We look at the latest ABS data in household income and wealth. And compare Australia with selected countries via World Bank data.

NOTE: Gini refers to the method in the analysis – it was a pun … sorry if it went over your head!

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

We look at the latest ABS data in household income and wealth. And compare Australia with selected countries via World Bank data.

NOTE: Gini refers to the method in the analysis – it was a pun … sorry if it went over your head!

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

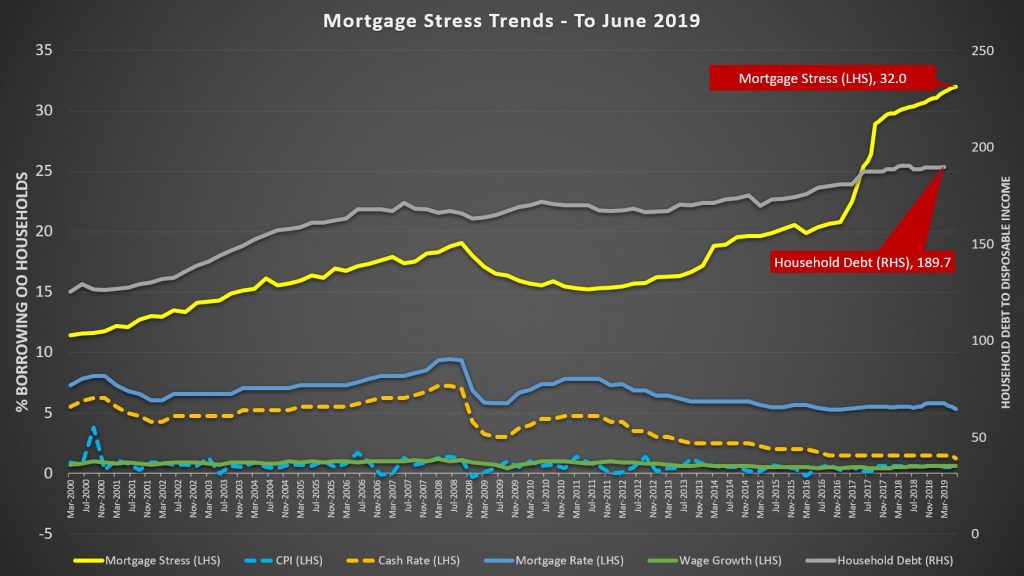

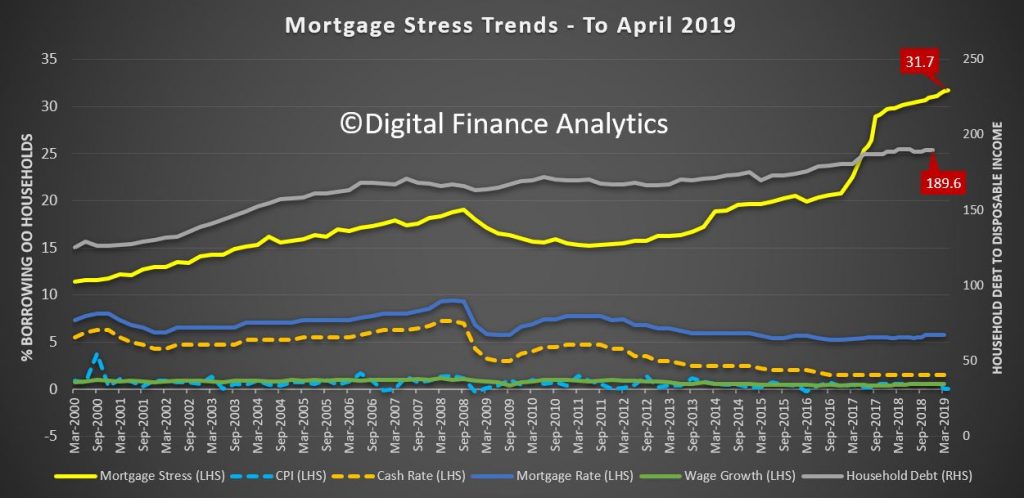

We review the latest data from the RBA, and the June results from our household surveys relating to mortgage stress.

See more at:

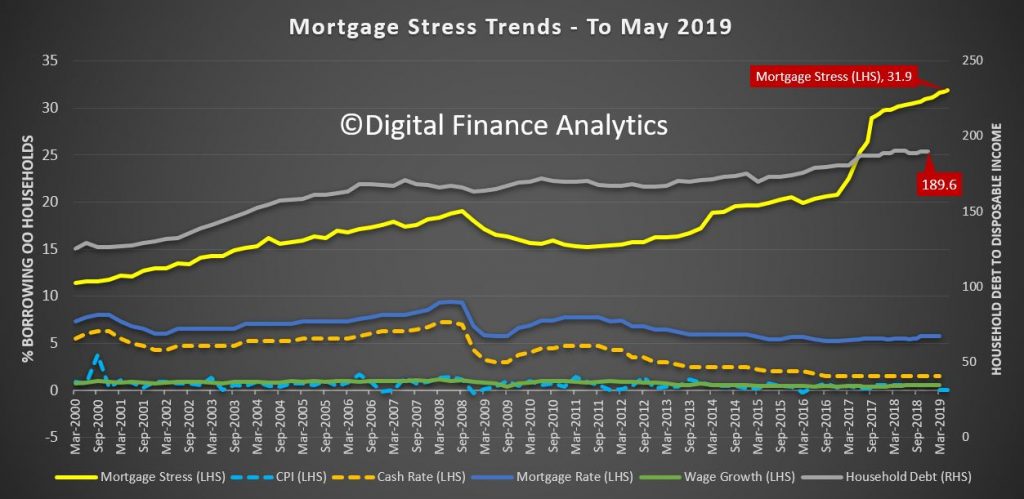

We have released the June 2019 mortgage stress results, based on our running 52,000 household surveys. We found that 32% of households are now dealing with mortgage stress, a record, meaning they are having cash flow issues managing their finances and mortgage repayments.

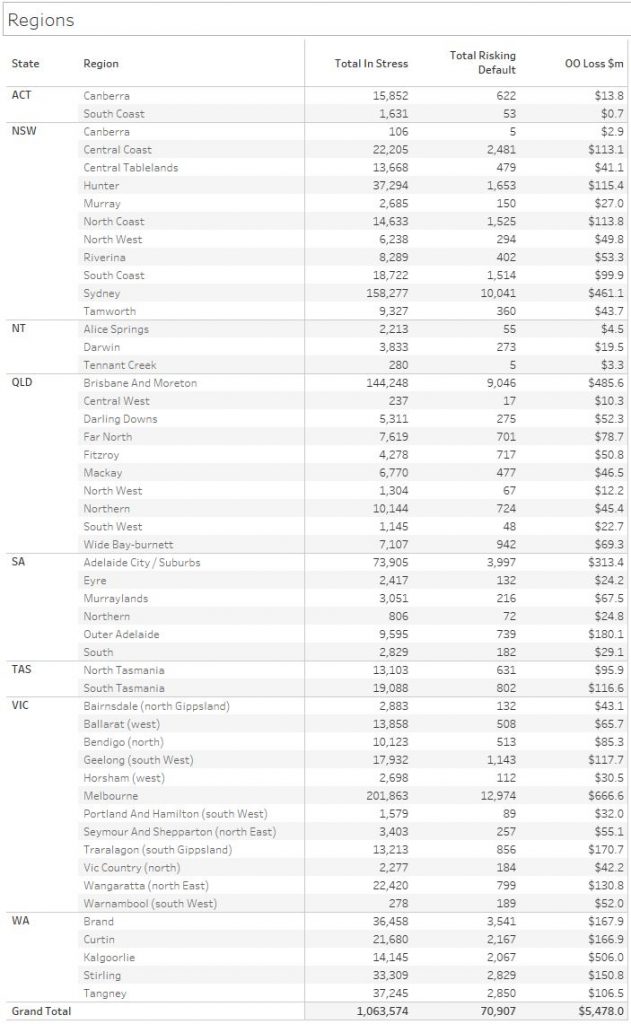

This translates into more than 1,063,000 households spread across the country, and nearly 71,000 risk default in the year ahead, even taking into account the fall in mortgage repayments represented by the recent rate cuts. Banks loses will rise.

This is because the costs of living continue to run ahead of incomes, while households have larger debts (and are being enticed to buy in the current complex risk environment).

The top post codes in stress are those in the outer suburban fringe areas, where many large estates are still being built, and households are super-highly leveraged.

