We discuss a recent article on MMT.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/dec/08/turning-the-economic-tide-could-a-radical-monetary-theory-fix-australias-woes

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

We discuss a recent article on MMT.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/dec/08/turning-the-economic-tide-could-a-radical-monetary-theory-fix-australias-woes

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Contents 00:20 Introduction 00:48 US Markets 01:50 Labor Stats 05:20 Oil 06:00 Gold 06:45 Euro 07:00 China 08:00 UK 08:12 New Zealand 08:40 Bitcoin 11:55 Australian Section 11:55 Economic Data 13:00 Property – Opal Tower 14:00 Timber-PVC Cladding 15:40 PCI Index 16:20 Auctions 17:10 Prices 17:45 Council of Financial Regulators 20:00 Local Markets

I caught up with the founder of Hero Broker, Clint Howen to discuss what he is seeing in the mortgage industry at the moment. The online platform gives an interesting perspective on the changes in the market.

Global macroeconomic challenges are likely to increase pressure on the short-term earnings prospects of investment-grade banks in the Asia-Pacific, Fitch Ratings says in a new report. The report addresses the main questions asked by US and Canada-based investors during a recent tour by Fitch analysts to discuss mainly investment-grade rated banking systems, with particular focus on Australia, New Zealand, mainland China and Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Singapore.

Banks in most markets face several challenges to operating performance, including increased costs related to regulation, slower trade and economic growth, subdued loan growth, low interest rates and acute competition. These factors are squeezing net interest margins and overall profitability. However, while many banks are likely to report weaker financial results (or less improvement) in 2020 than in 2019, we do not expect significant deterioration, and there is unlikely to be any immediate impact on ratings. Consequently, the majority of bank ratings remain on Stable Outlook. Nevertheless, some banks in Australia (in particular, the major banks and their New Zealand subsidiaries) and in Japan are more exposed to negative rating pressure. Where this is the case, ratings are on Negative Outlook.

To combat these pressures, banks are increasingly competing for fee income as part of less asset-intensive (or risk-weighted asset-intensive) growth strategies, including boosting total income from key relationships. However, many banks have resorted to taking additional risk, typically credit risk, in search of greater revenue and margin drivers.

Increased risk appetite is appearing in various channels. These include expansion into banking systems in overseas markets where Fitch regards the operating environment as weaker; moving down the credit curve to support loan-yields (through SME lending and unsecured personal lending, for example); holding higher-yielding investment securities; and higher loan concentrations in certain sectors such as property. The latter has been attractive to banks from a risk-adjusted return perspective, but higher concentrations increase the risk of faster deterioration in less-benign operating conditions.

We expect Australia’s major banks to face further earnings pressure in 2020. Falling interest rates and slow credit growth are putting pressure on net interest income, while the sale of parts of the banks’ wealth management operations and a reduction in fees and commissions will hit non-interest income. We expect a modest uptick in impairment charges in the weaker operating environment, with households remaining susceptible to shocks in light of their high leverage, while remediation programmes and system investments will weigh on costs. Furthermore, higher prudential standards in Australia and New Zealand will weigh on overall returns on capital, even though they will support the intrinsic strength of the banks. Australia’s economy is stable but growth is subdued, with downside risk stemming mainly from a weaker global economy and the US-China trade dispute.

Bank ratings in China, Hong Kong, Korea and Singapore remain stable, reflecting either external support (sovereign or institutional) or the banks’ intrinsic financial profiles having adequate buffers at current rating levels to weather expected deterioration in 2020. Nevertheless, downside risks exist, due to external challenges and, in Hong Kong’s case, an economy hit hard by social unrest. Increasing exposure to faster-growing emerging markets is likely to add to pressure, but this may only become more evident when the operating environment is less benign. This is also the case for Japanese banks, and comes on top of structural challenges to their domestic operations, which are likely to continue dragging on earnings and internal capital generation.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand today released its final decisions following its comprehensive review of its capital framework for banks, known as the Capital Review. The trajectory will be over a longer period, with more flexibility, but the banks will still need to hold more capital.

Governor Adrian Orr said the decisions to increase capital requirements are about making the banking system safer for all New Zealanders, and will ensure bank owners have a meaningful stake in their businesses. The changes will be implemented over seven years, giving plenty of time for banks to manage a smooth transition and minimise any adjustment costs.

“Our decisions are not just about dollars and cents. More capital in the banking system better enables banks to weather economic volatility and maintain good, long-term, customer outcomes,” Mr Orr says.

