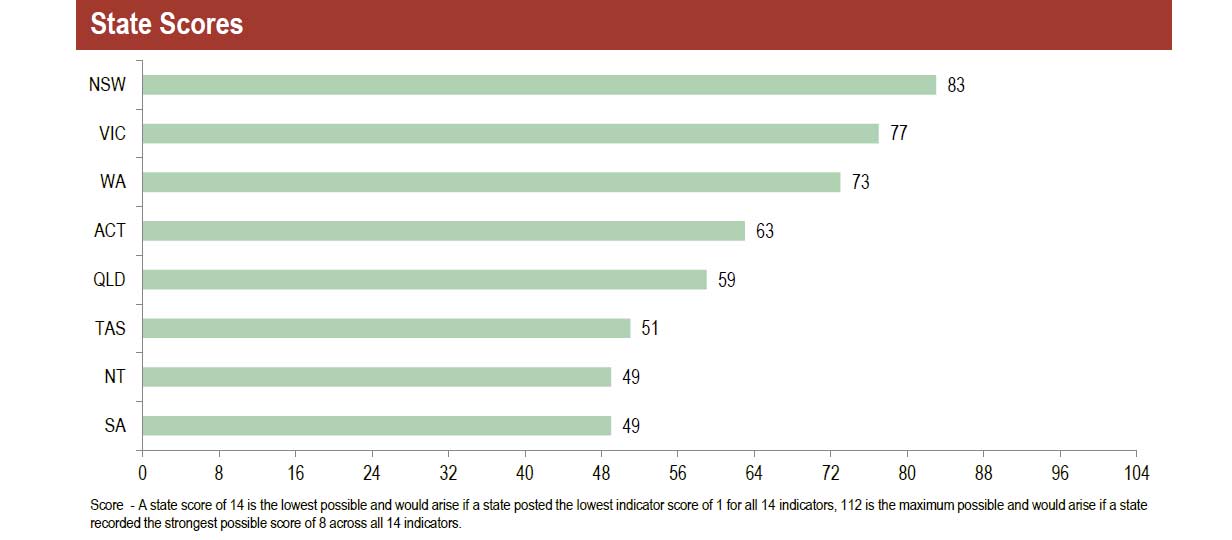

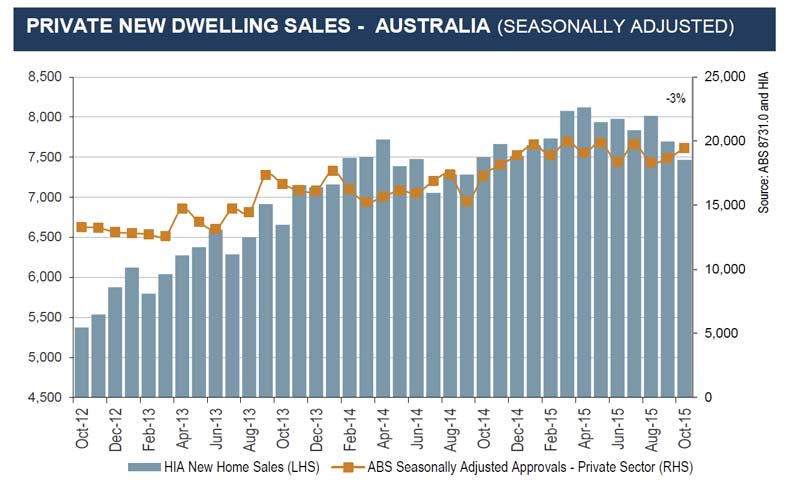

The latest edition of the HIA Housing Scorecard was released today. There are significant and important state variations in activity and outcomes and the scorecard nicely highlights some of the contracts. For example, first time buyers in NSW continue to languish, whilst WA has strong construction activity and NT housing finance fell. SA and NT registered the lowest scores.