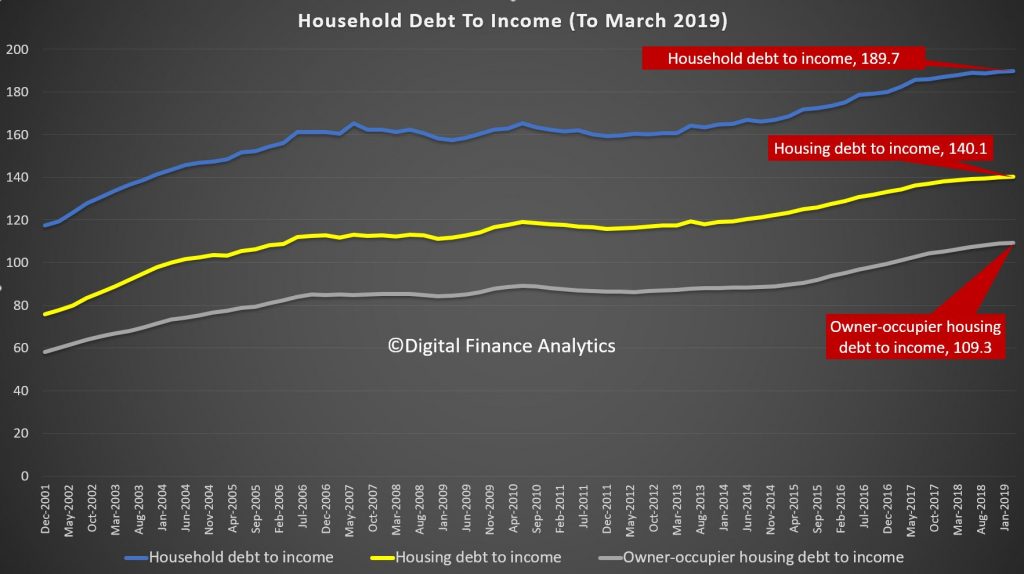

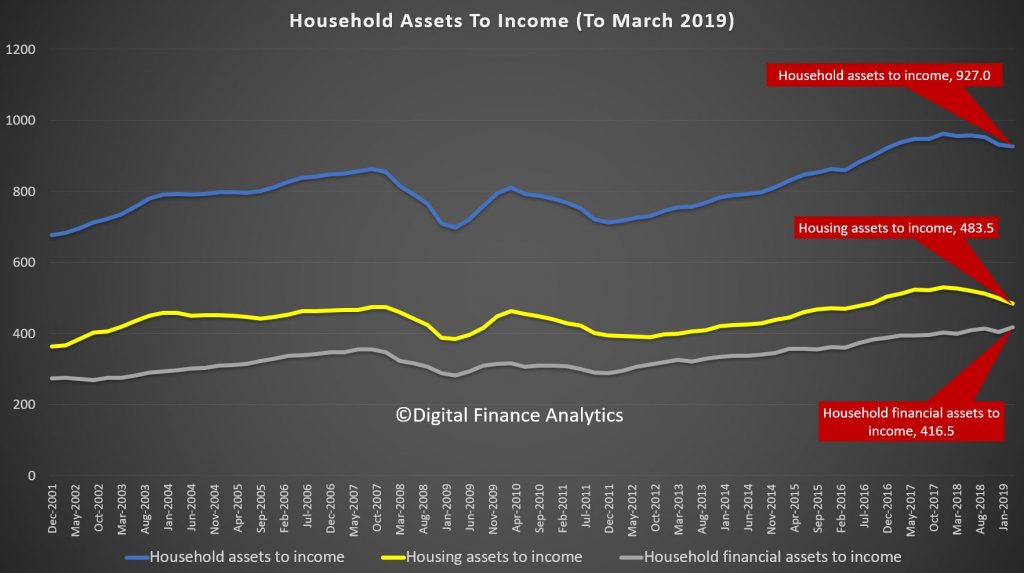

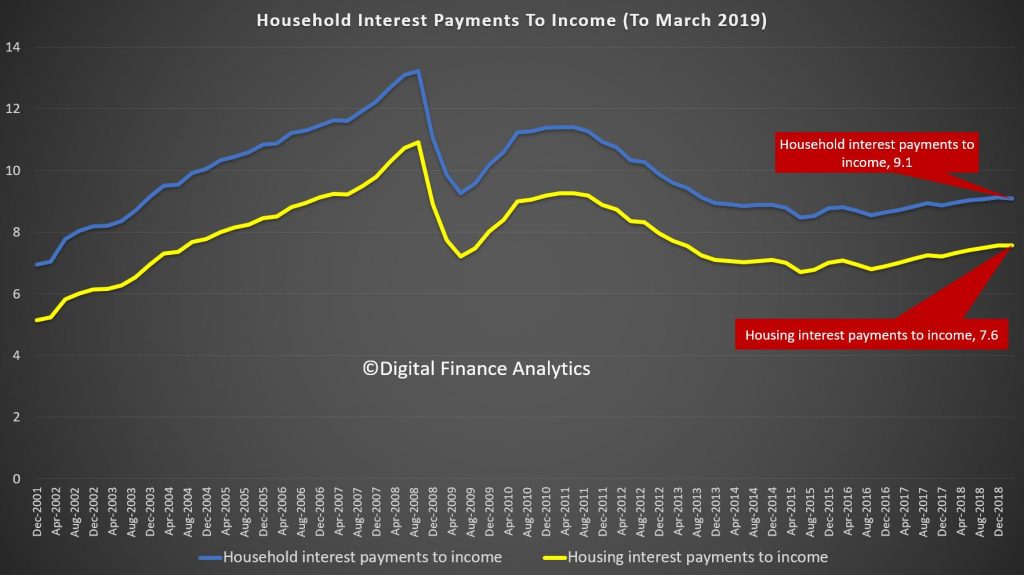

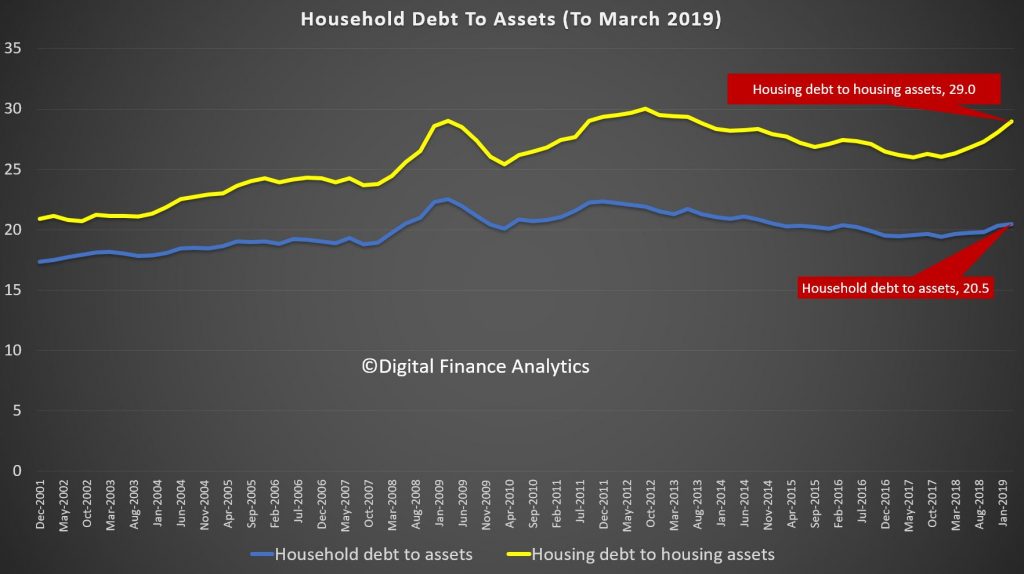

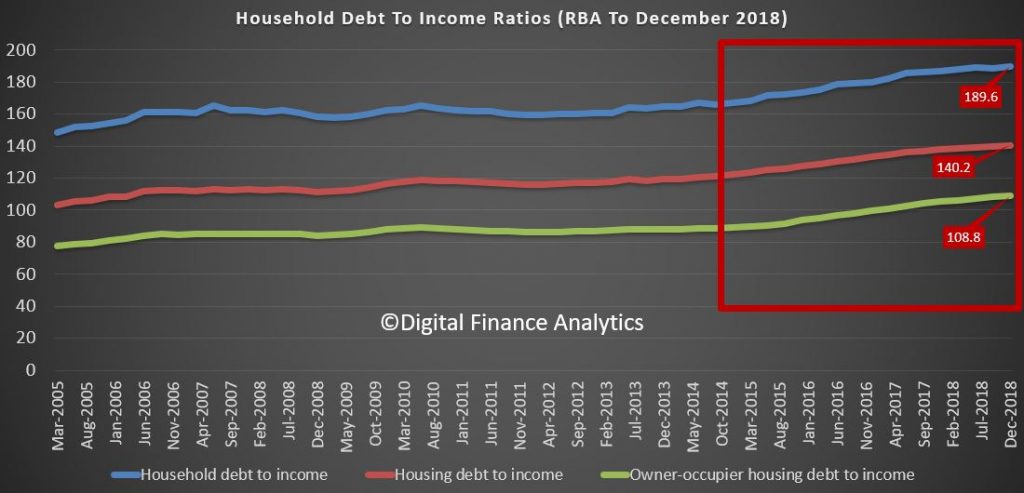

The RBA released their March 2019 data on household ratios. Whilst these series include small business finance, and include households not borrowing, the trends continue to tell the story of debt, and more debt.

The household debt to income ratio is at a record 189.7, while the housing debt to income ratio was 140.1, again a record and the owner occupied housing debt to income ratio was also up, to 109.3. These are high numbers, on a trend and international comparable basis. Households are drowning in debt.

However the asset to income ratios tell another story. As home prices have fallen, so the ratio has decreased, assets are down relative to income. The exception are financial assets, which benefited from the rise in stock prices this year.

The ratio of interest to income continues to rise because households are borrowing at a faster rate than their incomes are growing, helped of course by lower interest rates. This ratio is below that before the GFC because rates have dropped. And this is the one ratio spruikers turn to to defend the high debt levels – but it is myopic, and going in the wrong direction.

Finally, the RBA data debt to assets shows the pincer movement as home prices fall, and debt rises. This is now heading towards the highest we have seen.

The obvious conclusion is that the debt burden is too great, mortgage stress will go on rising, until the balance between debt and income is restored.

The recent loosening of lending standards simply pours more fuel on the fire. Households are being used a canon fodder in the vein attempt to keep the faltering economy afloat.

We mark the 20,000 subscriber count on YouTube, and also discuss the latest consumer sentiment.

Thanks to all those who support our efforts!

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) has released the May 2019 mortgage stress and default analysis update. Perhaps the rate cuts, rise to the minimum wage, and tax cuts ahead may turn the tide, but so far none of this matters for current household budgets. On the other hand more lending may make budgets even tighter if standards are dropped further.

Once again, it’s the continuing story of pressure on households as ongoing wages growth is not offsetting costs of living, and mortgage repayments as total debt continues to rise. Moreover, the trends have continued post the election.

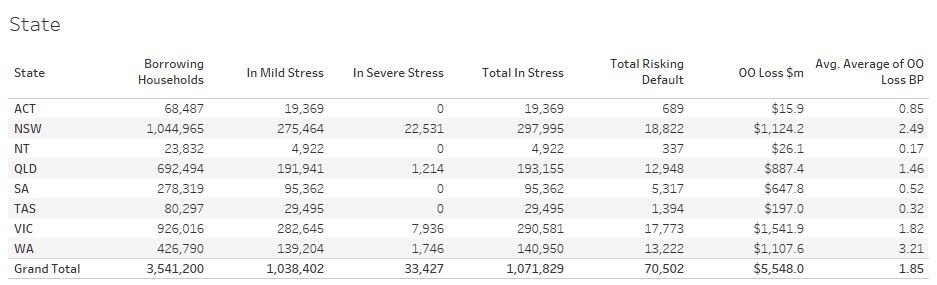

Across Australia, more than 1,071,829 households are estimated to be now in mortgage stress (last month 1,050,450), another new record. This equates to more than 31.9% of owner-occupied borrowing households. In addition, more than 33,427 (30,413 last month) of these are in severe stress. We estimate that more than 70,502 (last month 70,149) households’ risk 30-day default in the next 12 month. This is as the impact of flat wages growth, rising living costs and higher real mortgage rates hit home. Bank losses are likely to rise a little ahead.

Our analysis uses the DFA core market model which combines information from our 52,000 household surveys, public data from the RBA, ABS and APRA; and private data from lenders and aggregators. The data is current to the end of May 2019. We analyse household cash flow based on real incomes, outgoings and mortgage repayments, rather than using an arbitrary 30% of income.

Households are defined as “stressed” when net income (or cash flow) does not cover ongoing costs. They may or may not have access to other available assets, and some have paid ahead, but households in mild stress have little leeway in their cash flows, whereas those in severe stress are unable to meet repayments from current income. In both cases, households manage this deficit by cutting back on spending, putting more on credit cards and seeking to refinance, restructure or sell their home. Those in severe stress are more likely to be seeking hardship assistance and are often forced to sell.

Martin North, Principal of Digital Finance Analytics says that now the election results are known, and the dust has settled, we are still seeing the pressures on households are rising, thanks to an accumulation of larger mortgages compared to income whilst costs are rising, and incomes remain static. Housing credit growth is still running significantly faster than incomes and inflation and continued rises in living costs – notably child care, healthcare costs, school fees and electricity prices are causing significant pain. Many households are depleting their savings to support their finances or are trying to refinance.

