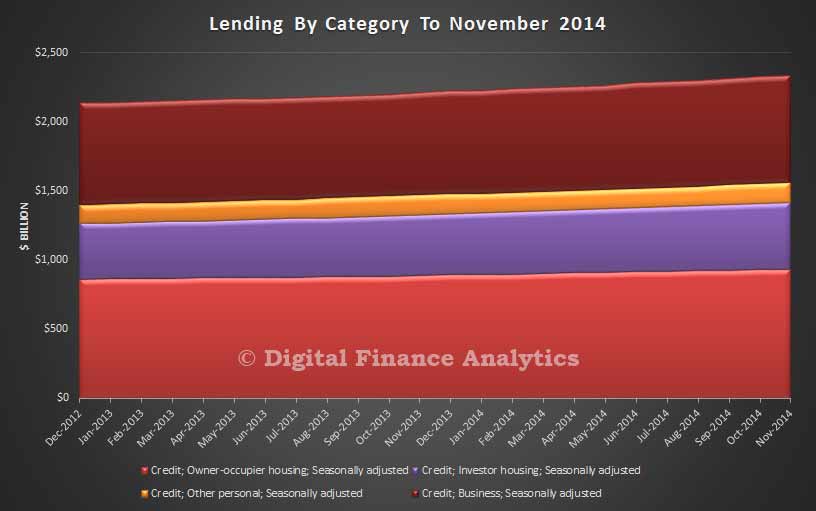

Last week saw the release of the November data from both the RBA and APRA. Looking at the overall summary data first, total credit grew by 5.9% in the year to November 2014. Housing lending grew at 7.1%, business lending at 4.6%, and personal credit by 1.1%.

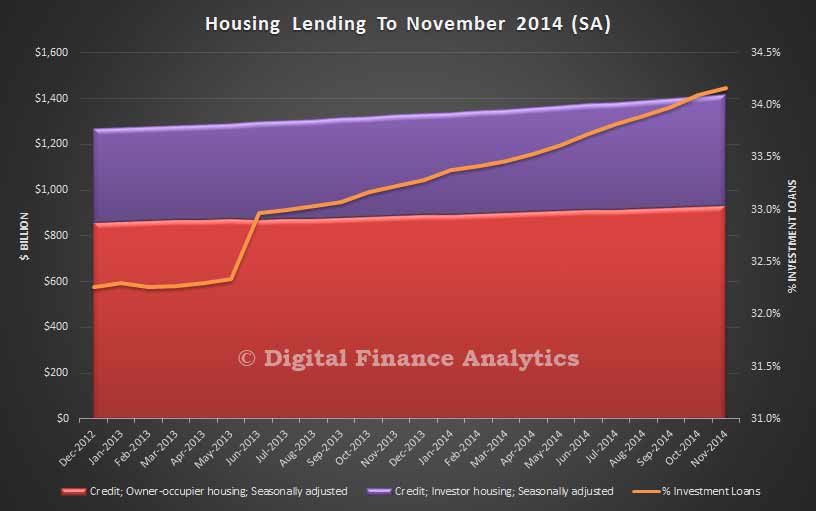

Looking at home lending, in seasonally adjusted terms, total loans on book rose to $1.42 trillion, with owner occupied loans at $932 billion, and investment loans at $483 billion, which equals 34.2%, a record.

Looking at home lending, in seasonally adjusted terms, total loans on book rose to $1.42 trillion, with owner occupied loans at $932 billion, and investment loans at $483 billion, which equals 34.2%, a record.