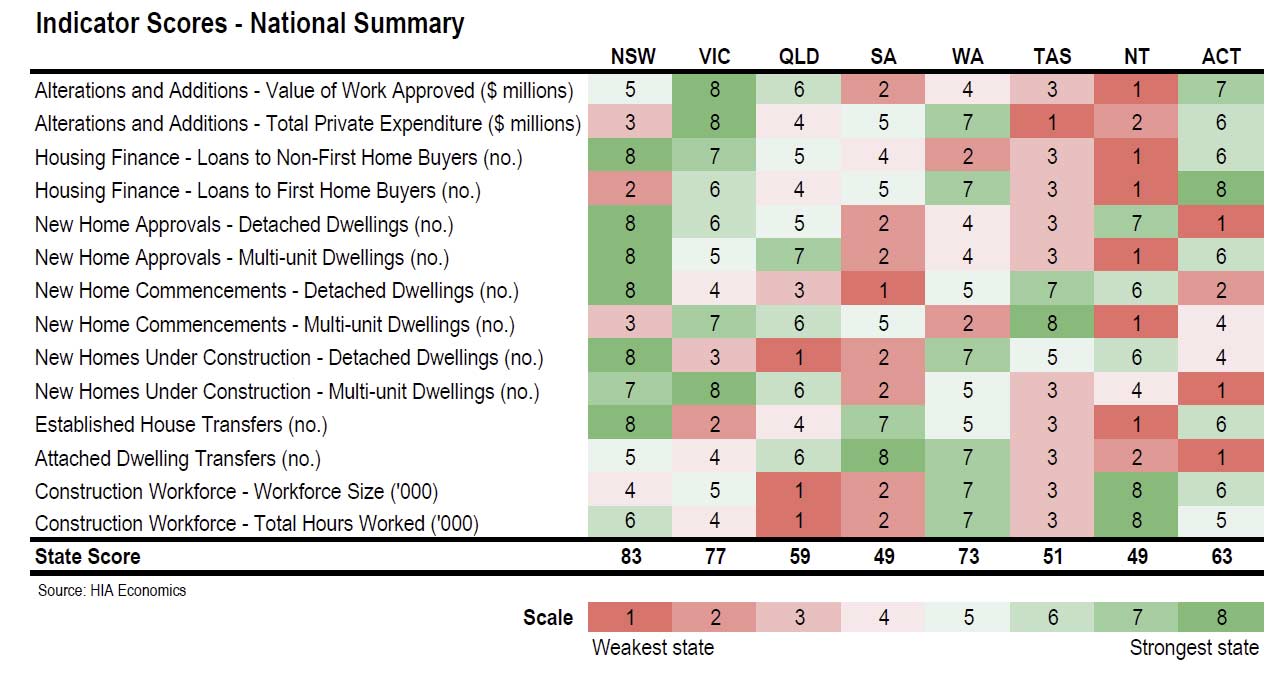

The Housing Scorecard provides a half yearly review of residential building conditions in each state and territory. Across a range of activity indicators, the most recent performance in each state is benchmarked against the state’s longer term average. This analysis is aggregated in a scoring system which provides a ranking that highlights the relative strength or weakness of residential building activity in each state and territory. The indicators include (using ABS data):

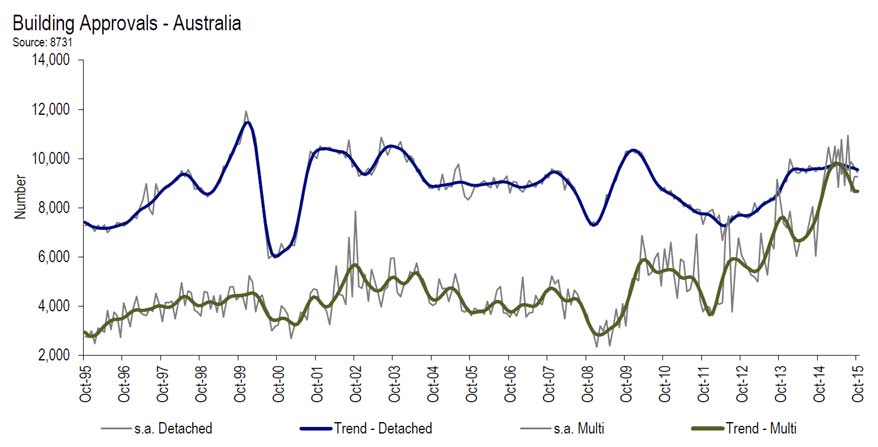

- Detached house building;