“More capital also reduces the likelihood of a bank failure. Banking crises cause not only harmful economic costs but also distressful social issues, such as the general decline in mental and physical health brought about by higher rates of unemployment. These effects are felt for generations,” Mr Orr says.

The key decisions, which start to take effect from 1 July 2020, include banks’ total capital increasing from a minimum of 10.5% now, to 18% for the four large banks and 16% for the remaining smaller banks. The average level of capital currently held by banks is 14.1%.

Relative to the Reserve Bank’s initial proposals, the final decisions also include:

The adjustments to the original proposals reflect our analysis and industry feedback over the past two years. All of these changes will be phased in over a seven-year period, rather than over five years as originally proposed, in order to reduce the economic impacts of these changes.

Deputy Governor and General Manager of Financial Stability Geoff Bascand says the decisions were shaped by valuable public input and insight received through an unprecedented number of submissions as well as public focus groups. Three international experts also provided supportive perspectives on the proposals.

“We’ve listened to feedback and reviewed all the data, and are confident the decisions are the right ones for New Zealand,” Mr Bascand says.

“We have amended our original proposals in a number of ways so we achieve a high level of resilience at lower potential cost, with a smoother transition path for all participants. Our analysis shows that the benefits of these changes will greatly outweigh any potential costs.”

“Following the Global Financial Crisis, many regulators around the world have been taking steps to improve the safety of their banking systems. We’re confident we have the calibrations right for New Zealand conditions. These changes will be subject to monitoring, with the Reserve Bank reporting publicly on implementation during the transition period,” Mr Bascand says.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) has proposed substantially increasing the volume and breadth of data it makes publicly available on authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs), including banks, credit unions and building societies.

The move towards greater transparency and scrutiny of the banking sector is aimed at increasing accountability, supporting competition and lifting overall industry standards.

In a letter to industry today, APRA outlined plans to determine that all data collected for its quarterly ADI publications should be considered non-confidential, allowing it to be published. APRA currently publishes less than 1 per cent of the ADI data it collects due to legal restrictions contained within the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority Act 1998 (APRA Act). This change would allow APRA to significantly increase this figure.

From 2020, APRA proposes publishing:

The proposal supports

APRA’s strategic policy of increasing the transparency of data it collects, and

aligns with Government open data policies.

APRA’s Executive Director for Cross-Industry Insights and Data, Sean Carmody,

said: “APRA is committed to increasing transparency about the institutions and

industries we regulate.

“Under these proposed changes, APRA intends to publish – for the first time – a

range of information about individual ADIs, including their financial

performance and property exposures.

“As with the recent inclusion of data from credit unions and building societies

in our Monthly ADI Statistics publication, these changes are aimed at further

strengthening the ADI sector by enhancing accountability and encouraging

competition. They will also assist other regulatory agencies that rely on APRA

data, as well as analysts, policymakers and others who use our publications.”

Under the APRA Act, APRA must consult ADIs and their representatives, including

industry associations, before determining any new data to be non-confidential.

A 12 week consultation is now underway and concludes on 28 February 2020. APRA

is encouraging all interested parties to make submissions on issues including

what, if any, data should remain confidential.

APRA intends to consult on forms not included in this consultation at a later

date.

More details on the consultation, including the letter to industry, can be

found at: https://www.apra.gov.au/confidentiality-of-data-used-adi-quarterly-publications-and-additional-historical-data

The Reserve Bank will consider quantitative easing once rates fall to 25 basis points. It’s a tool that has been used by other countries, often with devastating consequences for society. Via InvestorDaily.

Australia is in uncharted territory, economically speaking. We’re latecomers to the low-rate party and we’re still getting used to it. Home owners are loving it but retailers are not. Unemployment is low but a record number of Aussies want to work more. It’s a strange time.

The Reserve Bank of Australia only has a few options left if it fails to hit its inflation target and lift economic growth. It can continue to reduce the cash rate and even go into negative rates, as the European Central Bank (ECB) had done. The ECB benchmark deposit rate was cut by 10 basis points in September to negative 0.5 per cent. The ECB also reintroduced its quantitative easing program of buying 20 billion euros ($32 billion) worth of government and corporate bonds every month in an effort to prevent the European economy from sliding off a cliff.

The ECB has been using QE on and off since 2009 in an effort to lift inflation. In 2015 the central bank began purchasing 60 billion euros worth of bonds each month. This increased to 80 billion euros in April 2016 before coming back down to 60 billion a year later.