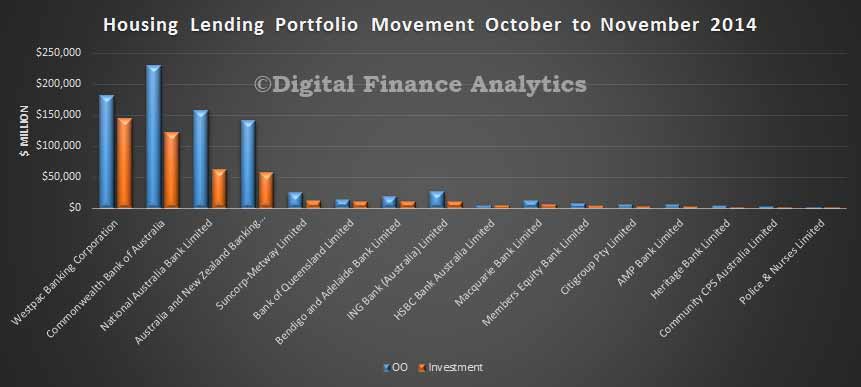

From the APRA data, loans by ADI’s were $1.31 trillion, with 34.82% investment loans, which grew at 0.84% in the month. Looking at relative shares, CBA continues to hold the largest owner occupied portfolio, whilst WBC holds the largest investment portfolio.

From the APRA data, loans by ADI’s were $1.31 trillion, with 34.82% investment loans, which grew at 0.84% in the month. Looking at relative shares, CBA continues to hold the largest owner occupied portfolio, whilst WBC holds the largest investment portfolio.

Looking at relative movement, WBC increased their investment portfolio the most in dollar terms. CBA lifted their owner occupied portfolio the most.

Looking at relative movement, WBC increased their investment portfolio the most in dollar terms. CBA lifted their owner occupied portfolio the most.

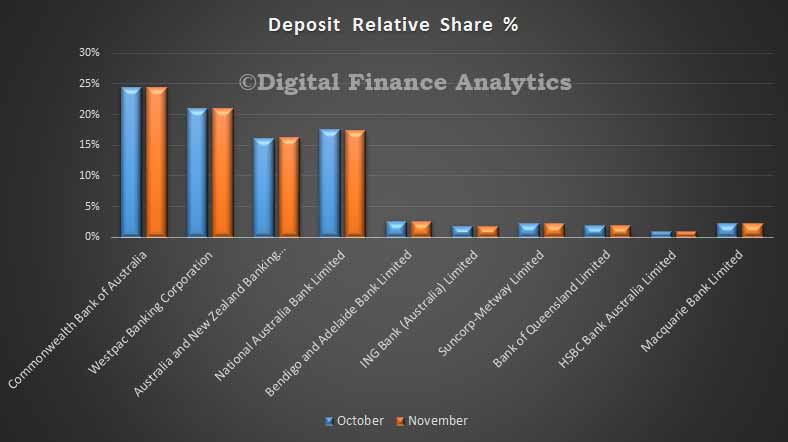

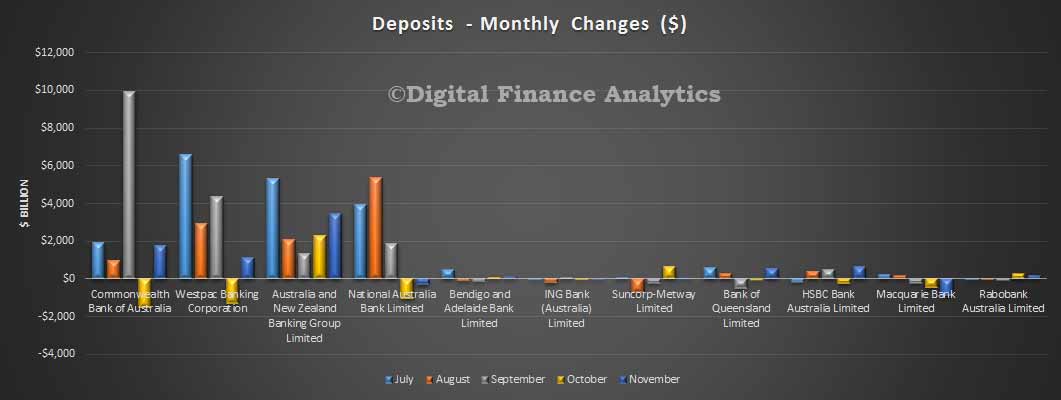

Turning to deposits, they rose 0.39% in the month, to 1.78 trillion.