- Multi-unit dwelling building;

- Renovations;

- Construction labour force;

- Housing finance; and

- Turnover of established homes

This analysis is aggregated in a scoring system to generate a league table ranking the relative strength/weakness of residential building conditions in each jurisdiction. For each indicator, each state is assigned an indicator score where a state receives a score of eight if they are the strongest relative to their long term average and progressively lower scores assigned for the weaker states. A score of one is assigned to the state with the weakest level of activity relative to their long term average.

The indicator scores assigned for each state are summed together which becomes the state score. The state score provides the basis for the overall ranking of the states. The states are ranked in descending order based on the state score. The highest scoring state is ranked number one and each state is ranked in descending order with the state achieving the lowest score ranking eighth.

New South Wales continued to hold down top spot with a score of 83, taking out the top indicator score in six of the fourteen indicators.

NSW scored strongly in the key leading indicators of new home building activity, and those relating to the housing market more broadly. Relating to new home building, NSW scored most favourably in the indicators tracking detached house construction – taking top spot for approvals of detached houses, as well as

commencements and the number of dwellings currently under construction.

NSW also scored well in the indicators of multi-unit dwelling approvals, with activity in the September 2015

quarter more than double the decade average – and the multi-unit dwellings under construction category. Against the backdrop of such strong leading indicators of multiunit building activity, NSW’s ranking for multi-unit dwelling commencements appears out of step. However, this is consistent with the accumulation of dwellings that have been approved, but have not yet been commenced.

Typically home price growth provides the catalyst for a rise in renovations activity, however this is yet to fully

materialise in in the current cycle. NSW ranks fourth in terms of the value of work approved, and sixth in terms of the aggregate value of renovations investment.