In the UK, the Bank of England bought gilts (British government bonds) and corporate bonds during its QE program during the global financial crisis in 2009. QE programs also took place in 2011 and 2016.

Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve has undertaken three separate rounds of QE, the last of which it began tapering in June 2013. The US halted its program in October 2014 after acquiring a total US$4.5 trillion of assets.

When a QE program takes place, a central bank begins buying securities with money that didn’t exist before the QE process began. They are essentially printing money and giving it to large corporates and the government through the purchase of these bonds, the logic being that the proceeds will be used to buy new assets (like mortgages) and invest, which in turn will drive the economy.

The money doesn’t directly hit the wallets of consumers. Unlike “helicopter money”, which the Rudd government dished out during the financial crisis, QE has a much more indirect impact on consumers. Financially speaking.

But the broader political and social impacts have had a lasting psychological effect on the populations of Europe and the US.

“If we look at the experience offshore, QE has been great at raising the level of assets in conjunction with a permanently lower interest rate,” Fidelity International’s Anthony Doyle said this week.

“QE has stimulated asset price growth. The ‘haves’ have benefited compared to the ‘have nots’; income inequality has grown across the economies that have implemented quantitative easing and socially we have seen big shifts to the Right or to the Left in terms of the political spectrum.

“If you think about Donald Trump, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, Jeremy Corbyn, Brexit, Boris Johnson. The next decade could be characterised by moves to the Right or Left here as well if we follow a path that other economies have pursued.”

AMP Capital chief economist Shane Oliver told Investor Daily that QE “probably helps people who have shares and property more than it does people who have bank deposits.”

Prior to the election of Mr Trump in 2016, Luis Zingales of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business told Bloomberg that central bank policies are largely to blame for the rise of populism.

Here in Australia, the Reserve Bank will have to consider the impact that QE could have on a society that has witnessed a banking royal commission that exposed widespread misconduct within the financial services industry.

If the impact on Europe and the US of QE on the people is anything to go by, Australia is well placed to split down the middle and begin gathering on the far edges of the political spectrum.

We were late to the low rate party. We might just be late to the populism party too.