Turning to deposits, they rose 0.39% in the month, to 1.78 trillion.

There was little change in relative market share, though we noted a small drop at nab, which relates to their cutting deposit rates from their previous market leading position.

There was little change in relative market share, though we noted a small drop at nab, which relates to their cutting deposit rates from their previous market leading position.

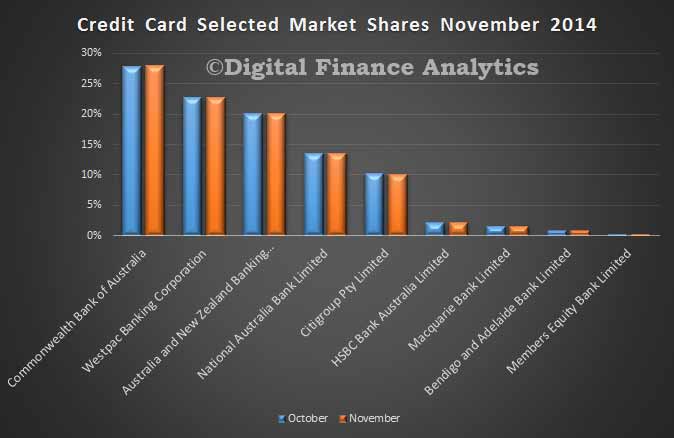

Finally, looking at the cards portfolios, the value of the market portfolio rose by $627 billion, to $41,052 billion. There were only minor portfolio movements between the main players.

Finally, looking at the cards portfolios, the value of the market portfolio rose by $627 billion, to $41,052 billion. There were only minor portfolio movements between the main players.

UK’s Financial System Not “Entirely Safe”

The UK’s financial system is not “entirely safe” according to former Bank of England governor Lord Mervyn King, speaking on BBC Radio 4’s Today programme. He questioned the banking system’s ability to withstand another crisis and argued the core problems that led to the meltdown have not yet been dealt with.

“I don’t think we’re yet at the point where we can be confident that the banking system would be entirely safe. I don’t think we’ve really yet got to the heart of what went wrong.”

The warning comes despite banks and other financial institutions being forced to hold more capital to prevent the risk of failure in the event of another downturn.

King, went on to say that imbalances between global economies have not yet been resolved. He added keeping base rate at the low of 0.5 per cent cannot go on .

“The idea that we can go on indefinitely with very low interest rates doesn’t make much sense.” However raising interest rates now “would probably lead to another downturn”.

He was at the helm of the Bank of England during the GFC.

His comments mirror some of the concerns highlighted in the recent Murray report.

Household Savings Intentions in 2015

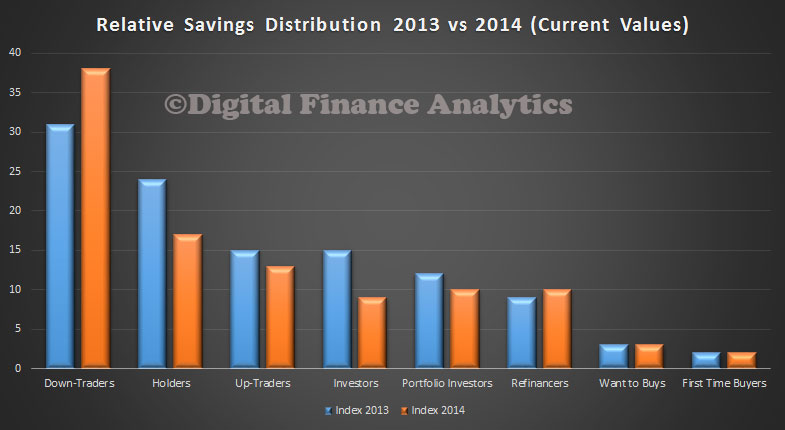

We have updated our savings intentions data, using results from our latest household surveys. Today we outline the main findings from the research. Using the DFA property segmentation, we can compare the relative value of savings across the segments, and compare this distribution with last year. In addition, we expect savings rates to be cut further next year.