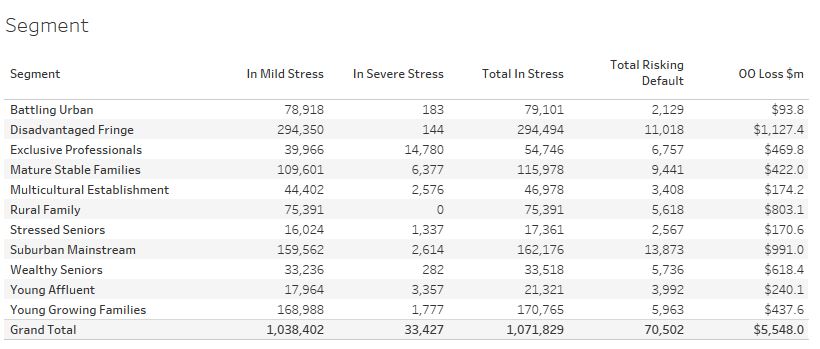

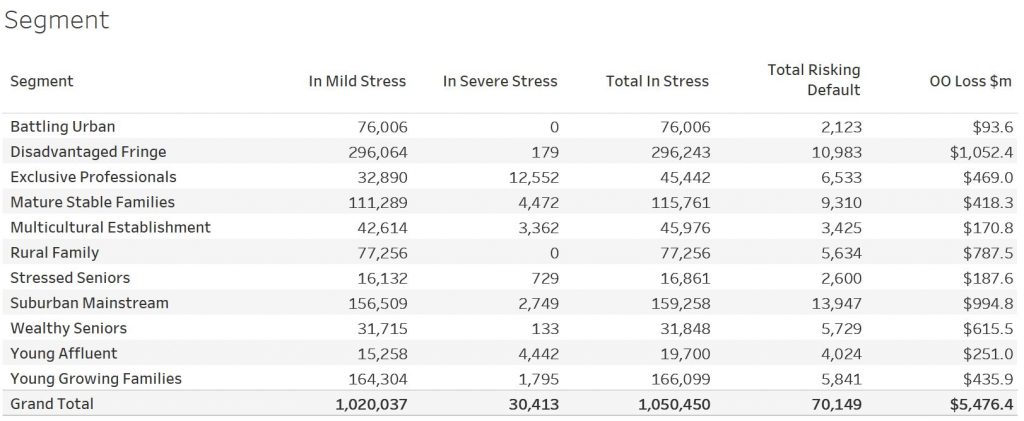

Probability of default extends our mortgage stress analysis by overlaying economic indicators such as employment, future wage growth and cpi changes. Our Core Market Model also examines the potential of portfolio risk of loss in basis point and value terms. Losses are likely to be higher among more affluent households, contrary to the popular belief that affluent households are well protected. This is shown in the segment analysis below:

Stress by the numbers.

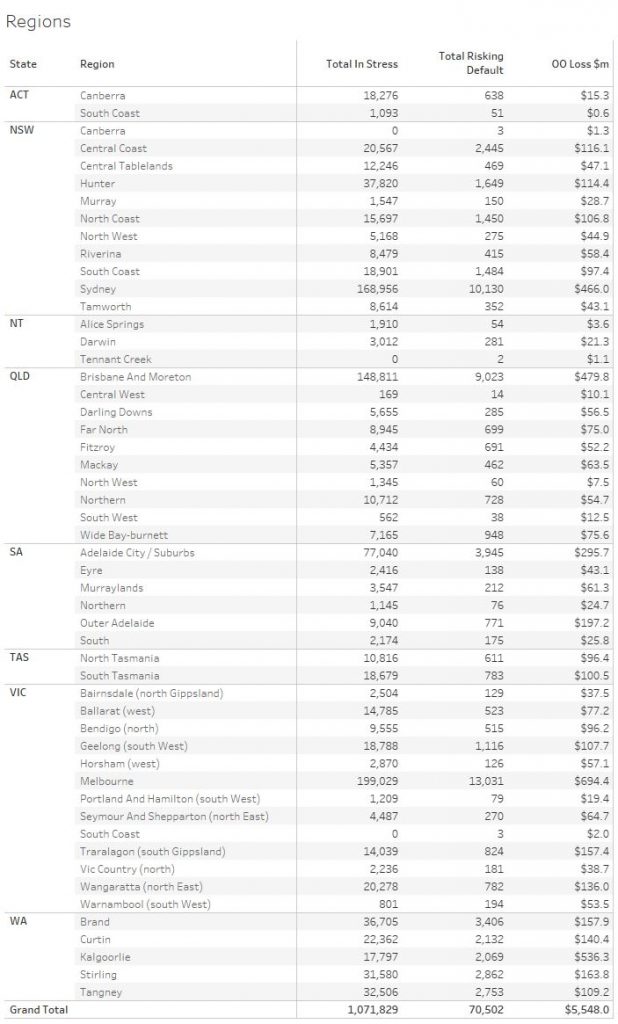

Regional analysis shows that NSW has 297,995 households in stress (284,014 last month), VIC 290,581 (292,114 last month), QLD 193,155 (184,037 last month) and WA has 140,950 (140,836) last month). The probability of default over the next 12 months rose, with around 13,222 (13,135 last month) in WA, around 12,948 (12,936 last month) in QLD, 17,773 (17,611 last week) in VIC and 18,822 (18,703 last month) in NSW.

The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.1 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($1.54 billion), though losses are likely to be highest in WA at 3.1 basis points, which equates to $1,107 million.

A fuller regional breakdown is set out below.

Here are

the top postcodes sorted by number of households in mortgage stress.

Handling Mortgage Stress

Households who are in financial difficulty should not ignore the signs. Though many do. And trying to refinance to solve the problem often ends up just postponing the inevitable.

We think there are some simple steps households can take:

Step one is to draw up a budget, so you can see where the money is coming and going. From our research, only half of households have any budget. This means you can then make decisions about what is most important, and what can be foregone. Select and prioritise.

Step two is to talk with your lender, as they have a legal obligation to assist is case of hardship. Yet many households avoid having that conversation, hoping the problem will cure itself. I have to say, in the current low-income growth, high cost environment, that is unlikely. And remember rates are likely to rise at some point.

Step three. Work out what would happen if mortgage rates rose by say half or one percent. Pass that across your budget and examine the impact. Then you will really know where you stand. Then plan accordingly.

You can request our media release. Note this will NOT automatically send you our research updates, for that register here.

[contact-form to=’mnorth@digitalfinanceanalytics.com’ subject=’Request The May 2019 Stress Release’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email Me The May 2019 Media Release’ type=’radio’ required=’1′ options=’Yes Please’/][contact-field label=”Comment If You Like” type=”textarea”/][/contact-form]

Note that the detailed results from our surveys and analysis are made available to our paying clients.

I discuss the current economic settings and expectations for future rate cuts and home prices on 6PR Perth with Gareth Parker.