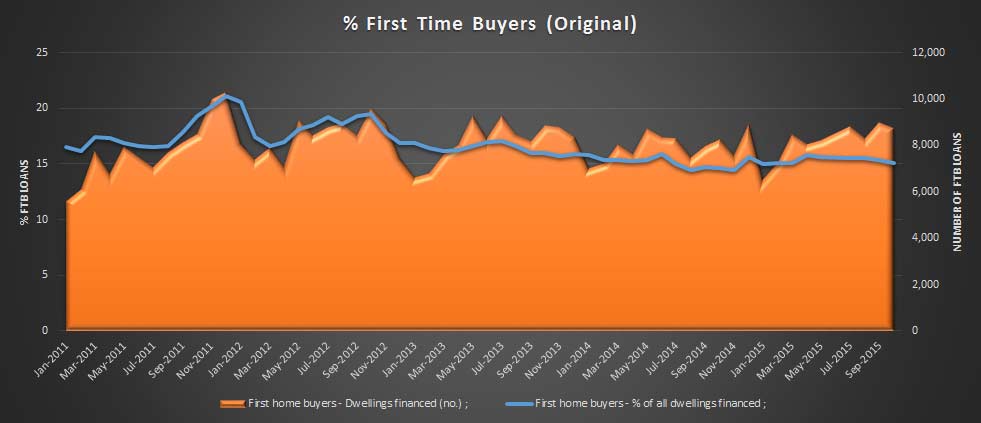

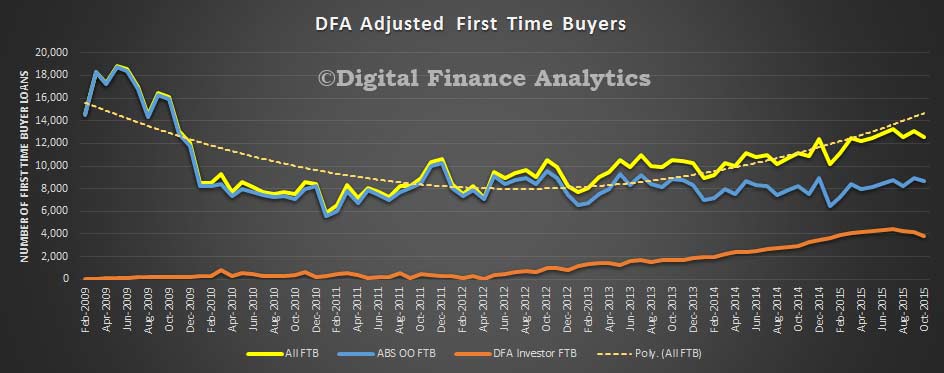

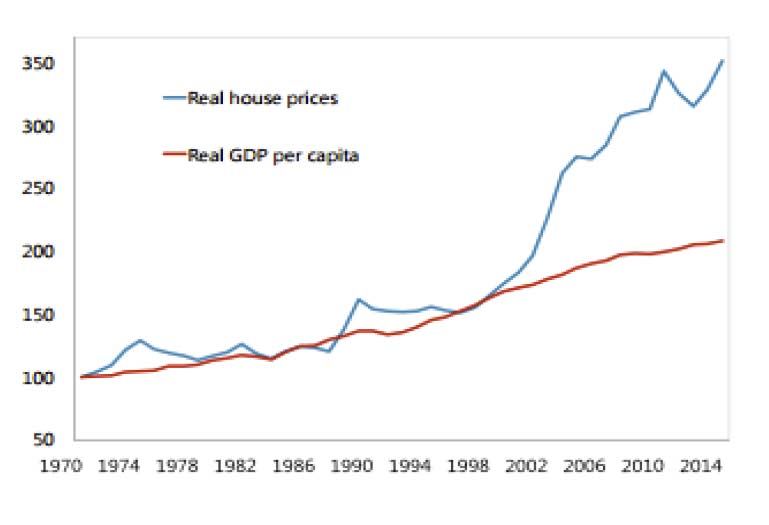

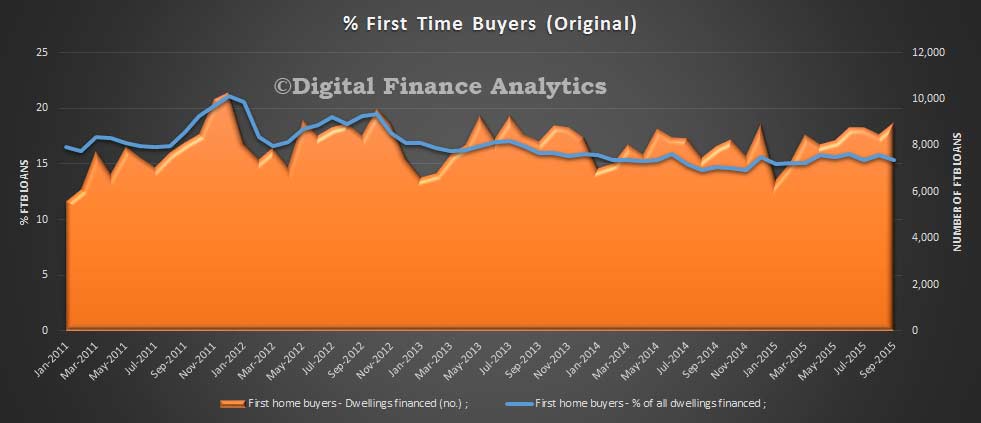

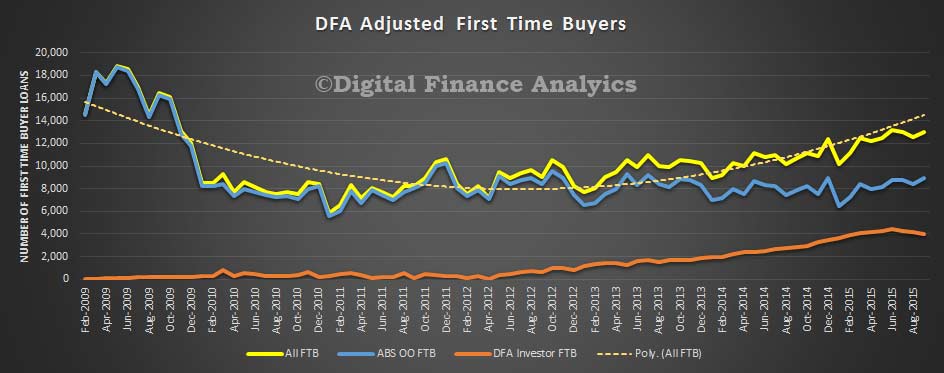

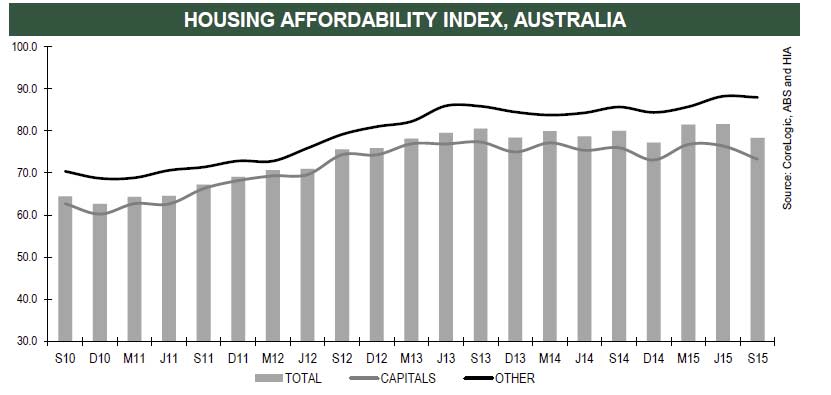

The weakest part of the NSW picture relates to first home buyers. This will come as little surprise given the extent to which the escalation in home prices in the state has outpaced household income growth over the last year or more. The number of loans to first home buyers in the September 2015 quarter was 21.7 per cent below the long term average, which ranks as the second weakest of the eight jurisdictions.

VIC

Whereas NSW is the king of new home building at the moment, Victoria is the king of home renovations. Once

again, the strong performance of the renovations market has underpinned Victoria’s high overall ranking.

In terms of private expenditure on home renovations, Victoria continues its run as the top ranked state to four consecutive quarters and has been the top ranked state on this indicator in eleven of the last thirteen quarters.

Victoria is the only jurisdiction in the nation to record a level of expenditure that was higher than its decade

average in the September 2015 quarter, and has been the only one to consistently do so over the last couple of

years. However, other states territories are now showing signs of improving so it will be a challenge for Victoria to hold on to the top ranking in the quarters ahead.

Victoria also continues to record strong performances for indicators tracking multi-unit dwelling construction.

The state ranks as the second strongest state in terms of the number of multi-unit dwellings commenced and the top ranked jurisdiction for multi-unit dwellings under construction. However, for the number of multi-unit

dwellings approved, which is a more forward looking indicator, the state has dropped to fourth in the rankings.

First home buyer lending activity in Victoria provides an interesting contrast to their neighbours to the north. While both Melbourne and Sydney have seen rapid home price growth push some first home buyer to the sidelines, the lending figures suggest the impact has been much smaller in Victoria. With the number of loans in the September 2015 quarter being only 5.4 per cent below the decade average, Victoria ranks as the third strongest market for first home buyers.

QLD

After the state score dropped to a lowly 22 back when Queensland was the lowest ranking jurisdiction for a spell during 2011, the state has made steady incremental improvements and now ranks fifth with a score of 59.

Furthermore, there is now daylight between QLD and the lower ranked states, and fourth placed the ACT is within striking distance.

