Glenn Stevens gave an address to the Economic Society of Australia in Brisbane where he discussed the need to align policy levers to drive growth and the limits of monetary policy.

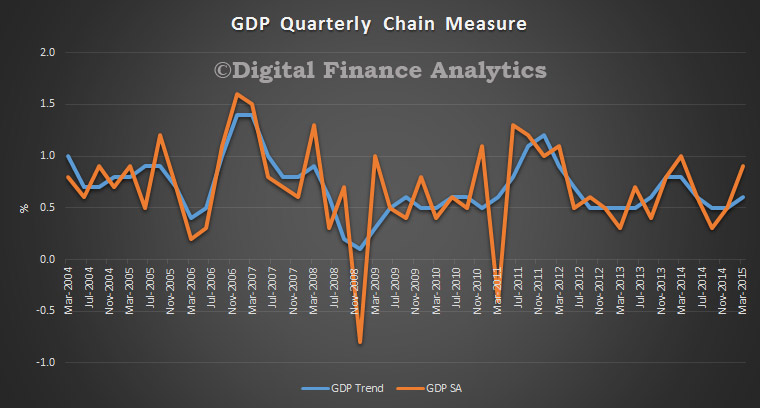

The latest edition of the Australian National Accounts, released last week, shows the picture. The quarterly growth figure was stronger than what had been embodied in our forecasts in the May Statement on Monetary Policy, though that comes after a weaker-than-expected outcome in the previous quarter. Some of the strength resulted from unusually high export shipments of resources, which were less disrupted by weather conditions in the ‘cyclone season’ than has often been the case in the past. Indications are that this pace of growth wasn’t repeated in the June quarter, when shipments of coal in particular were affected by weather disruptions on the east coast.

Taking the results over the past four quarters, growth was ‘below trend’. Export volume growth contributed strongly, while domestic final demand increased by a bit under 1 per cent, which is quite a weak result. Housing construction rose strongly, and consumer spending over the year rose by more than real household income (that is, the saving rate fell). Both these results owe a good deal to low interest rates and rising asset values.

But other components of demand were weak. Business investment fell substantially, with mining investment falling quickly and, as best we can tell, non-mining capital spending also weak. Public final spending didn’t grow at all. Public investment spending fell by 8 per cent over the past year.

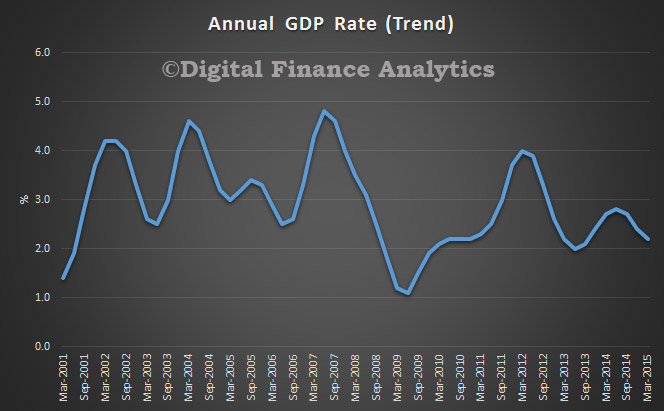

Overall, these outcomes are weaker that what, two years ago, we expected would be happening by now. Back then, the two-year-ahead forecast was for annual GDP growth to be in a range of 2½ to 4 per cent by mid 2015. The width of that range reflected the normal size of error margins, coupled with the inevitable uncertainty about the timing of when some components of demand outside of mining might strengthen, and the judgement that if accommodative monetary policy really was held in place for several years (which was a key assumption behind those forecasts), activity could at some point start to pick up quite quickly. It will be three months before we get the national accounts data for the June quarter, but at this point, with three of the four quarters available for the year to June 2015, it would appear that the outcome will be either right at the bottom of the range predicted two years ago or, more likely, a bit below it.