We see that Down-Traders hold the largest relative share of savings, up from 32% last year to 38% this year. All other segments are at the same relative values as last year, or at lower levels. This highlights that people looking to sell and move to smaller properties are hold the most significant savings.

We see that Down-Traders hold the largest relative share of savings, up from 32% last year to 38% this year. All other segments are at the same relative values as last year, or at lower levels. This highlights that people looking to sell and move to smaller properties are hold the most significant savings.

In this analysis, savings includes balances in current accounts, call and term deposit accounts, and other liquid savings vehicles, but excludes property, shares are superannuation.

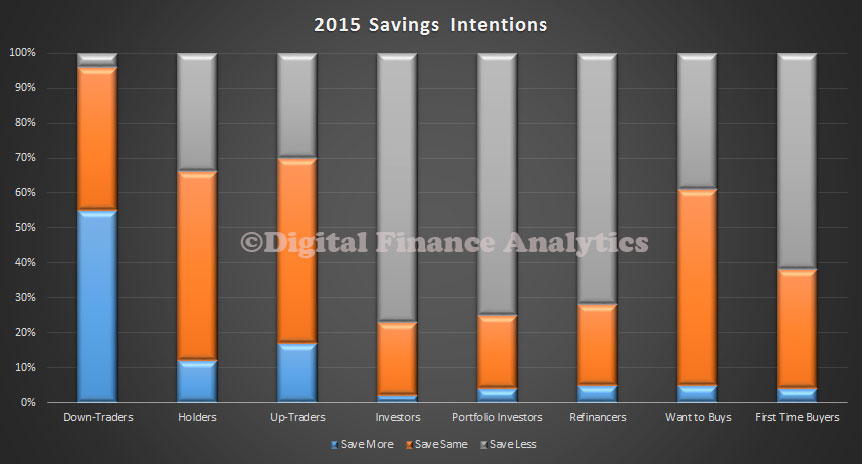

Looking at savings intentions, we see that Down-Traders are expecting to save more next year (55%), and only 5% are expecting to be savings smaller amounts. Investors, Portfolio Investors and Refinancers are more likely to be saving less next year. Want to Buys and First Time Buyers are also quite likely to do the same next year.

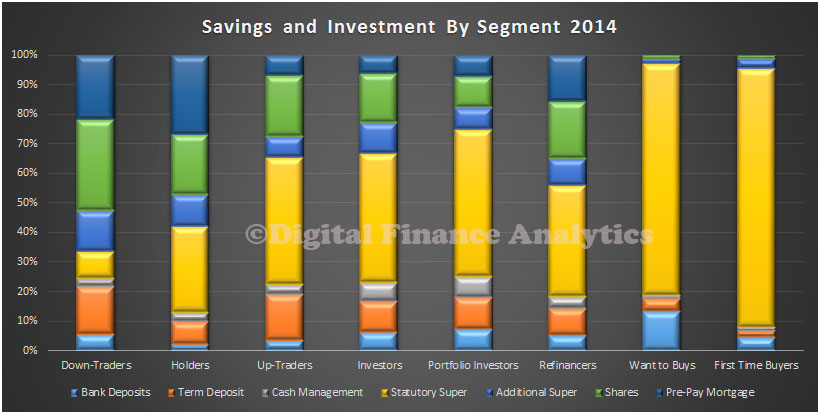

We can also look at the relative distribution of saving and investment vehicles by type. For some, the main vehicle is statutory superannuation, whereas for some other groups, bank deposits and cash management accounts are more significant. We also highlight the importance of pre-paying the mortgage for some segments.

We can also look at the relative distribution of saving and investment vehicles by type. For some, the main vehicle is statutory superannuation, whereas for some other groups, bank deposits and cash management accounts are more significant. We also highlight the importance of pre-paying the mortgage for some segments.