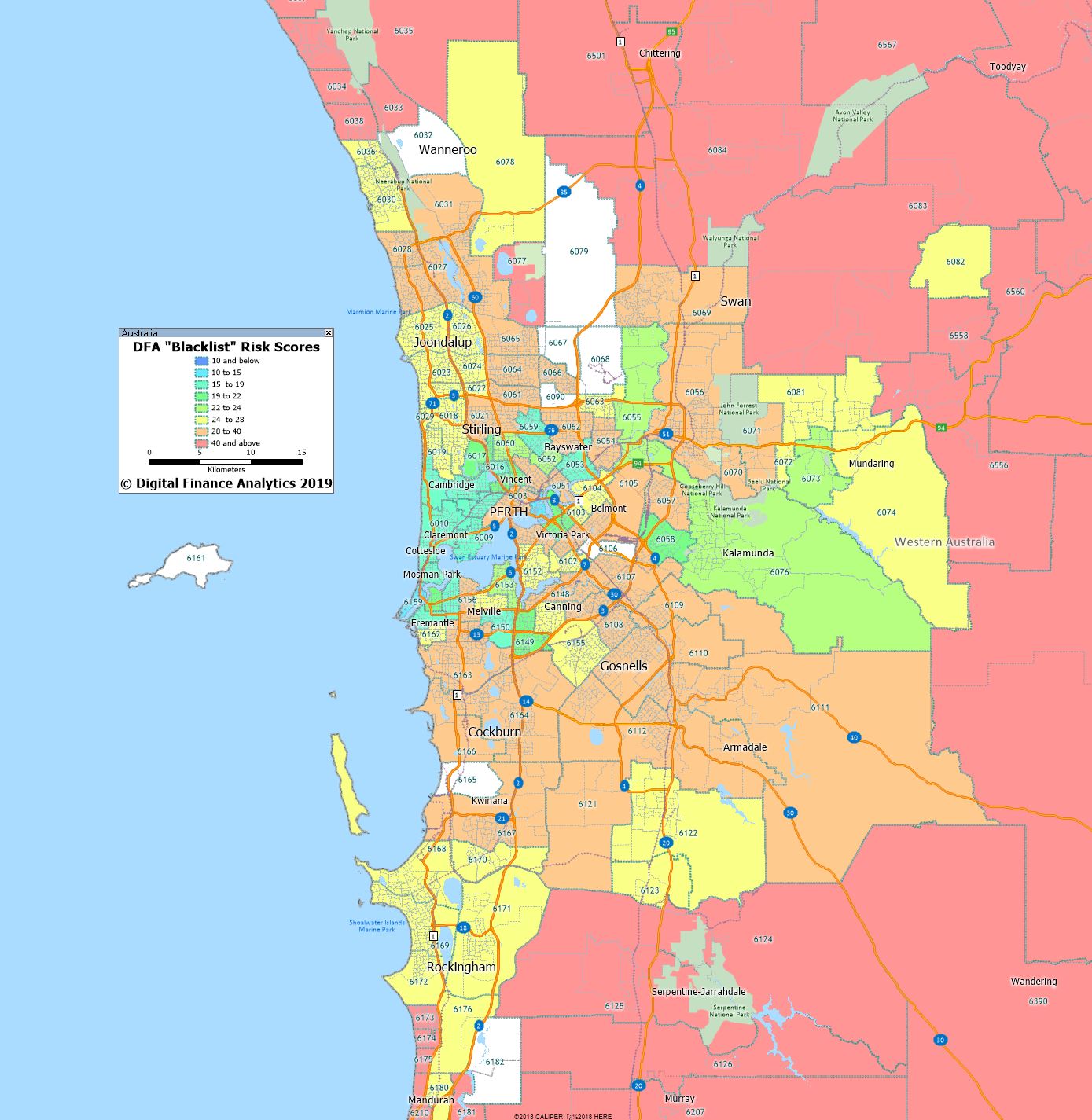

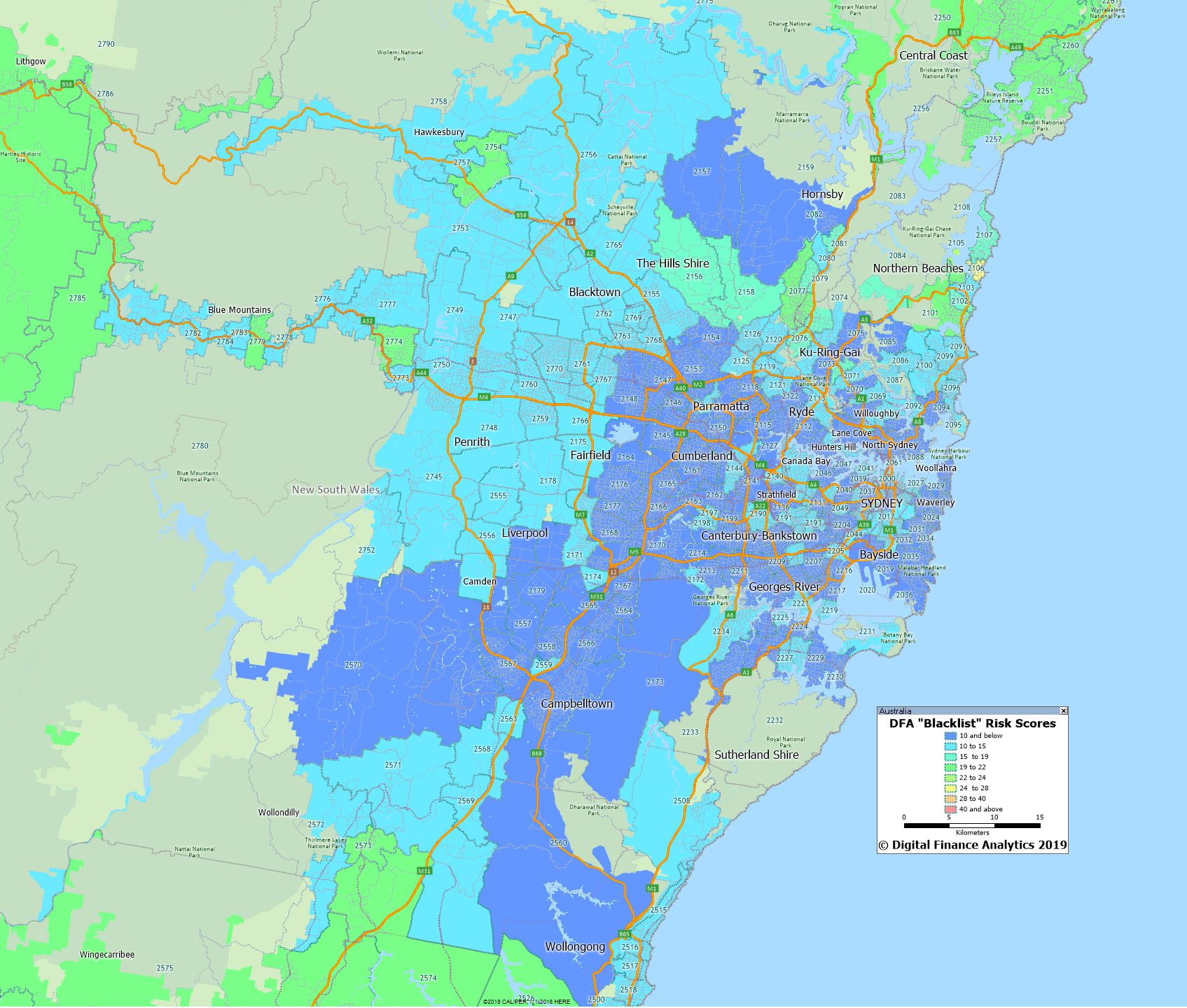

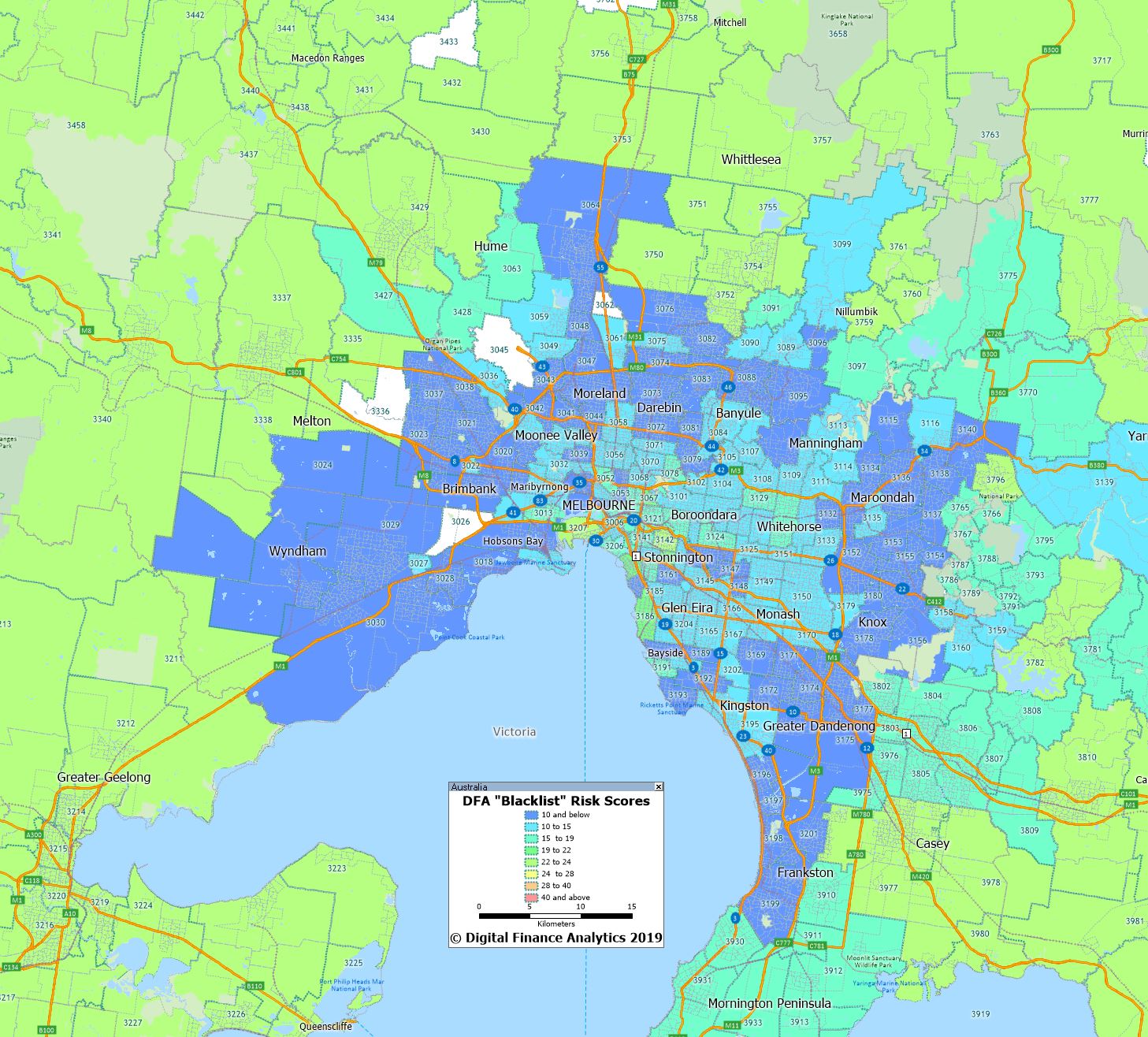

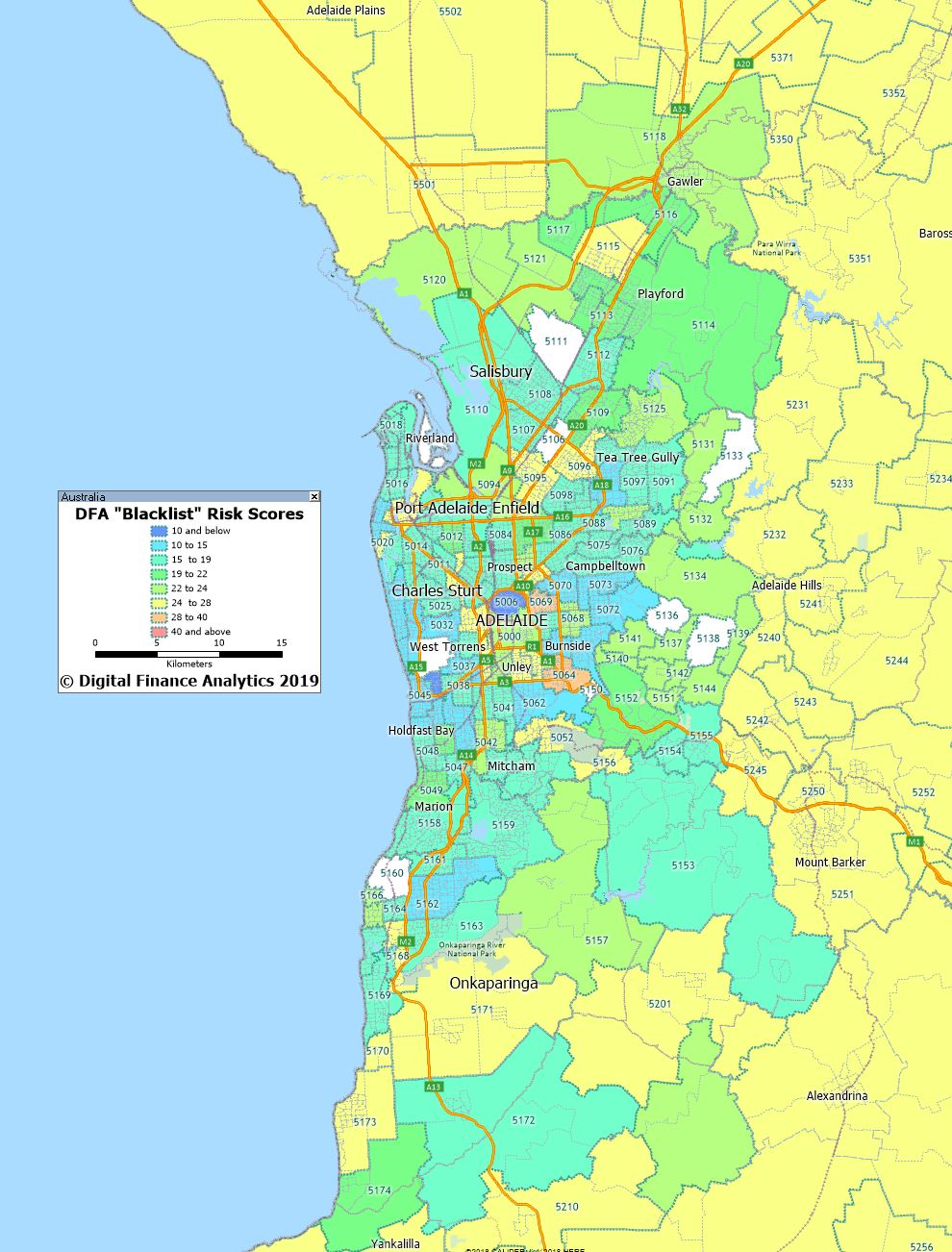

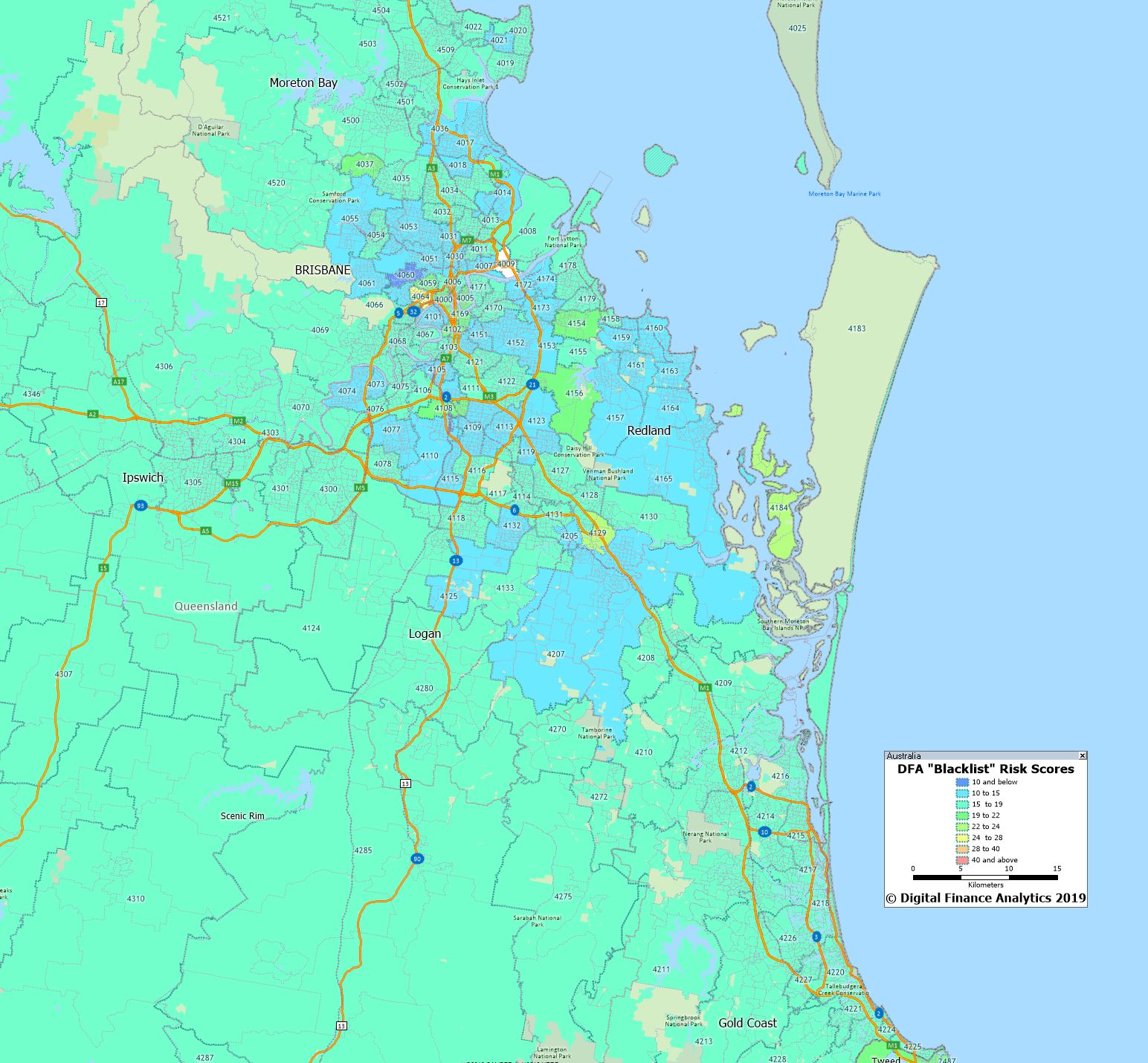

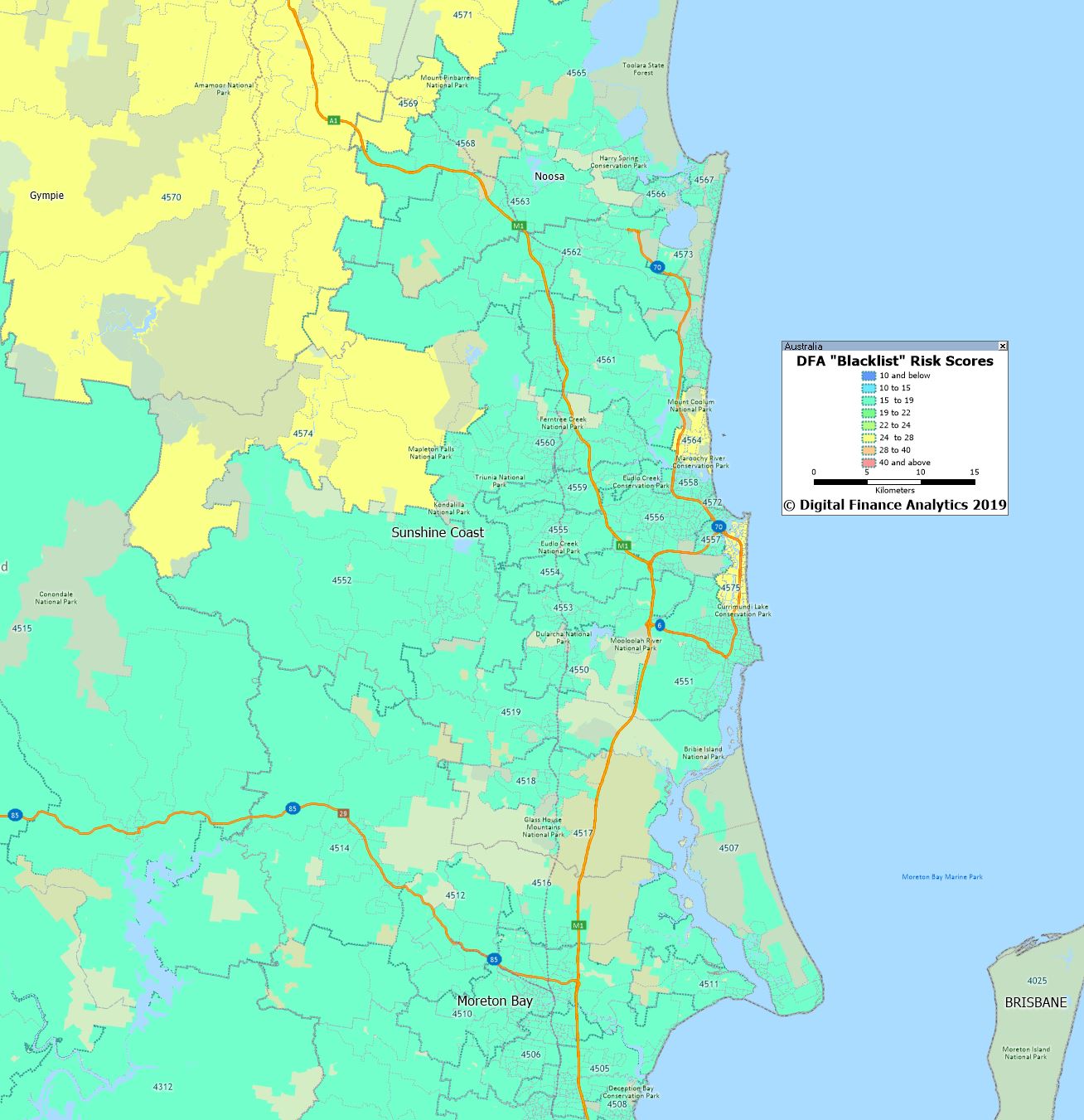

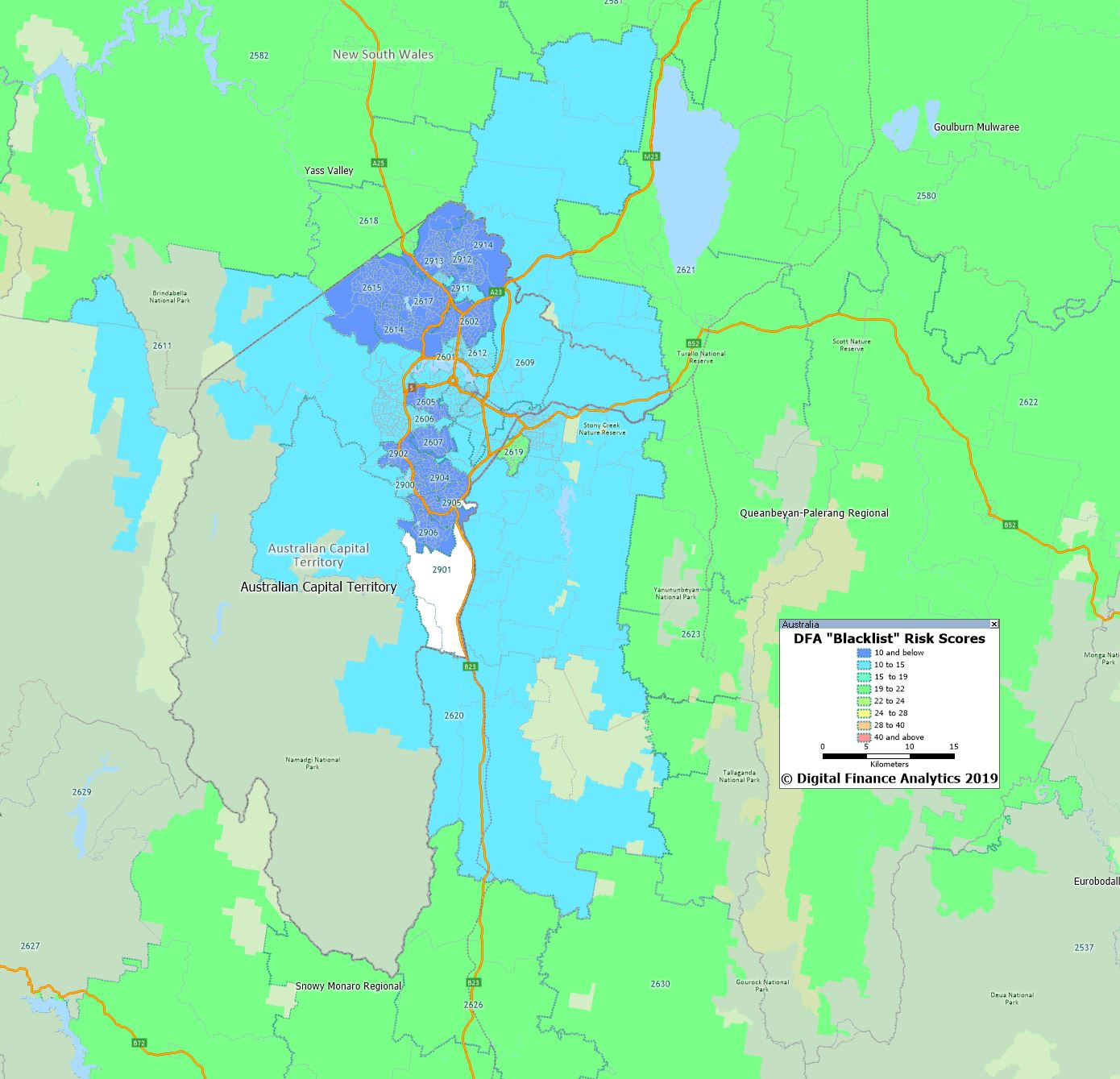

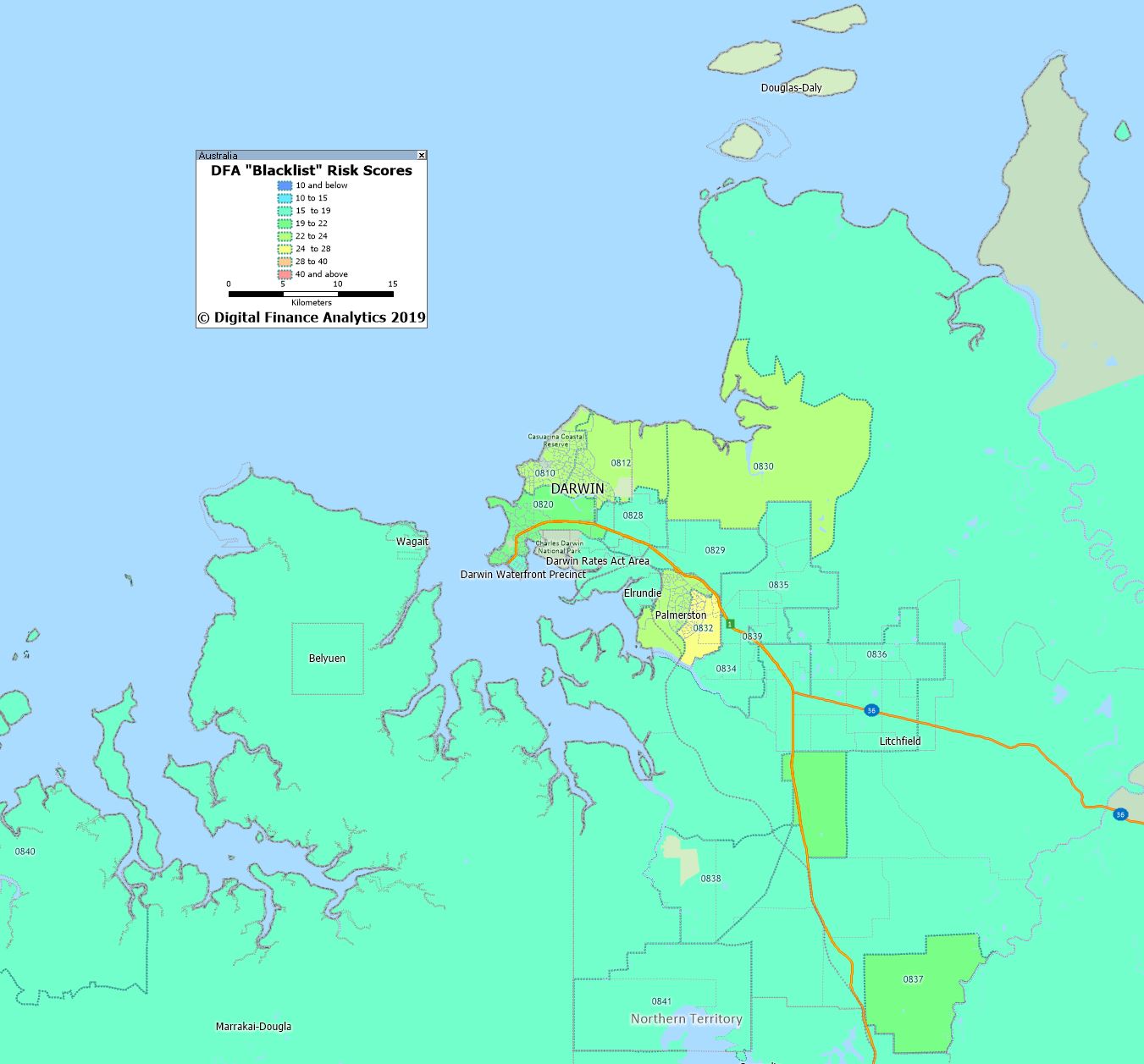

DFA has developed a risk scoring system, which combines information from lenders, and households to provide an indicator of the relative likelihood of an applicant successfully obtaining a mortgage, within a specific post code, and the relative weighting in terms of loan-to-value (LVR) and other factors which will be taken into account.

Additional factors will also include the mix between high-rise and low-rise development (some banks have blacklisted certain development types in some suburbs), and recent home price moves.

On the DFA Blacklist scale, the higher the score, the greater the difficulty in obtaining finance. In practice, this also reflects the relative risks of mortgage stress and default, and is also subject to an economic overlay in terms of relative economic performance and household finances. This was featured in an ABC piece last week. It is not predicative, rather it reflects current behaviour and past risk.

While individual household scores will vary, an average post code score above 15 represent higher than normal risk, meaning many lenders will require a larger deposit, or may prefer not to lend at all. The higher the score, the greater the difficulty in getting finance.

Since I have received many requests for more information, today we are releasing more complete mapping, which is up to the end of April 2019.

The maps are presented in native high resolution. The blue shades are low scoring post codes. Red shows highest scores.

Western Australia, as represented by the area around Perth is by far the most blacklisted region.

In comparison Sydney scores are lower, though with some hot spots.

Melbourne also shows a few hot spots.