Of course, forecasts are hardly more than educated guesswork and two-year-ahead forecasts are even less reliable. That there are inevitably forecast errors is neither surprising nor new, and it is not any more concerning per se now than it always has been. This is far from the biggest forecast error I’ve seen over my three decades in this game.

But it is nonetheless useful to see what we can learn from those errors.

The following points are prominent:

- The terms of trade, which two years ago were assumed to fall, have in fact fallen further – they are about 12 per cent lower than the assumed path. That means national income is lower, which means spending power is lower.

- The exchange rate, which at that time was above parity against the US dollar, and was assumed to stay there, is now about 25 per cent lower. It has moved in the same direction as the terms of trade, which is normal.

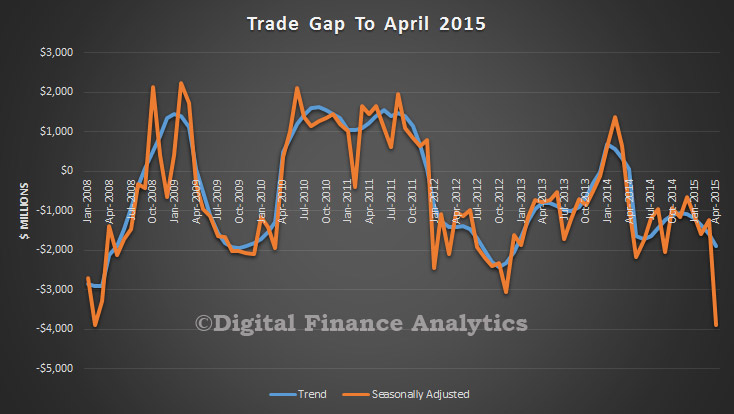

- The lower exchange rate has helped to produce a contribution to growth from ‘net exports’ much greater than earlier forecast, while that from domestic demand has been much weaker. The latter is mainly spread across non-mining business investment and weaker government spending, together with softer consumption on account of lower incomes. One thing which is not very different from the forecast from two years ago is that mining sector capital spending is falling sharply.

- Because the net effect of the above factors is that GDP growth has been on the weaker side of expectations, the unemployment rate is about half a percentage point higher than forecast two years ago. Consistent with that, growth in wages is, as you would expect, lower than forecast.

- Headline inflation is lower than forecast, largely because of the recent fall in oil prices. Underlying inflation is within the 2–3 per cent range that had been forecast. Again, the depreciation of the exchange rate has been a factor here.

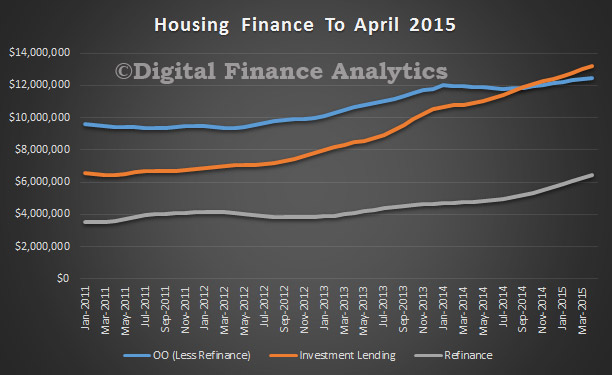

- The cash rate is 75 basis points lower than assumed two years ago, as monetary policy has used the room provided by contained inflation to try to do more to help growth. Lending rates have fallen on average by about 100 basis points over that period. This has produced a stronger result for housing construction than forecast and will also have contributed to the rise in dwelling prices.

In summary, the economy has in several important respects followed a different track from the one expected a couple of years ago. That is partly because conditions in the world economy were different from what had been expected and partly because several domestic factors were different.

Some in-built responses have been in evidence. For example the decline in the exchange rate, even if not by as much as we might have expected, has had the effect of supporting growth and keeping inflation from falling as much as it might have done. And, of course, monetary policy has also responded to the evolving situation, consistent with the Reserve Bank’s mandate. These responses have had the effect of lessening the extent to which growth and inflation have differed from the outcomes expected two years ago, but haven’t managed to eliminate those differences entirely, at least in the case of output growth.