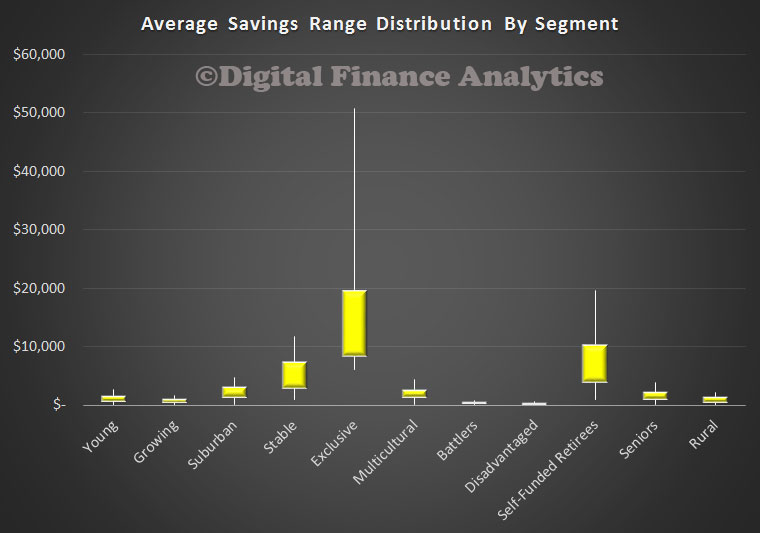

At this point, we introduce our master household segments, and show the relative savings distribution across these segments. By far the largest balances are held by the Exclusive segment, followed by Self-Funded Retirees. The chart shows the relative distribution, with the yellow box showing the 50% distribution bounding.

At this point, we introduce our master household segments, and show the relative savings distribution across these segments. By far the largest balances are held by the Exclusive segment, followed by Self-Funded Retirees. The chart shows the relative distribution, with the yellow box showing the 50% distribution bounding.

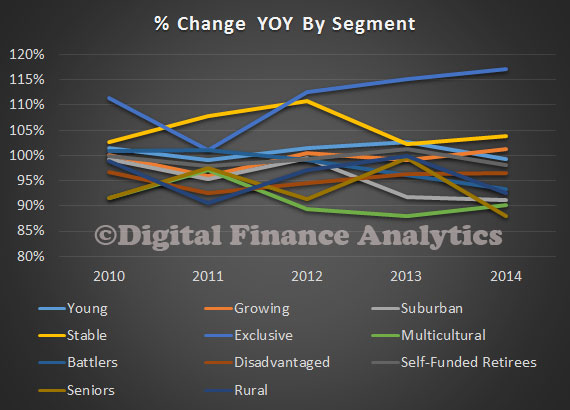

We also see some trends by looking across segments over time. Exclusive and Stables household segments are seeing balances increasing, whereas Seniors and Self-Funded Retirees are seeing balances falling. In our analysis we saw that these older groups are especially feeling the impact of lower savings rates.

We also see some trends by looking across segments over time. Exclusive and Stables household segments are seeing balances increasing, whereas Seniors and Self-Funded Retirees are seeing balances falling. In our analysis we saw that these older groups are especially feeling the impact of lower savings rates.

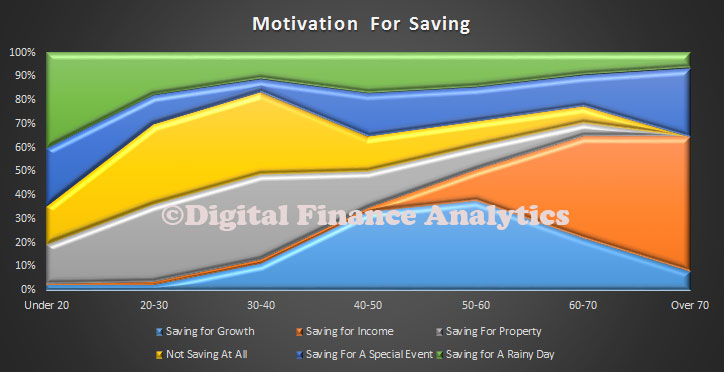

Another way to look at the savings scene, is to examine the motivations for savings. The chart below shows the relative distribution by age bands. Significantly, many households in the 20-30 and 30-40 age ranges are not saving at all. Older households are more likely to be saving for growth, whereas the oldest households are most likely to be saving for income.