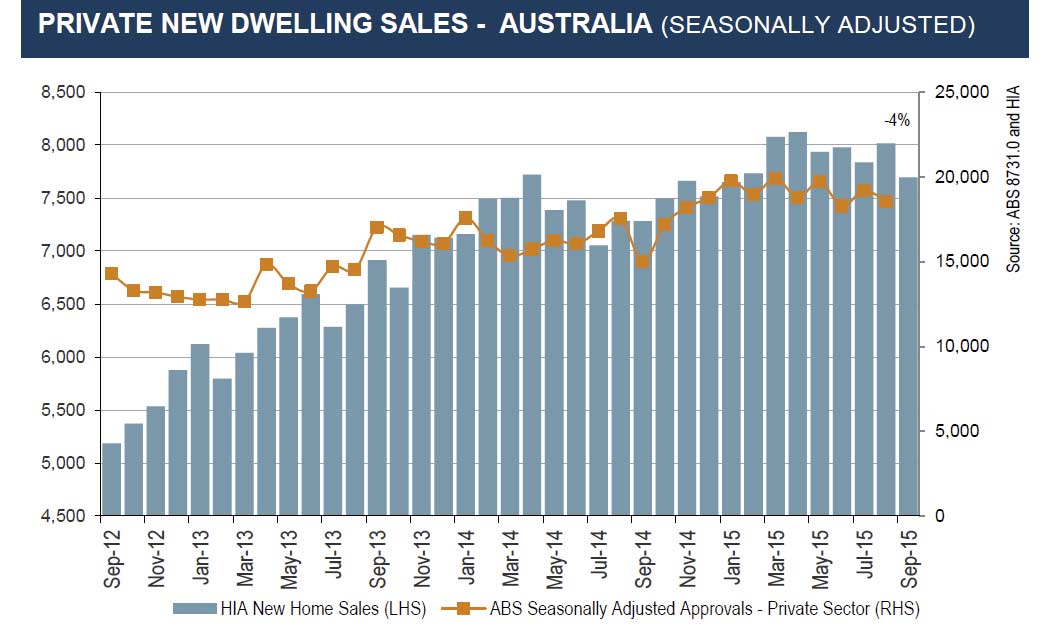

The indicators of multi-unit activity have been a source of strength for QLD. In terms of multi-unit approvals, with 6,130 approvals during the September 2015 quarter providing a level 88.4 per cent higher than the decade average, the state ranks second amongst the states and territories. In addition, the state’s rankings for multi-unit commencements and the number of multi-unit dwellings under construction both increased two places to rank third overall in each indicator.

One of the key weak points in QLD’s overall position is indicative of a broader economic challenge the state is

facing. In terms of the number of people employed in construction and the aggregate hours worked by the

construction workforce, the state ranks stone cold last. The number of workers employed in the construction

industry is 13.6 per cent down on the decade average, while the aggregate number of hours was down by 15.0

per cent.

It is important to note that these labour market indicators track the entire construction workforce (not just those in residential building) and this is being influenced by the conclusion of a number of major resource projects. A recovery in non-residential building and a continuation of the recovery in residential activity will be essential if the state is to see a much needed revival of its non-resource industries.

SA

While South Australia’s state score lifted by three points over the last six months, the state’s ranking held steady at number seven which makes it equal last (alongside the NT) in this edition of the HIA Housing Scorecard.

Consistent with the last edition of this report, the turnover of established dwellings was a strong point for SA. The state ranks as the second strongest for turnover of established houses (bettered only by NSW), while the

state ranks as the top ranked state for turnover of attached dwellings. While this is a positive sign for the

real estate industry, it hasn’t correlated with positive signs for residential building.

The state’s detached house segment is a weak point. In terms of detached house commencements, the number of new housing starts in the latest quarter (June 2015) was 24.5 per cent below the decade average – ranking it is the weakest jurisdiction nationally. In addition, the state ranked second weakest in terms of approvals for detached houses and for the number detached houses under construction.

Again, there were mixed readings for indicators of renovations activity. The value of large renovation jobs

approved in the September 2015 quarter was relatively weak and ranked as the second weakest jurisdiction

nationally. However, SA ranked fourth in terms of the total value of private investment in alterations and

additions.

