Robo-Advice, the concept of using computer automation to provide tailored financial advice has been hitting the headlines recently. DFA has researched household demand for these digitally delivered services, and today we share some of the results.

By way of background, a robo-advisor is an online wealth management service that provides automated, algorithm-based portfolio management advice without the use human financial planners. Robo-advisors (or robo-advisers) use the same software as traditional advisors, but usually only offer portfolio management and do not get involved in more personal aspects of wealth management, such as taxes and retirement or estate planning. Robo-advisors are typically low-cost, have low account minimums, and attract younger investors who are more comfortable doing things online. The biggest difference is the distribution channel: previously, investors would have to go through a human financial advisor to get the kind of portfolio management services robo-advisors now offer, and those services would be bundled with additional services.

ASIC’s chairman Greg Medcraft says computer-generated financial advice, or “robo advice” could slash investment costs and eliminate conflicts of interest in the maligned financial planning industry. They have established a “robo-advice taskforce”, which is investigating the suitability of potential entrants, who use computer algorithms to match investors with suitable assets at a lower cost than human advisers.

A number of Australian players are experimenting with different offers and solutions. For example, according to the AFR, Macquarie is creating a robo-advice platform that puts in one place more than 30,000 local and international investment choices. Unlike other robo-advice platforms, which are really vehicles for gaining funds under management and charging an asset management fee, Macquarie has opted for genuine portfolio advice that does not discriminate between particular fund managers or show any bias towards particular stocks or sectors.

Midwinter’s “Robo-Advice Survey” from 2015, which comprised of responses from over 288 advice professionals, representing over 65 licensees showed the majority of advisers (55%) surveyed were aware of Robo-Advice and not concerned about its potential to disrupt the advice industry, with 12% of these advisers actually excited about its arrival. Around a quarter of advisers were aware and concerned of the impact of Robo-Advice on their business. Only a small amount of advisers (5%) considered themselves apathetic towards the rise of Robo-Advice.

Fintech’s such as Decimal which was founded in 2006 by former Asgard senior executive Jan Kolbusz, provides new capability to the financial advice industry utilising the power and affordability of the cloud. Decimal has subsequently entered into an agreement with Aviva Corporation that saw the company listed on the ASX in April 2014 as Decimal Software Limited (DSX).

So turning to our analysis, DFA has been examining the prospective impact of Robo-Advice, from a household perspective using data from our household surveys. We have found that currently those who have received financial advice already, and who are most digitally aware would readily consider Robo-Advice services. Our conclusion is that rather than growing and extending advice to more Australian households, the first impact of Robo-Advice will be to cannibalise existing advisor relationships.

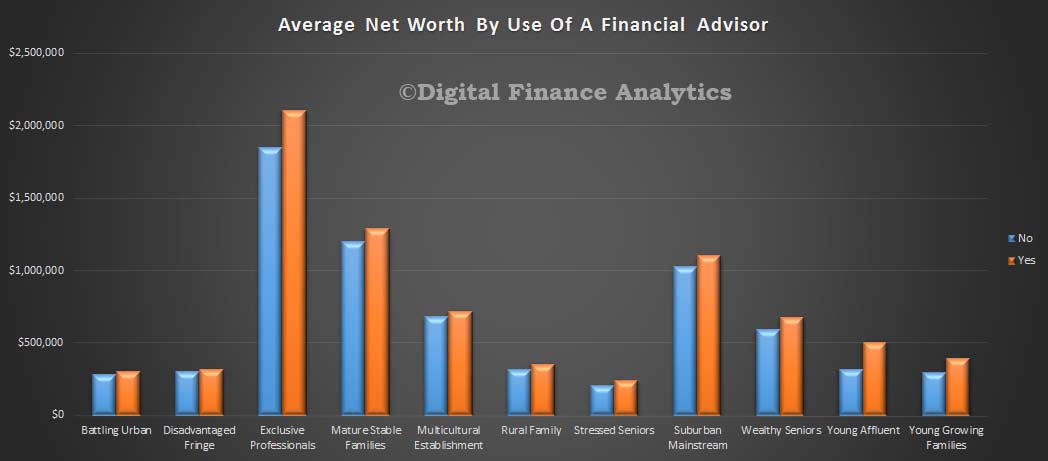

To start the analysis,we looked at overall estimated net worth by household segment. Those households with higher balances are more likely to have sought, or are seeking financial advice. On average a quarter of households have at some time sought advice.

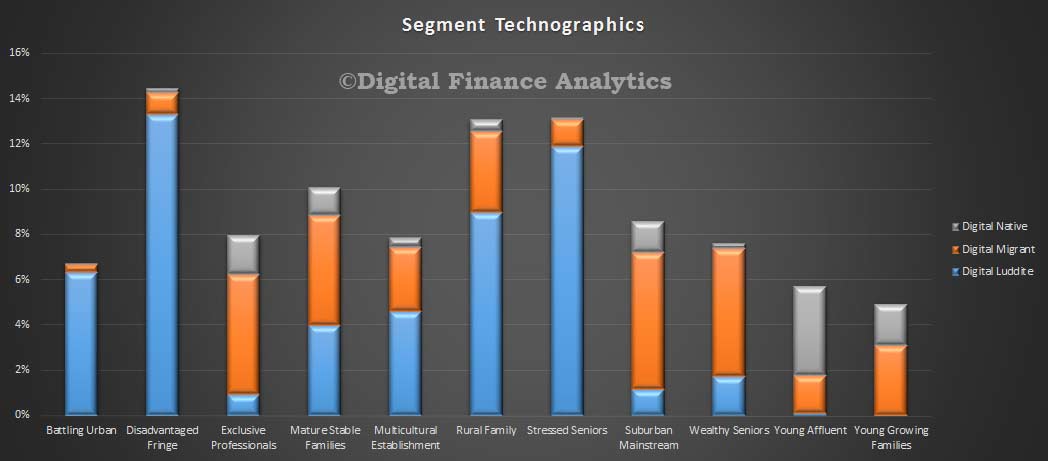

Next we looked at the technographic trends across our household segments using our digital segmentation, between those who are digital natives (always used digital), migrants (learning to use digital) and luddites (not willing or able to use digital). The chart below shows the relative distribution by segment across these three. The more affluent, and younger are most digitally aligned, and so are more likely to embrace Robo-Advice.