Adelaide has some risk areas.

Brisbane and the Gold Coast are fairing quite well (but again, with some hot spots).

The Sunshine Coast is more problematical.

The ACT scored pretty low.

While Darwin was more problematic, reflecting the significant falls in values in recent years, and the economic conditions there.

To emphasise the point, individual lenders and borrowers circumstances will vary, but our analysis does highlight that not all post codes are born equally when it comes to mortgage applications.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) has released the April 2019 mortgage stress and default analysis update. Once again, it’s the continuing story of pressure on households as ongoing wages growth is not offsetting costs of living, and mortgage repayments and total debt continues to rise. Recent bank reporting highlights the elevated risks in the household sector as this all plays out.

The latest RBA data on household debt to income to December rose to 189.6[1], and remains highly elevated. Plus, the housing debt ratio continues to climb to a new record of 140.2, according to the RBA. This shows that household debt to income is still increasing.

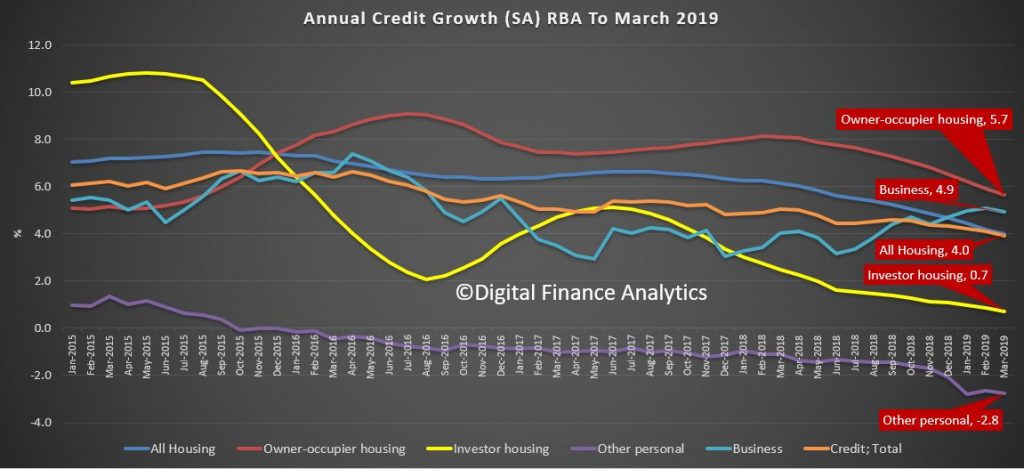

This is confirmed by the latest financial aggregates to end March recently released by the RBA, with owner occupied lending still growing significantly faster than inflation at 5.7%.

This high debt level, in the context of broader financial pressure, helps to explain the fact that mortgage stress continues to rise.

Across Australia, more than 1,050,450 households are estimated to be now in mortgage stress (last month 1,044,666), another new record. This equates to more than 31.7% of owner-occupied borrowing households. In addition, more than 30,413 (27,775 last month) of these are in severe stress. We estimate that more than 70,149 (last month 66,700) households’ risk 30-day default in the next 12 month. This is as the impact of flat wages growth, rising living costs and higher real mortgage rates hit home. Bank losses are likely to rise a little ahead.