Another way to look at the savings scene, is to examine the motivations for savings. The chart below shows the relative distribution by age bands. Significantly, many households in the 20-30 and 30-40 age ranges are not saving at all. Older households are more likely to be saving for growth, whereas the oldest households are most likely to be saving for income.

65% of younger households are most likely saving for a specific event (e.g. holiday, car, wedding) or for a rainy day. We see that saving for property purchase peaks in the 30-40 years age group.

65% of younger households are most likely saving for a specific event (e.g. holiday, car, wedding) or for a rainy day. We see that saving for property purchase peaks in the 30-40 years age group.

We believe that households will continue to be cautious in 2015, and that will savings rates continuing to fall, we will see many saving more, not less. The RBA remains keen to encourage households to spend more, but the research shows that saving remains important for those with the largest balances, and many are stress by costs of living rising, savings rates falling, and therefore are expecting to save less.

This is the last post for 2014. Thanks to all those who follow, read and comment on the DFA Blog. We will be back early in 2015, with fresh insight and updated surveys. Meantime happy holidays.

The Capital Conundrum II

A series of separate but connected events will see capital requirements of banks continue to steadily increase from 2015 onwards. You can read about the capital issues in the earlier post. This is consistent with the outcomes from the G20. The international environment is driving capital requirements higher (on the back of the northern hemisphere government bailouts post the GFC). Locally the regulators are also making moves, and the recommendations from the Murray Financial Systems Inquiry (FSI) are also in play. Overall, some of the most significant elements are:

- Globally Significantly Banks (GSIBs) likely to need to hold more capital, and this will likely flow down to other banks also.

- Latest BIS recommendations on floors and ratios

- APRA changing the liquidity coverage ratio

- FIS on capital ratios

- FIS on advanced IRB banks

There are other steps in the works also. The net effect is that capital requirements will be lifting in 2015, irrespective of the FSI (and the capital changes recommended do not need parliamentary approvals).

Here is DFA’s view of how these outcomes will translate in the Australian context

- Banks need to raise $20-40 bn over next couple of years, – that is doable – and they will access the now functioning global markets. It will be ratings positive.

- Smaller banks will be helped by the FSI changes to advanced IRB, if they translate, but will still be at a funding disadvantage

- Deposit rates will be cut, they have been falling already despite RBA rate being static, this has not received enough commentary, there are millions of households reliant on income from deposits

- Mortgage rates will lift a little, and discounting will be even more selective – Murray’s estimates on the costs are about right.

- Lending rates for small business will rise further

- Competition won’t be that impacted, and the four big banks will remain super profitable

- We will still have four banks too big to fail, and the tax payer would have to bail them out in the event of a failure (highly unlikely but not impossible given the slowing economic environment here, and uncertainly overseas). The implicit government guarantee is the real issue.

Capital floors: The Design of a Framework Based on Standardised Approaches

The BIS also released a consultative paper which outlines the Basel Committee’s proposals to design a capital floor based on standardised, non-internal modelled approaches. The proposed floor would replace the existing transitional capital floor based on the Basel I framework. The floor will be based on revised standardised approaches for credit, market and operational risk, which are currently under consultation.

The floor is meant to mitigate model risk and measurement error stemming from internally-modelled approaches. It would enhance the comparability of capital outcomes across banks, and also ensure that the level of capital across the banking system does not fall below a certain level.