The slowing in wage growth in response to soft labour market conditions has also undoubtedly helped to hold employment up. In fact wage growth appears to be somewhat lower than previous relationships between wages and unemployment would suggest. This may be a sign of increased price flexibility in the labour market and could help to explain why employment recently has looked a little higher relative to estimated GDP than might have been expected. These hypotheses can be advanced only tentatively, though, until we have more data.

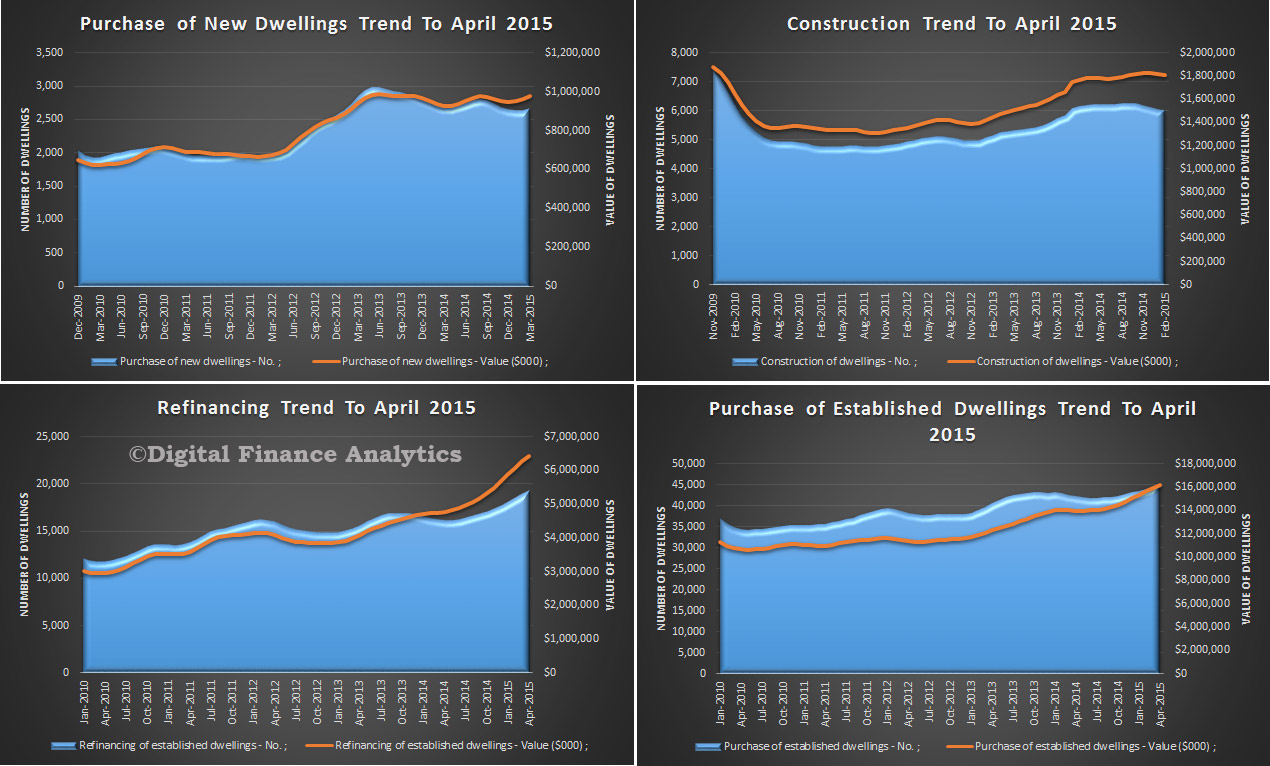

Looking ahead, the most recent forecasts suggest that growth rates will be similar to those we have observed recently for a while yet. Residential investment will reach new highs over the period ahead. Household consumption is expected to record moderate growth. With national income growth reduced by a falling terms of trade, this requires a modest decline in the saving rate. It doesn’t seem reasonable to expect much more from consumption growth than that.