Our analysis uses the DFA core market model which combines information from our 52,000 household surveys, public data from the RBA, ABS and APRA; and private data from lenders and aggregators. The data is current to the end of April 2019. We analyse household cash flow based on real incomes, outgoings and mortgage repayments, rather than using an arbitrary 30% of income.

Households are defined as “stressed” when net income (or cash flow) does not cover ongoing costs. They may or may not have access to other available assets, and some have paid ahead, but households in mild stress have little leeway in their cash flows, whereas those in severe stress are unable to meet repayments from current income. In both cases, households manage this deficit by cutting back on spending, putting more on credit cards and seeking to refinance, restructure or sell their home. Those in severe stress are more likely to be seeking hardship assistance and are often forced to sell.

Despite reassurances that household finances are fine, the pressures are rising, thanks to an accumulation of larger mortgages compared to income whilst costs are rising, and incomes remain static. Housing credit growth is still running significantly faster than incomes and inflation and continued rises in living costs – notably child care, healthcare costs, school fees and electricity prices are causing significant pain. Many households are depleting their savings to support their finances or are trying to refinance.

Probability of default extends our mortgage stress analysis by overlaying economic indicators such as employment, future wage growth and cpi changes. Our Core Market Model also examines the potential of portfolio risk of loss in basis point and value terms. Losses are likely to be higher among more affluent households, contrary to the popular belief that affluent households are well protected. This is shown in the segment analysis below:

Stress by the numbers.