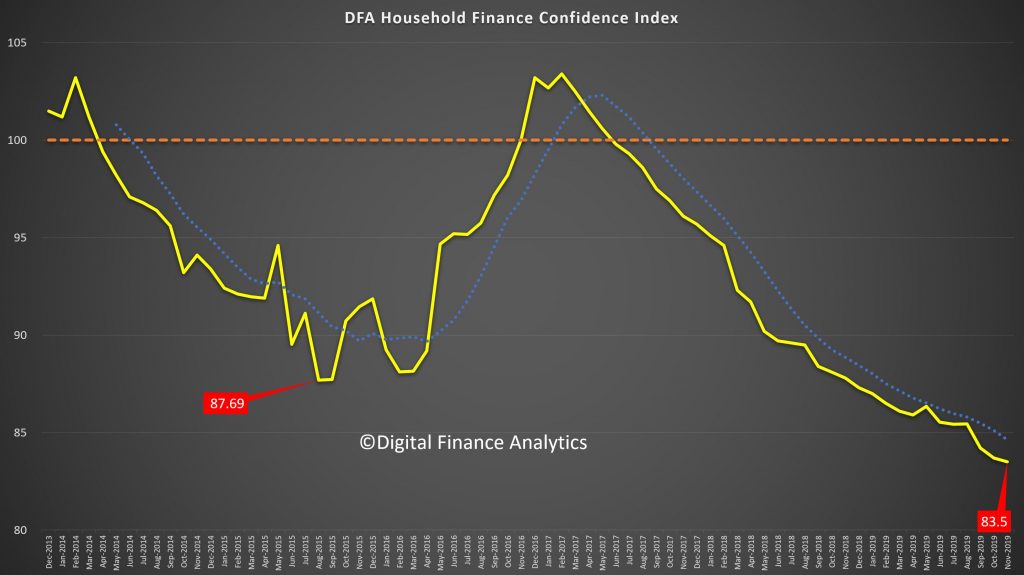

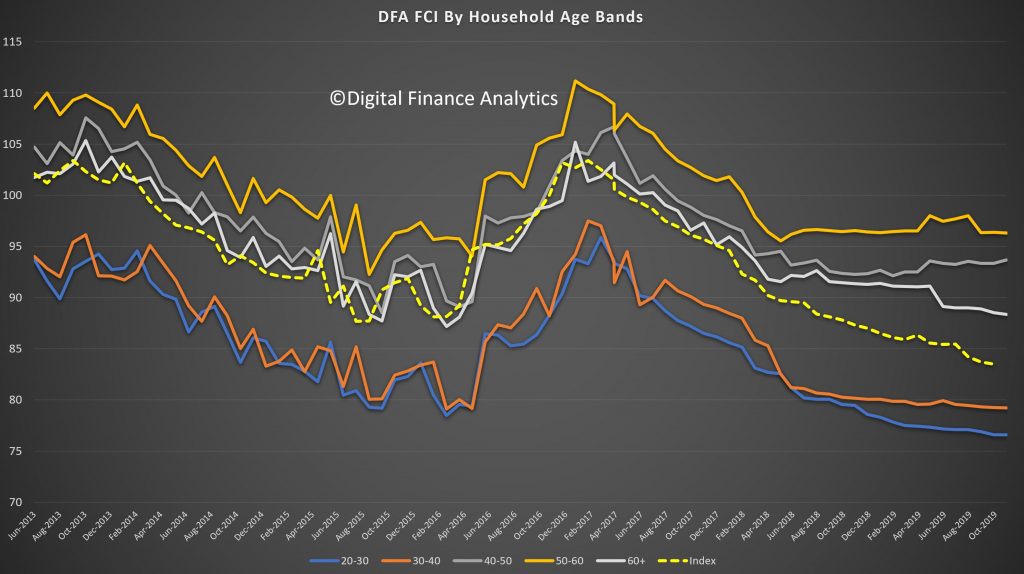

We continue to release the data from our household surveys to end November 2019. Today we look at our Household Financial Confidence Index, which examines how households are feeling about their financial status, relative to a year ago.

The index dropped again to 83.5, which is a new low in the series, and well below the previous 87.69 back in 2015. This level of concern suggests households will be keeping their wallets firmly in their pockets, so expect more retail weakness and household consumption easing lower ahead. The one “bright” spot was that more households are now believing their net worth is higher, thanks to the perceived recovery in home prices, and recent stock market highs, though offset by lower returns on deposits, flat incomes in real terms and rising costs. Recent rate cuts and tax refunds do not seem to have touched the sides!

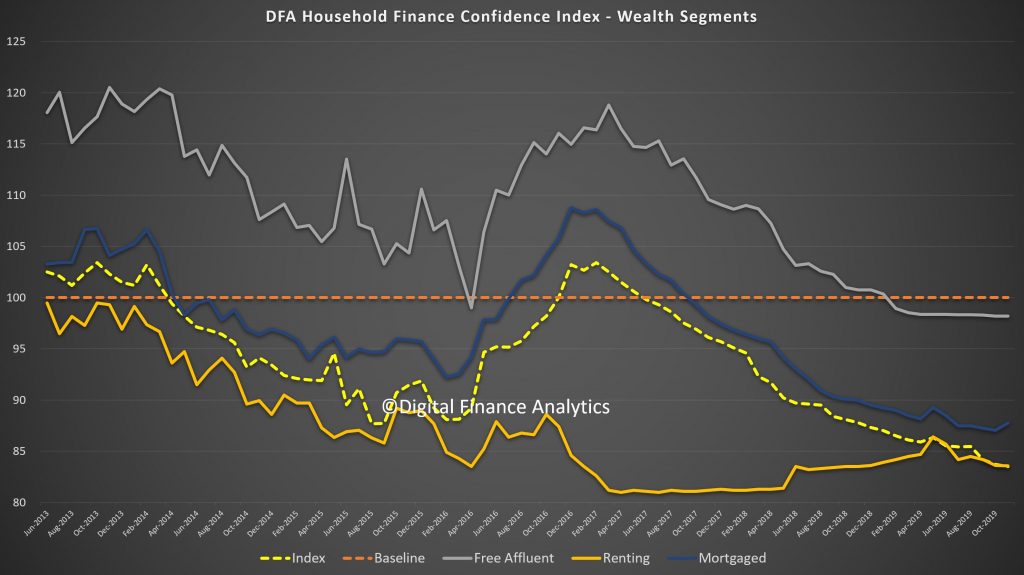

The declines in confidence are broad based, with those mortgage free still below neutral, while those with a mortgage still more negative, and those in the rental sector (without property) even more down than that.