Resources sector investment has a good deal further to fall yet over the next two years. Other areas of investment seem very low and while I would have expected that by now these would have been showing signs of strengthening, the most recent indications are for, if anything, a weakening over the year ahead. Public final spending has not been growing and fiscal consolidation still has some way to run. Under the current macroeconomic conditions, it would seem inappropriate for governments to seek additional restraint here in the near term.

Inflation is likely to remain low. Growth in labour costs is very low and some of the forces that were pushing up certain administered prices have started to reverse. So even if the exchange rate were to fall further, which in my view it needs to, we seem unlikely to have a problem with excessive inflation.

Putting all that together, as things stand, the economy could do with some more demand growth over the next couple of years.

Of course, these are forecasts. They might be wrong. In fact, they will be wrong, in some dimension or other. Our published material goes to some lengths to articulate a range of ‘risks’. It is easy to think of ‘downside’ ones in the current mood of determined pessimism.

But it is not entirely impossible to think of upside ones as well. A further fall in the exchange rate, which is not assumed in the forecasts, would add both to growth and prices. If one thinks that such a decline at some point is likely, that constitutes an ‘upside’ risk. Of course, the list of countries that would prefer a lower exchange rate is a long one and we can’t all have it.

That being so, we might give some thought to trying to create some upside risks to the growth outlook through policy initiatives. The Reserve Bank will remain attuned to what it can do, consistent with the various elements of its mandate – including price stability, full employment and financial stability. We remain open to the possibility of further policy easing, if that is, on balance, beneficial for sustainable growth.

The temptation, of course, is to presume outcomes can be fine-tuned by policy settings and that we can simply dial up more or less demand in short order to avoid deviations from some ideal path. Reality is inevitably more messy than that and has not always been kind to such fine-tuning notions. As it is, some observers think monetary policy has done too little, while others think it already has done way too much. I think it has been about right for the circumstances.