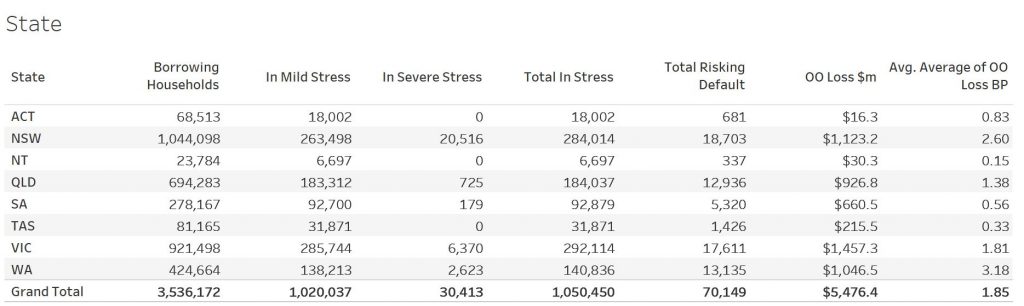

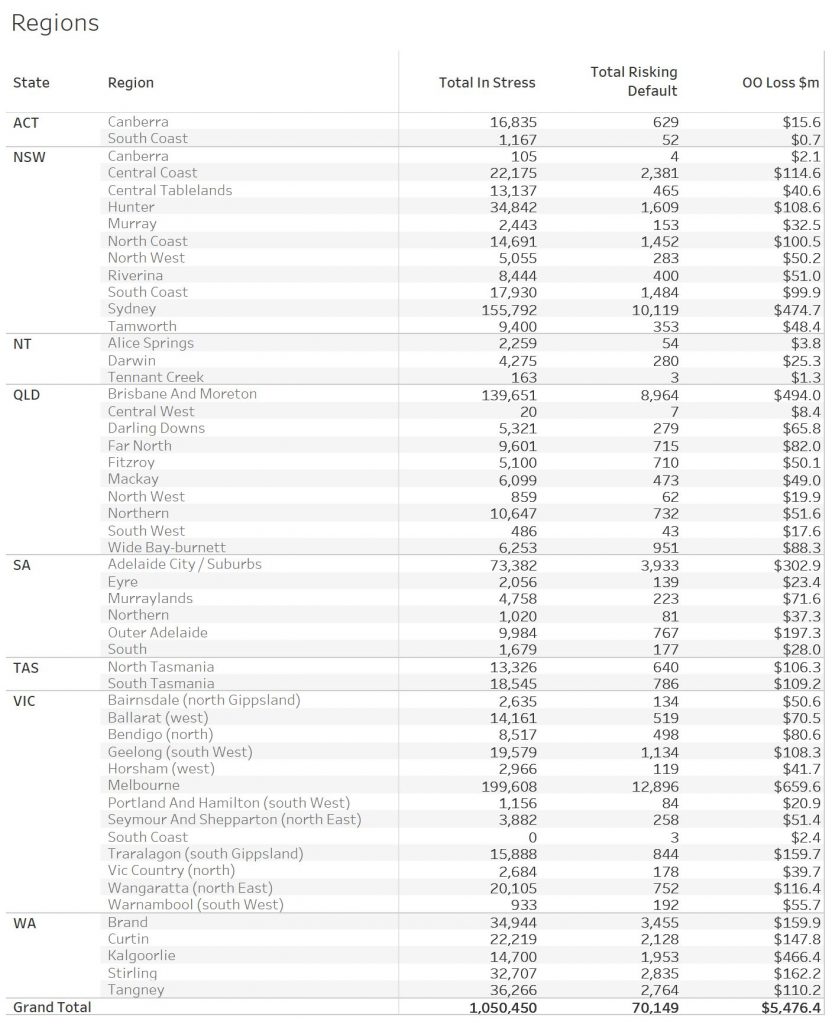

Regional analysis shows that NSW has 284,014 households in stress (286,890 last month), VIC 292,114 (283,753 last month), QLD 184,037 (185,282 last month) and WA has 140,836 (141,199 last month). The probability of default over the next 12 months rose, with around 13,135 (12,600 last month) in WA, around 12,936 (12,400 last month) in QLD, 17,611 (16,700 last week) in VIC and 18,703 (17,700 last month) in NSW.

The largest financial losses relating to bank write-offs reside in NSW ($1.1 billion) from Owner Occupied borrowers) and VIC ($1.46 billion) from Owner Occupied Borrowers, though losses are likely to be highest in WA at 3.1 basis points, which equates to $1,046 million from Owner Occupied borrowers.

Here is a regional breakdown.

Here are the top postcodes sorted by number of households in mortgage stress.

Handling Mortgage Stress

Households who are in financial difficulty should not ignore the signs. Though many do. And trying to refinance to solve the problem often ends up just postponing the inevitable.

We think there are some simple steps households can take:

Step one is to draw up a budget, so you can see where the money is coming and going. From our research, only half of households have any budget. This means you can then make decisions about what is most important, and what can be foregone. Select and prioritise.

Step two is to talk with your lender, as they have a legal obligation to assist is case of hardship. Yet many households avoid having that conversation, hoping the problem will cure itself. I have to say, in the current low-income growth, high cost environment, that is unlikely. And remember rates are likely to rise at some point.

Step three. Work out what would happen if mortgage rates rose

by say half or one percent. Pass that across your budget and examine the

impact. Then you will really know where you stand. Then plan accordingly.

[1] RBA E2 Household Finances – Selected Ratios December 2018

You can request our media release. Note this will NOT automatically send you our research updates, for that register here.

[contact-form to=’mnorth@digitalfinanceanalytics.com’ subject=’Request The April 2019 Stress Release’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email Me The April 2019 Media Release’ type=’radio’ required=’1′ options=’Yes Please’/][contact-field label=”Comment If You Like” type=”textarea”/][/contact-form]

Note that the detailed results from our surveys and analysis are made available to our paying clients.

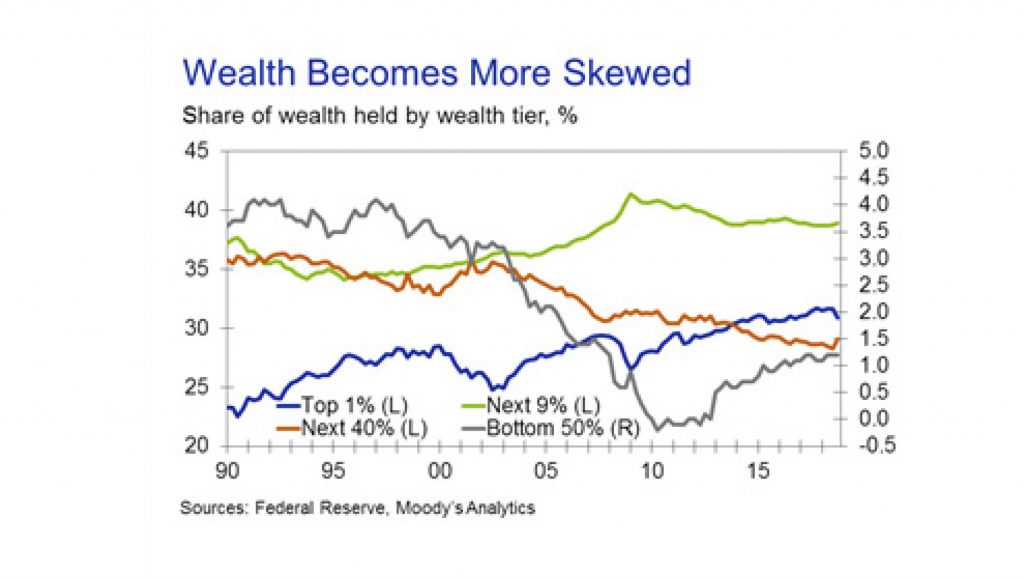

Moody’s says that inequality has been increasing in the U.S. for decades. This has been well-documented. However, new data from the Federal Reserve shed additional light on the distribution of wealth and how it has evolved over time. The Distributional Financial Accounts show levels and share of wealth across four segments of the wealth distribution: the top 1%, the next 9%, the rest of the top half, and the bottom half. This is done by sharing out household wealth as shown in the Financial Accounts using primarily the Survey of Consumer Finances, supplemented with other information in some instances.

The data clearly show the skewed distribution of wealth. The most recent data, for the fourth quarter of last year, show that the wealthiest 1% of households held 30.9% of total household wealth, only marginally below the record high of 31.7% a year earlier and well above the 1990 low of 22.5%. By contrast, the bottom half of the wealth distribution holds only 1.2% of all wealth, down from over 4% at points during the 1990s. However, it is better than the period immediately after the Great Recession, when this group was in debt in aggregate.

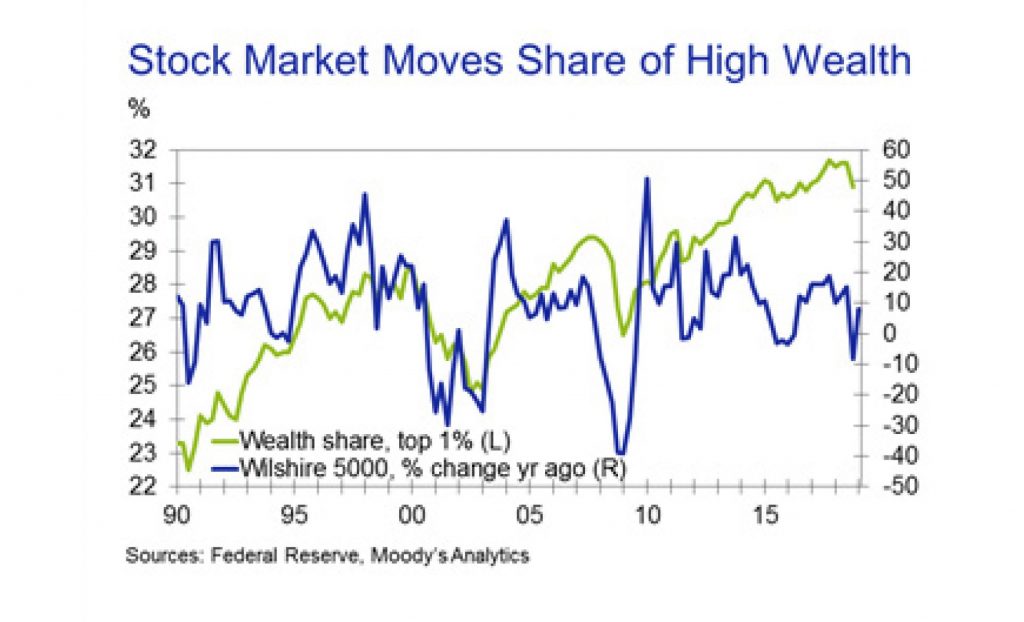

One clear feature of the data is that the distribution of wealth doesn’t change in a linear fashion. The share of wealth held by the richest 1% has declined at times, and in some cases sharply. For example, the share topped 28% at the start of 2000 before falling under 25% in late 2002. Similarly, the share fell from 29.4% in late 2007 to 26.5% in early 2009. Both declines corresponded with sharp declines in U.S. stock prices.

Ownership of stocks is heavily skewed toward the high end of the income and wealth distribution. Hence, the stock market is a strong driver of the share of wealth held by the richest households. The extent of the correlation may be surprising.

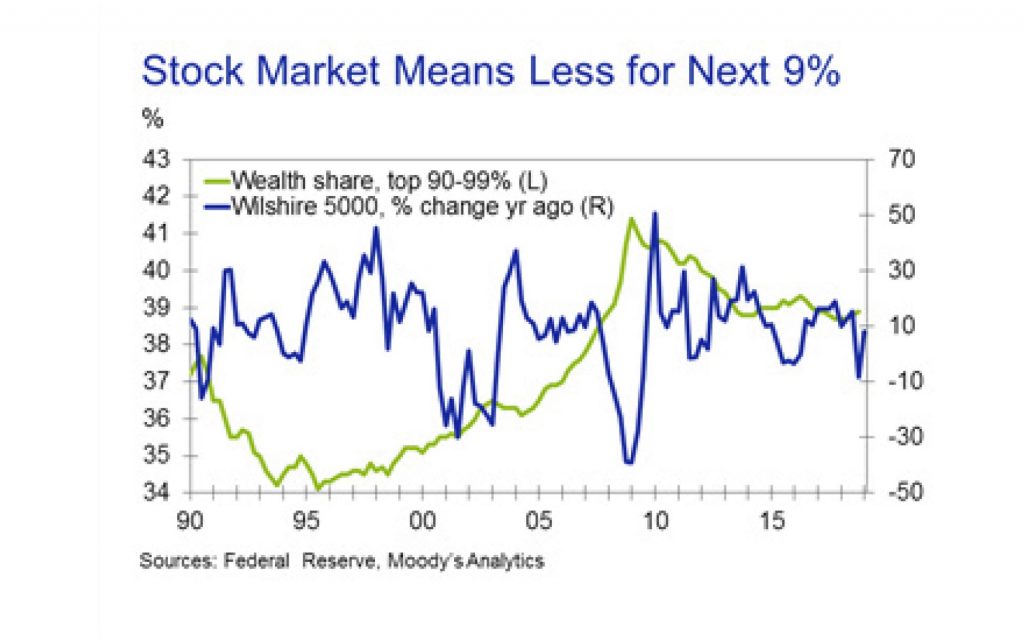

More interesting, the correlation largely breaks down for the next richest 9% of the population. Their share of wealth fell in the early 1990s, then rose steadily until the Great Recession before trending lower. While there is some correlation with movements in stock prices, they are clearly not the dominant driver they are for the richest households. This emphasizes how skewed wealth related to equity prices is.