Next we looked at the technographic trends across our household segments using our digital segmentation, between those who are digital natives (always used digital), migrants (learning to use digital) and luddites (not willing or able to use digital). The chart below shows the relative distribution by segment across these three. The more affluent, and younger are most digitally aligned, and so are more likely to embrace Robo-Advice.

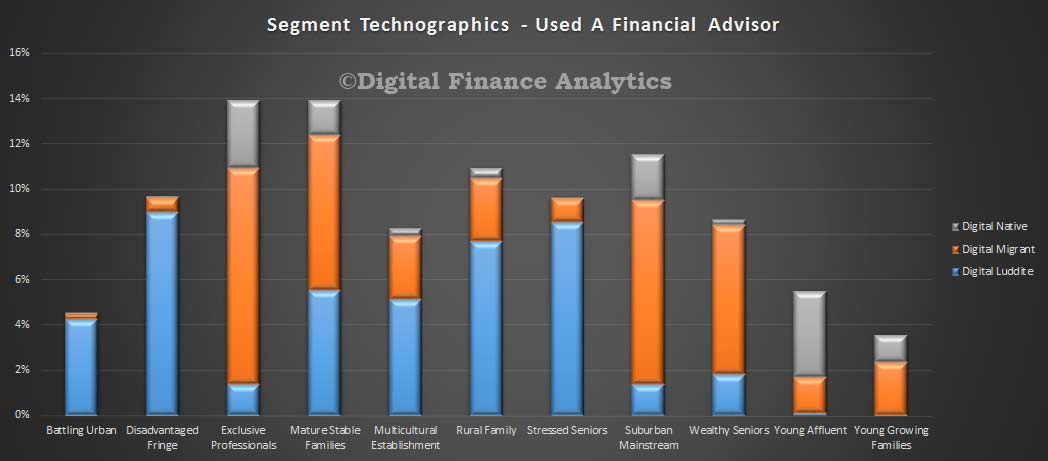

Next, we combine the data about getting financial advice and technographics. We find a greater proportion of households who are digitally aware have sought advice.

Next, we combine the data about getting financial advice and technographics. We find a greater proportion of households who are digitally aware have sought advice.

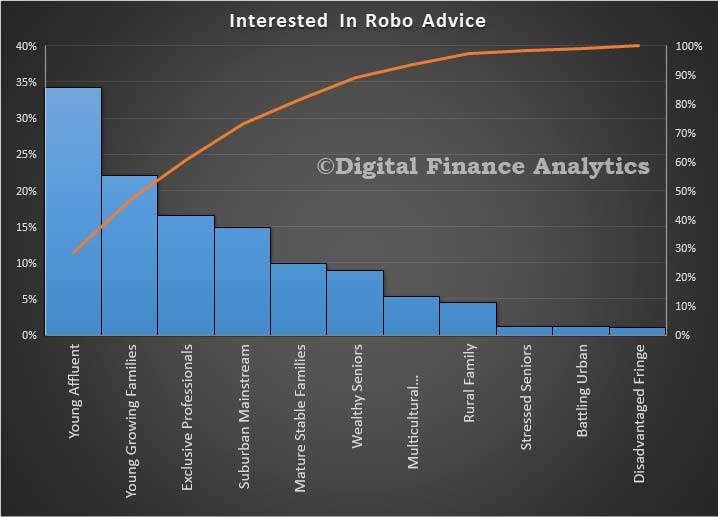

Finally, we asked in our surveys about households awareness and intention to consider Robo-Advice solutions if they were available. The results are shown below, with young affluent households, young growing families and exclusive professionals most likely to consider such a service. The proportions for each segment are those who would consider Robo-Advice, across all the digital segments.

Finally, we asked in our surveys about households awareness and intention to consider Robo-Advice solutions if they were available. The results are shown below, with young affluent households, young growing families and exclusive professionals most likely to consider such a service. The proportions for each segment are those who would consider Robo-Advice, across all the digital segments.

However, the analysis showed that those with existing advice relationships AND high digital alignment were most likely to consider Robo-Advice. Those who are digitally aligned, but not seeking advice showed no propensity to use such a service – at this point in time.

However, the analysis showed that those with existing advice relationships AND high digital alignment were most likely to consider Robo-Advice. Those who are digitally aligned, but not seeking advice showed no propensity to use such a service – at this point in time.

So two observations, first there are many different potential offerings which should be constructed on a Robo-Advice basis, as the needs, of young affluent, and very different from say exclusive professionals. So effective segmentation of the offers will be essential, and different personas will need to be incorporated into the systems being developed.

Second, the bulk of the interest lays with those who have had advice, so it may not, in the short term grow the advice pie. Indeed there appears to be strong evidence that existing advisors may find their business being cannabalised as existing clients switch to Robo-Advice. This is especially true if the range of options are greater, and the price point lower.

We therefore question the assumption expressed within the industry that Robo-Advice is not a threat, as it will simply expand the pie to segments which today do not seek advice. In fact, we suggest the clever play is to make it a tool, and aligned to Advisors, rather than a substitute for them. In addition, the marketing/education strategies need to be developed carefully. There is a lot in play here.