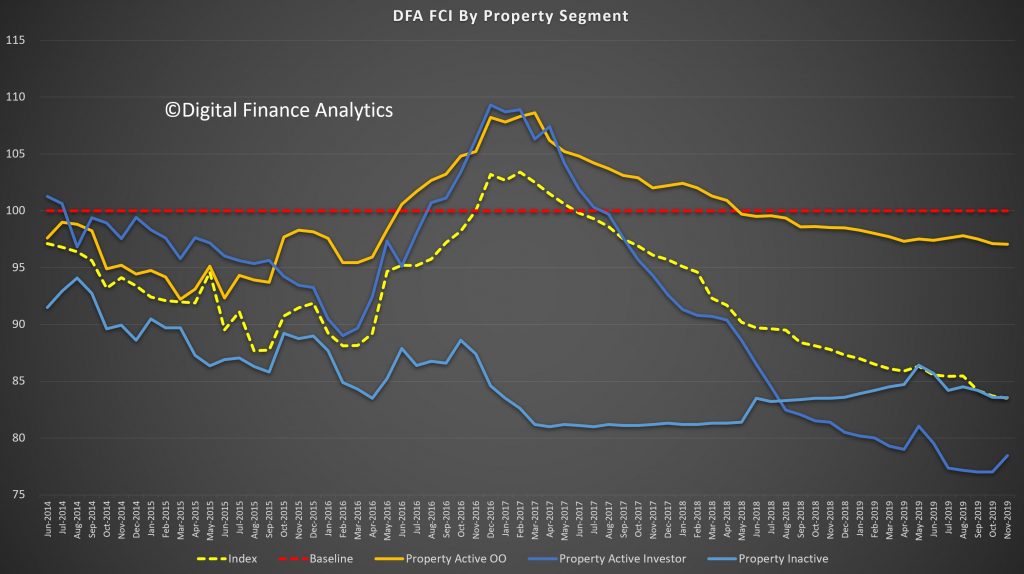

The news about rising home prices as impacted property investors, despite the continued weakness in rental income, thus we see a rise from very low levels for this cohort, from 77.01 to 78.45 in the month. On the other hand, property active owner occupied households were a little less positive, moving from 97.1 to 97.05. Property inactive households also drifted lower.

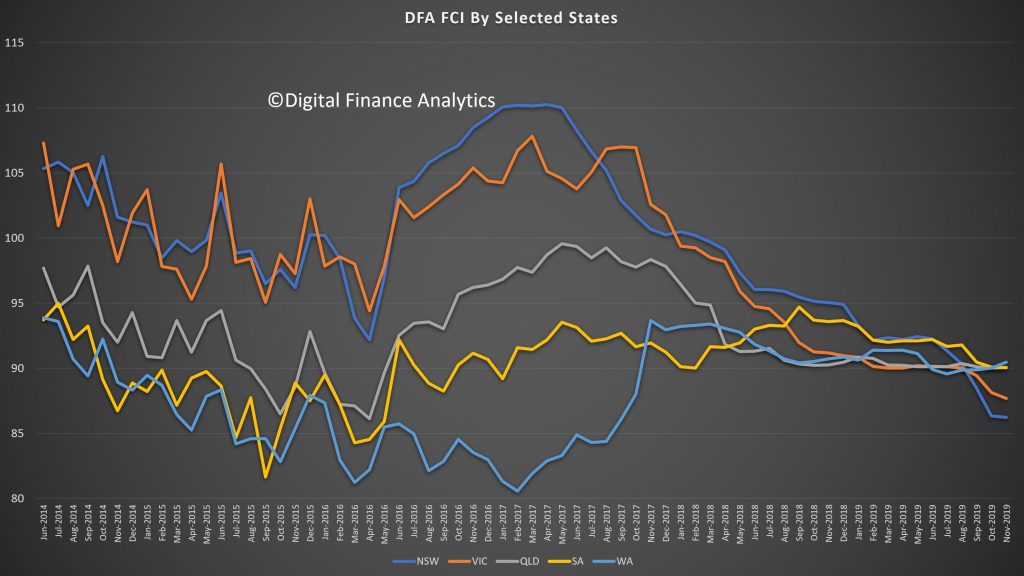

Across the states there was a significant decline in NSW, from 88.4 to 86.2, and this is connected with rising household budget pressures, and large mortgages in Sydney, plus the fires and drought across the state. VIC fell a little too, while there was a small rise in WA.

