The Federal Reserve Board’s latest survey of the financial and economic conditions of American households released Wednesday finds that individuals’ overall perceptions of financial well-being improved modestly between 2013 and 2014 but their optimism about future financial prospects increased significantly.

The 2014 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking, provides new insight into Americans’ economic security, housing and living arrangements, banking and credit access, education and student loan debt, savings behavior, and retirement preparedness. Sixty-five percent of adult respondents consider their families to be either “doing okay” or “living comfortably” financially–an increase of 3 percentage points from the 2013 survey.

Looking forward, households are increasingly optimistic. Twenty-nine percent of survey respondents say they expect their income to be higher in the year following the survey, compared to 21 percent of 2013 respondents.

The survey results reveal a lack of economic preparedness among many adults. Only 53 percent of respondents indicate that they could cover a hypothetical emergency expense costing $400 without selling something or borrowing money. Thirty-one percent of respondents report going without some form of medical care in the past year because they could not afford it.

The outlook for the housing market among surveyed homeowners remained generally positive, as 43 percent believe that their house increased in value over the past year and 39 percent expect home values in their neighborhood to rise in the coming year. Many renters also express an interest in buying but report financial barriers to homeownership, with half of all renters listing an inability to afford a down payment as a reason why they rent rather than own and 31 percent citing an inability to qualify for a mortgage as a reason for renting.

Twenty-three percent of the adult population has some form of education debt, according to the survey. However, this debt is not exclusively student loans. Fourteen percent of those with education debt say that some of that debt is on credit cards. Individuals who did not complete an associate or bachelor’s degree, first generation students, blacks and Hispanics, and those who attended for-profit institutions, are all disproportionately likely to be behind on repaying their student loan debt.

Recognizing the importance of degree completion to many outcomes, the survey explores why some individuals leave college without a degree. Family responsibilities is the most common reason, and was cited by 38 percent of all respondents who dropped out and by just less than half of women younger than 45.

The survey results also suggest that many individuals are not adequately prepared for retirement. Thirty-one percent of non-retirees have no retirement savings or pension, including nearly a quarter of those older than 45. Even among individuals who are saving, fewer than half of adults with self-directed retirement savings are mostly or very confident in their ability to make the right investment decisions when managing their retirement savings.

Consistent with a lack of preparedness for retirement, 38 percent of non-retired respondents say that they either do not plan to retire or plan to keep working as long as possible. Among lower-income respondents, whose household income is less than $40,000 per year, 55 percent plan to keep working as long as possible or never plan to retire.

The survey was conducted on behalf of the Board in October and November 2014. More than 5,800 respondents completed the survey. The report summarizing the survey’s key findings may be found at: http://www.federalreserve.gov/communitydev/shed.htm

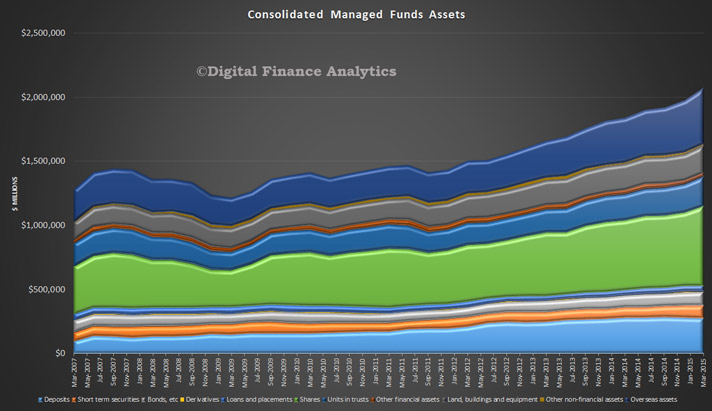

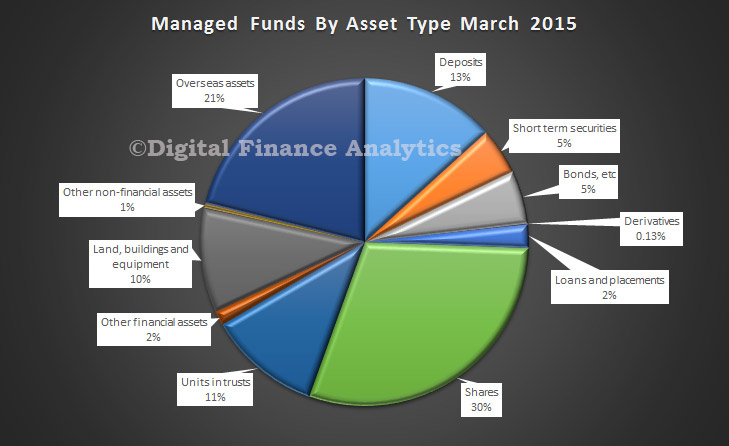

The asset types that increased were shares, $45.8b (8%); overseas assets, $34.2b (8%); units in trusts, $10.8b (5%); other financial assets, $3.4b (13%); short term securities, $3.3b (4%); bonds, etc., $2.9b (3%); land, buildings and equipment, $2.7b (1%); loans and placements, $0.9b (2%); and derivatives, $0.7b (34%). These were partially offset by decreases in deposits, $4.3b (2%); and other non-financial assets, $0.1b (1%). The chart below shows the unconsolidated mix at end March 2015.

The asset types that increased were shares, $45.8b (8%); overseas assets, $34.2b (8%); units in trusts, $10.8b (5%); other financial assets, $3.4b (13%); short term securities, $3.3b (4%); bonds, etc., $2.9b (3%); land, buildings and equipment, $2.7b (1%); loans and placements, $0.9b (2%); and derivatives, $0.7b (34%). These were partially offset by decreases in deposits, $4.3b (2%); and other non-financial assets, $0.1b (1%). The chart below shows the unconsolidated mix at end March 2015. At 31 March 2015, there were $536.7b of assets cross invested between managed funds institutions. At 31 March 2015, the unconsolidated assets of superannuation (pension) funds increased $106.2b (6%), life insurance corporations increased $14.3b (5%), public offer (retail) unit trusts increased $8.9b (3%), cash management trusts increased $1.4b (6%), friendly societies increased $0.2b (2%), and common funds increased $0.1b (1%).

At 31 March 2015, there were $536.7b of assets cross invested between managed funds institutions. At 31 March 2015, the unconsolidated assets of superannuation (pension) funds increased $106.2b (6%), life insurance corporations increased $14.3b (5%), public offer (retail) unit trusts increased $8.9b (3%), cash management trusts increased $1.4b (6%), friendly societies increased $0.2b (2%), and common funds increased $0.1b (1%).