WA

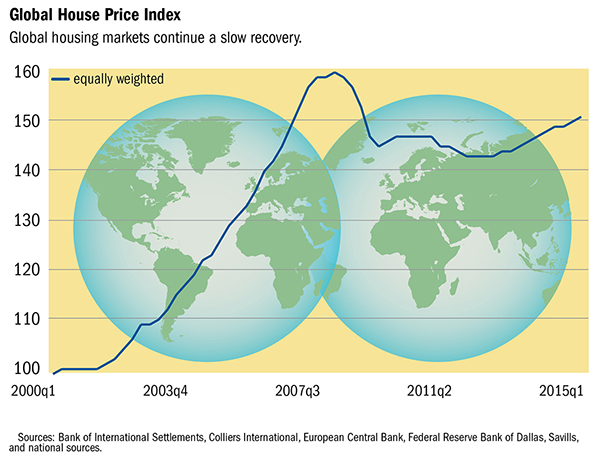

While Western Australia’s place on the national league table has slipped again, third place is still a good result,

indicating that overall conditions in the state’s housing sector remain healthy. Most elements of the sector are

still outperforming their respective decade averages. The details highlight that WA is still benefitting from what appears to be quite a ‘long tail’ to the state’s new home building boom.

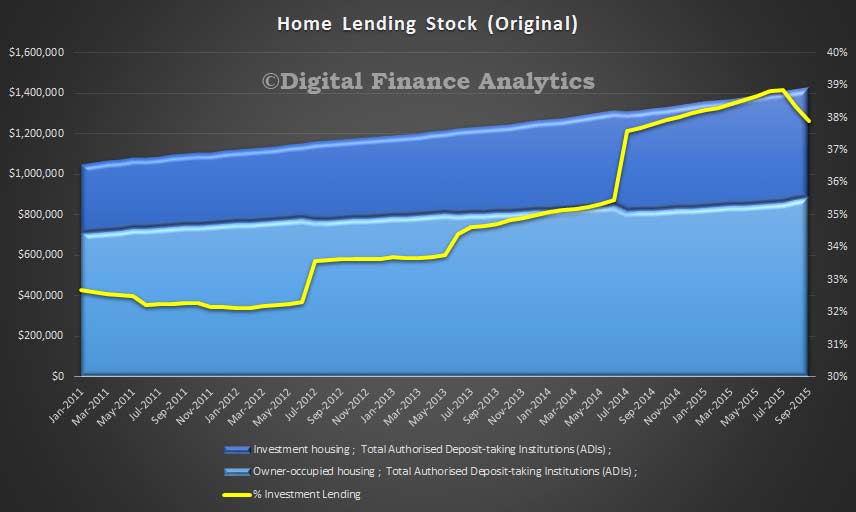

Of the 14 housing market indicators, WA achieved the second strongest score rankings in six: total expenditure of alterations and additions, lending to first home buyers; number of detached dwellings under construction; number of attached dwelling transfers; size of the construction work force, and; total hours worked by the construction workforce.

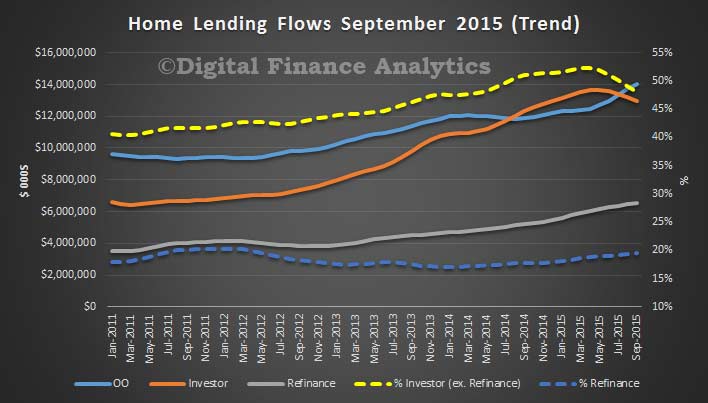

Where WA is starting to feel the effects of the emerging downturn, is in housing finance. Latest figures on lending to non-first home buyers show activity was 10.4 per cent lower than the state’s decade average.