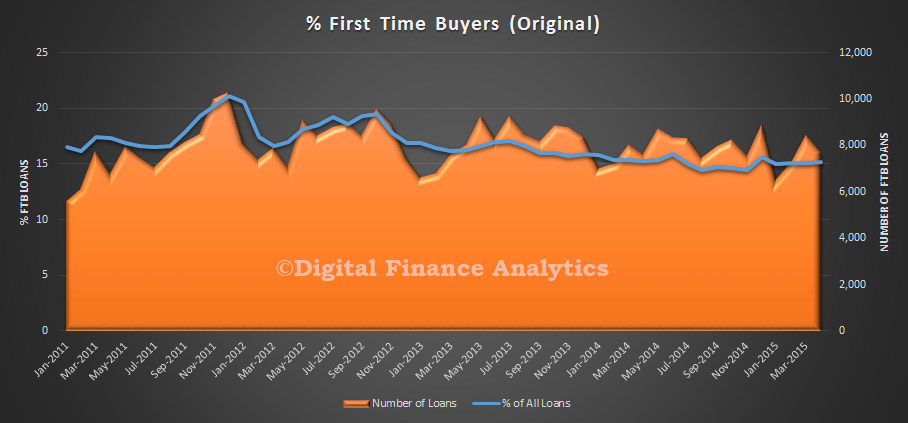

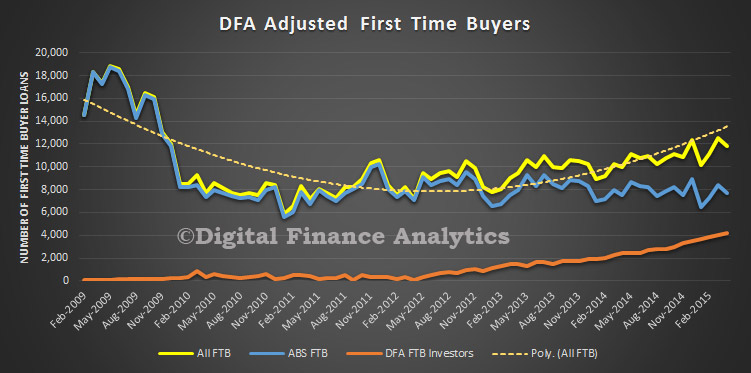

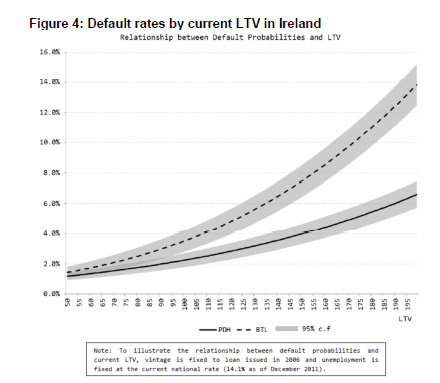

But the bigger point is that monetary policy alone can’t deliver everything we need and expecting too much from it can lead, in time, to much bigger problems. Much of the effect of monetary policy comes through the spending, borrowing and saving decisions of households. There isn’t much cause from research, or from current data, to expect a direct impact on business investment. But of all the three broad sectors – households, government and corporations – it is households that probably have the least scope to expand their balance sheets to drive spending. That’s because they already did that a decade or more ago. Their debt burden, while being well serviced and with low arrears rates, is already high. It is for this reason that I have previously noted some reservations about how much monetary policy can be expected to do to boost growth with lower and lower interest rates. It is not that monetary policy is entirely powerless, but its marginal effect may be smaller, and the associated risks greater, the lower interest rates go from already very low levels. I think everyone can see that.

If I am correct about this, it really is very important that other policies coalesce around a narrative for growth. In this regard, I think the Government is on the right track in not seeking to compensate for lower revenue growth by cutting spending further in the short run. Of course, some resolution of long-run budget trends is still going to be needed to sustain confidence and that will not be an easy conversation.

Meanwhile, as often remarked, infrastructure spending has a role to play in sustaining growth and also in generating confidence. I am doubtful of our capacity to deploy this sort of spending as a short-term countercyclical device. The evidence of history is that it takes too long to start and then too long to stop. But it would be confidence-enhancing if there was an agreed story about a long-term pipeline of infrastructure projects, surrounded by appropriate governance on project selection, risk-sharing between public and private sectors at varying stages of production and ownership, and appropriate pricing for use of the finished product. The suppliers would feel it was worth their while to improve their offering if projects were not just one-offs. The financial sector would be attracted to the opportunities for financing and asset ownership. The real economy would benefit from the steady pipeline of construction work – as opposed to a boom and bust. It would also benefit from confidence about improved efficiency of logistics over time resulting from the better infrastructure. Amenity would be improved for millions of ordinary citizens in their daily lives. We could unleash large potential benefits that at present are not available because of congestion in our transportation networks.

The impediments to this outcome are not financial. The funding would be available, with long term interest rates the lowest we have ever seen or are likely to. (And it is perfectly sensible for some public debt to be used to fund infrastructure that will earn a return. That is not the same as borrowing to pay pensions or public servants.) The impediments are in our decision-making processes and, it seems, in our inability to find political agreement on how to proceed.

Physical infrastructure is, of course, only part of what we need. The confidence-enhancing narrative needs to extend to skills, education, technology, the ability and freedom to respond to incentives, the ability to adapt and the willingness to take on risk. It is in these areas too, where there are various initiatives in place or planned, but which often do not get enough attention, that we need to create a positive dynamic of confidence, innovation and investment.

That is the upside we need to create.

The reason for this reversal can be explained with respect to a hypothetical $20,000 asset purchased on July 1, 2015, by a small incorporated entity. Under the proposed rules, the company would have reduced its tax payable by $5,700 in the first year, as compared to only $855 under the existing rules.

The reason for this reversal can be explained with respect to a hypothetical $20,000 asset purchased on July 1, 2015, by a small incorporated entity. Under the proposed rules, the company would have reduced its tax payable by $5,700 in the first year, as compared to only $855 under the existing rules.