As noted in the Committee’s November 2014 report to the G20 Leaders, the Committee is taking steps to reduce variation in capital ratios between banks. The proposed capital floor is part of a range of policy and supervisory measures that aim to enhance the reliability and comparability of risk-weighted capital ratios. The Committee will consider the calibration of the floor alongside its work on finalising the revised standardised approaches.

Revisions to the Standardised Approach for Credit Risk

BIS has just released a proposal to strengthen the existing regulatory capital standards for discussion. This is one of a number of initiatives which are all driving capital requirements higher.

The proposed Revisions to the Standardised Approach for credit risk seek to strengthen the existing regulatory capital standard in several ways. These include:

- reduced reliance on external credit ratings;

- enhanced granularity and risk sensitivity;

- updated risk weight calibrations, which for purposes of this consultation are indicative risk weights and will be further informed by the results of a quantitative impact study;

- more comparability with the internal ratings-based (IRB) approach with respect to the definition and treatment of similar exposures; and

- better clarity on the application of the standards.

The Committee is considering replacing references to external ratings, as used in the current standardised approach, with a limited number of risk drivers. These alternative risk drivers vary based on the particular type of exposure and have been selected on the basis that they are simple, intuitive, readily available and capable of explaining risk across jurisdictions.

Given the challenges associated with identifying risk drivers that can be applied globally but which also reflect the local nature of some exposures – such as retail credit and mortgages – the Committee recognises that the proposals are still at an early stage of development. Thus, the Committee seeks respondents’ comments and analysis with a view to enhancing the proposals set out in this consultative document.

The key aspects of the proposals are:

- Bank exposures: would no longer be risk-weighted by reference to the bank’s external credit rating or that of its sovereign of incorporation, but would instead be based on two risk drivers: the bank’s capital adequacy and its asset quality.

- Corporate exposures: would no longer be risk-weighted by reference to the borrowing firm’s external credit rating, but would instead be based on the firm’s revenue and leverage.

- Further, risk sensitivity and comparability with the IRB approach would be increased by introducing a specific treatment for specialised lending.

- Retail category: would be enhanced by tightening the criteria to qualify for a preferential risk weight, and by introducing an alternative treatment for exposures that do not meet the criteria.

- Residential real estate: would no longer receive a 35% risk weight. Instead, risk weights would be based on two commonly used loan underwriting ratios: the amount of the loan relative to the value of the real estate securing the loan (ie the loan-to-value ratio) and the borrower’s indebtedness (ie a debt-service coverage ratio).

- Commercial real estate: two options are currently under consideration: (a) treating the exposures as unsecured with national discretion for a preferential risk weight under certain conditions; or (b) determining the risk weight based on the loan-to-value ratio.

- Credit risk mitigation: the framework would be amended by reducing the number of approaches, recalibrating supervisory haircuts and updating the corporate guarantor eligibility criteria.

ASIC Provides Relief for 31-day Notice Term Deposits

ASIC today released a class order to facilitate term deposits that are only breakable on 31 days’ notice.

The Class Order [CO 14/1262] gives relief for 18 months to enable 31-day notice term deposits of up to five years to be given concessional regulatory treatment as basic deposit products under the Corporations Act (the Act). This is intended to give Government the opportunity to consider law reform.

As part of the Basel III reforms, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) will implement the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) requirement from 1 January 2015, as set out in Prudential Standard APS 210 Liquidity (APS 210).

Term deposits that require 31 days’ notice for early withdrawal will receive favourable liquidity treatment under APS 210.

The new class order will provide industry with certainty that these sorts of term deposits will be treated as basic deposit products, subject to meeting the relief conditions.

The class order formalises ASIC’s previous conditional no-action position on 31-day notice term deposits. The relief conditions are about ensuring consumers can make confident and informed decisions when investing in the new type of term deposit.

They also help consumers understand the new requirement to give 31 days’ notice to ‘break’ their term deposit and ensure this is considered when the term deposit rolls-over.