While multi-unit dwelling commencements in WA were 14.3 per cent higher than the decade average in WA,

these kinds of starts in other states and territories are outperforming their respective decade averages by a

much greater magnitude

TAS

Following eleven consecutive quarters entrenched in last place, Tasmania finally climbed two places to reach sixth on the housing league table. As suggested in the previous edition of Housing Scorecard, a slow grinding

recovery in Tasmania’s overall ranking is slowly taking place. In this edition, it’s sixth-place ranking due to the state increasing its overall state score by 10 points to reach 51.

Tasmania has finally relinquished the wooden spoon to South Australia and the Northern Territory.

The strong improvement in the Apple Isle was due largely to the strong results for both detached and multi-unit dwelling commencements. The latest level of these commencements outstripped the state’s decade average by 27.7 per cent and 145.9 per cent, respectively. This meant that Tasmania was the strongest state for multiunit dwelling commencements and the second strongest for detached dwelling commencements.

Conversely, the latest level of total private expenditure on alterations and additions – worth $155 million – was 18.0 per cent lower than the state’s decade average, representing the worst performance among the states and territories. While a last-place ranking isn’t ideal, at least it has been limited to this one indicator. In the previous edition of Housing Scorecard, Tasmania ranked the weakest state in five indicators.

However, there is still room for further improvement, with the performance of the majority of Tasmania’s housing indicators (nine out of fourteen) placed the state as the third weakest state among the eight state and territories, summarised in the table below.

NT

Conditions in the Northern Territory’s housing sector continue to deteriorate, evidenced by the territory’s

sliding ranking – down three places to rock bottom – in this edition of Housing Scorecard. The NT’s overall state score declined by 12 points to reach 49, which saw the territory share the wooden spoon with South Australia.

This weak score was due to bottom-place rankings (and thereby a score of only 1) in six of the fourteen indicators. Specifically, these indicators were: value of alterations and additions work approved; housing finance (among both first home and non-first home buyers); multi-unit dwelling approvals; multi-unit dwelling commencements, and; established house transfers. The latest performance of these indicators was at a level well below their respective decade averages.

Nevertheless, the NT’s construction labour market is still outperforming, with the latest size of, and hours worked by the construction labour force, more than 50 per cent above the decade average, the strongest performance among all the states and territories. Furthermore, while all signs are pointing towards a

substantial deterioration in the multi-unit segment of the new home building market, the detached segment of new home building is the bright spot for the NT’s overall housing sector. The latest number of detached houses that are under construction, having recently commenced construction, and also approved for construction are still well above decade averages, thereby rating the NT strongly compared with other jurisdictions on these measures

ACT

The Australian Capital Territory retained its mid-table ranking of fourth place in this Summer edition of Housing Scorecard, despite its score increasing by 2 points since the previous edition, to reach 63. Driving the increased score was the multi-unit segment of new home building – the latest levels of multi-unit

approvals as well as multi-unit commencements were 84.1 per cent and 60.3 per cent above their respective

decade averages. This represents a sharp turn-around from the performance in the previous edition, where

levels were tracking below their decade averages.

Fortunes can obviously change very quickly in the multiunit segment of the market – which could well be evident in coming editions of Housing Scorecard. Furthermore, not all multi-unit indicators outperformed in this update.

The latest level of multi-unit dwellings under construction was just shy of the ACT’s decade average (down by 0.4 per cent), while the level of attached dwelling transfers was down by 35.7 per cent.

While the multi-unit segment of the market looks to be set for a bumpy ride, the renovations market is looking brighter. The latest level of major alterations and additions work approved was 12.6 per cent above the decade average. While the value of total renovations expenditure was actually down from the decade average by 2.5 per cent, this is no comparison to the malaise in total renovations expenditure in most of the other states and territories.

Another bright spot is the reinvigorated first home buyer market, where the ACT ranks as the strongest jurisdiction for lending to first home buyers. The latest level of lending is some 6.7 per cent higher than the decade average.