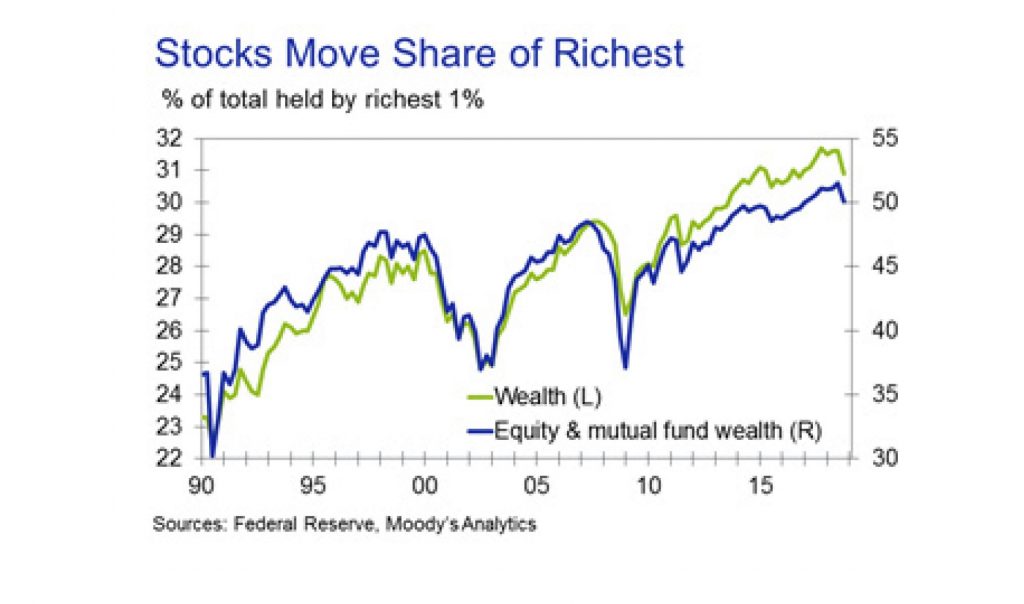

To drive home the point, the correlation between the share of total wealth held by the richest 1% of households and the share of corporate equities and mutual fund shares held by the richest households is an astounding 94%. At present, equities and fund shares account for nearly 40% of wealth for this group of households. However, this share has grown dramatically over time. In the early 1990s it was under 20%, and over the entire history of the series it averages 30%.

This one component of wealth is the major driver of changes in share for the wealthiest households. Their share of wealth excluding stocks and mutual fund shares is about 4 percentage points lower on average, rises less, and is much more stable. This may understate the impact of equity prices on the wealth of these households, since equities are included in life insurance reserves and pension entitlements and correlate with equity in noncorporate businesses.

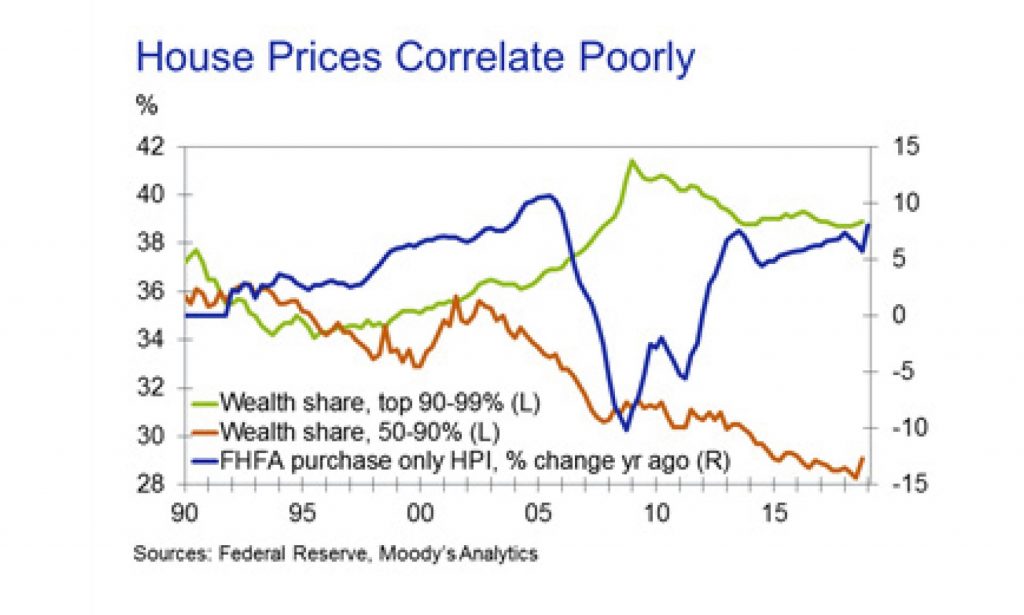

Other obvious candidates as drivers of changes in the wealth distribution fail to achieve anything like the apparent impact of equity markets. Despite making up a larger portion of household assets than corporate equities and mutual funds, housing wealth is less of a driver of wealth shares. Houses are more commonly owned, and, other than around the Great Recession, movements in house price growth tend to be gradual. Even for the lower-wealth households, where real estate would be their primary asset, there seems little linkage between house price growth and those households’ share of total wealth. Similarly, the link between unemployment and wealth shares is weak.

The differences in the makeup of household balance sheets at different positions in the wealth distribution are also shown in the distributional accounts data. This is one of the driving factors in the share movements. Therefore, it should not be surprising that corporate equities and mutual funds are most important for the richest households. They account for over a third of assets for the wealthiest 1% of households, compared with about a fifth for the next 9% of households, under 10% for the next 40% of households, and under 4% of assets for the bottom half of the wealth distribution. Equity in noncorporate business is similarly skewed heavily toward wealthy households.

By contrast, real estate assets are the most important piece of the balance sheet for the bottom half of the wealth distribution. For this group, they account for about half of all assets. The share declines sharply as wealth increases until it falls below 12% of assets for the richest 1% of households.

Pension entitlements are an important component of the balance sheet for households in the upper half of the wealth distribution, excluding the very rich. They make up almost a third of assets for households in the 50th-90th percentiles of the distribution and about 30% for households in the top 10% excluding the top 1%. However, they make up less than 10% of assets for the very wealthy and bottom half of the distribution. Most likely, lower-wealth households don’t have pensions while pensions for the very wealthy are swamped by other assets. Pension entitlements are important for future spending but may be less important for current spending if they are not well-understood.

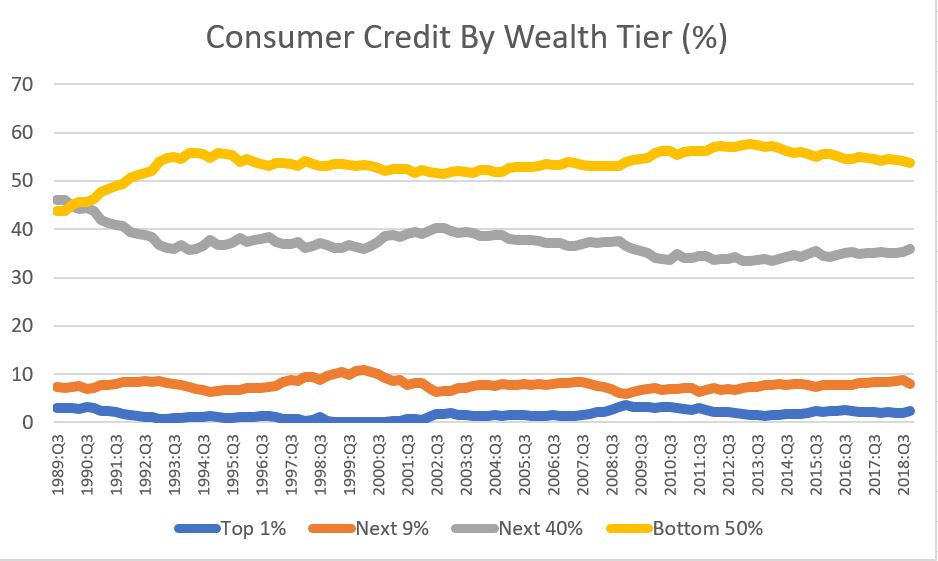

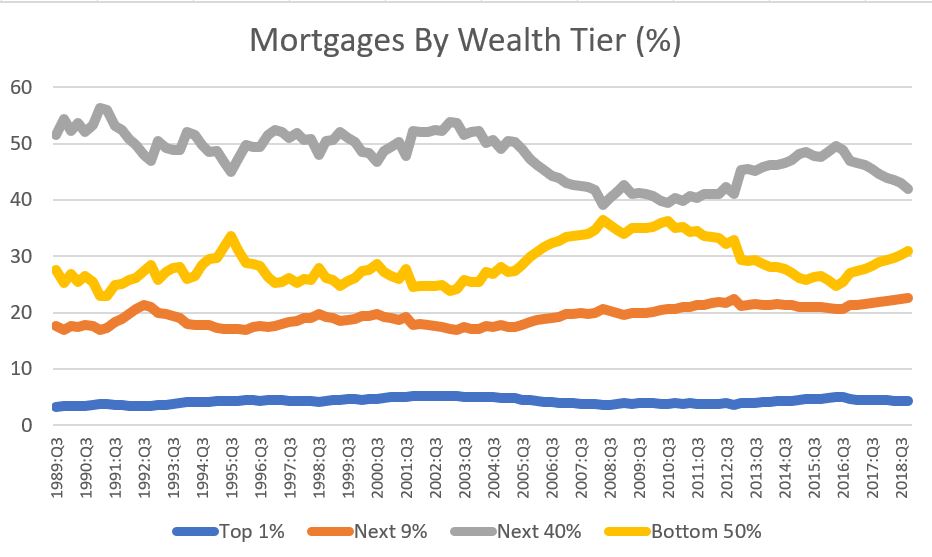

Liabilities follow what is probably an expected pattern. Mortgages account for a little over two-thirds of total household liabilities. However, they account for only a bit more than half of debt for households in the bottom half of the distribution. Consumer credit accounts for about 40% of their debt, the highest for any of the segments and well above the average of about a quarter.

The mortgage share increases until the top 1% of the distribution. They have nearly 15% of their debt in the other loans and advances category, dramatically more than other segments. This category captures debt related to their businesses and investments. Hence, just as real estate is a smaller portion of assets for the richest households, so too is mortgage debt a smaller share of liabilities.

The stock market has shown itself to be an important driver of the distributions of wealth. Current prospects are for the market to perform poorly by historical standards over the next year or so.

Economic growth is expected to slow and valuations remain high. Neither is favorable for the market.

The one silver lining in this is that weak stock market performance tends to associate with a moderation in wealth inequality.