ASIC will continue to work with industry to help ADIs meet the relief conditions, including carryover of arrangements from the previous no-action position to the class order, while ensuring consumer protection.

Background

The definition of basic deposit product in section 761A of the Act does not specify the period of notice an ADI may require a depositor to give in order to make an early withdrawal from a term deposit of up to two years.

It is therefore unclear what notice period for withdrawal could be imposed that is consistent with the characterisation of a term deposit of up to two years as basic deposit product. ASIC’s view is that a notice period as long as 31 days for early withdrawal is unlikely to meet the definition of basic deposit product.

Section 761A of the Act provides that term deposits of between two and five years must allow an early withdrawal without prior notice in order to meet the basic deposit product definition (except for the special provision for mutual ADIs contained in reg 7.1.03A of the Corporations Regulations 2001).

Long-Term Unemployment Will Impact Wage Growth

In economic circles, the relationship between wage growth and unemployment is an important factor. Many will focus on the relationship between short-term unemployment and wage growth, but a paper released by the Bank of England highlights that long-term unemployment is also an important factor in the equation. Given the fact that wage growth is slowing in Australia, and long-term unemployment is rising, these findings are important.

The relationship between wage growth and unemployment is a key trade-off concerning monetary policy makers, as labour costs form a critical part of the inflationary transmission mechanism. One important question is how the composition of the unemployment pool, and specifically the share of long-term unemployment, affects that tradeoff. Detachment from the labour force is likely to increase with unemployment duration, so that the long-term unemployed search less actively for jobs and therefore exert less downward pressure on wages. If so, short-term unemployment may pull down on wage inflation more than long-term unemployment does. In this situation, policymakers might anticipate a period of high wage growth if short-term unemployment starts to fall to low levels even if the long-term unemployment rate remains elevated.

But there may be complications arising from the integral dynamics of unemployment. In this paper it emerges that the estimated disinflationary effects of long-term unemployment hinge on whether or not wage growth becomes less sensitive to unemployment as the latter rises – a form of non-linearity. One reason why the negative relationship between wages and unemployment might become flatter at high levels of unemployment is that workers may tend to resist cuts in their nominal wages. When unemployment is low, wage growth tends to be high as firms compete for a scarce pool of resources. But due to worker resistance to wage cuts the reverse might not hold to the same extent, with a relatively large increase in unemployment needed to reduce wage growth during a recession.

Why does this non-linearity matter for the measured effect of long-term unemployment on wage growth? It is because long-term unemployment inevitably lags behind movements in short-term unemployment as it takes time for the new unemployed to move into the long-term category. So high levels of long-term unemployed are only associated with lengthy periods of high unemployment. A flattening off of the relationship between wages and unemployment at high levels of unemployment would then imply that long-term unemployment does little to reduce wage inflation further. The apparently different effects of short and long-term unemployment on wage inflation could therefore be merely as a result of timing rather than labour market detachment among the long-term unemployed.

By modifying statistical models of labour market dynamics to incorporate this insight, this paper finds that there appears to be much less difference between the short and long-term unemployed in terms of their marginal influence on wage behaviour than is suggested by the recent literature. When the non-linearity described above is not taken into account, estimation results corroborate the finding already established in the literature that it is predominantly the short-term unemployed that matter for wage inflation. Long-term unemployment in this specification tends to have no statistically significant effect on wage inflation. When the non-linearity is taken into account, long-term unemployment has a much larger effect on wage inflation. For some of the specifications considered, the data fail to reject the hypothesis that short and long-term unemployment rates have equal effects on inflation. In some instances, the models even suggest that long-term unemployment creates more of a drag on wage growth than short-term unemployment does, all else equal. Statistical uncertainty makes it difficult to draw a very precise conclusion, but the results in this paper caution against excluding long-term unemployment from estimates of aggregate labour market slack as is suggested by much of the recent literature. Both the short-term unemployment rate and the long-term unemployment rate are likely to contain useful information for judging the degree of wage pressure in the economy.