Across the age bands, those aged 20-30 reported the largest fall, thanks to pressure on incomes and rising costs. A number of new first time buyers who bought in recent months reside here. On the other hand, older cohorts are a little more positive this month, thanks to recent stock market rises, and some better home price news. We note, for example the headline of 6% plus rises in prices across Sydney have been interpreted by households in ALL post codes as appropriate to them – which shows the impact of a tricky headline, remembering that price rises are much higher in the more affluent upmarket postcodes.

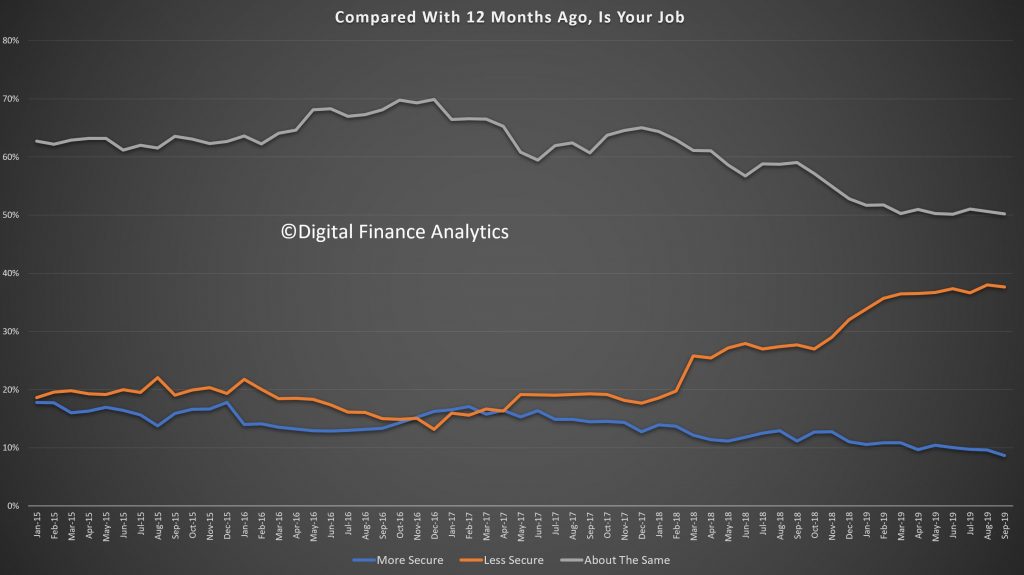

Turning to the moving parts within the index, job security is under pressure, thanks to underemployment, weakness in retail and construction, and the upcoming holidays. 7.8% felt more secure than a year ago, down from 8.23% last month. 38.65% said they were less secure compared with 38.12% last month.

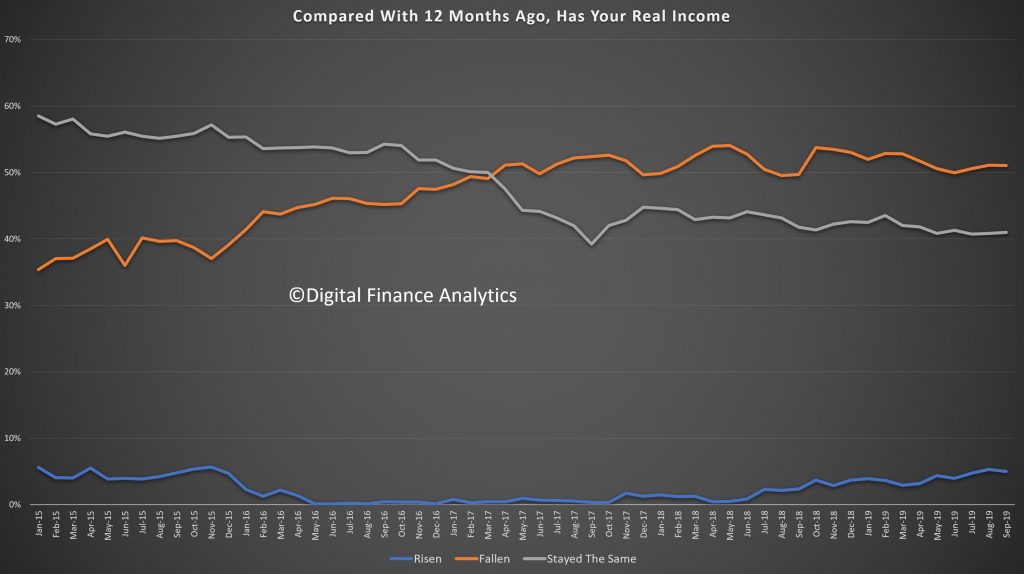

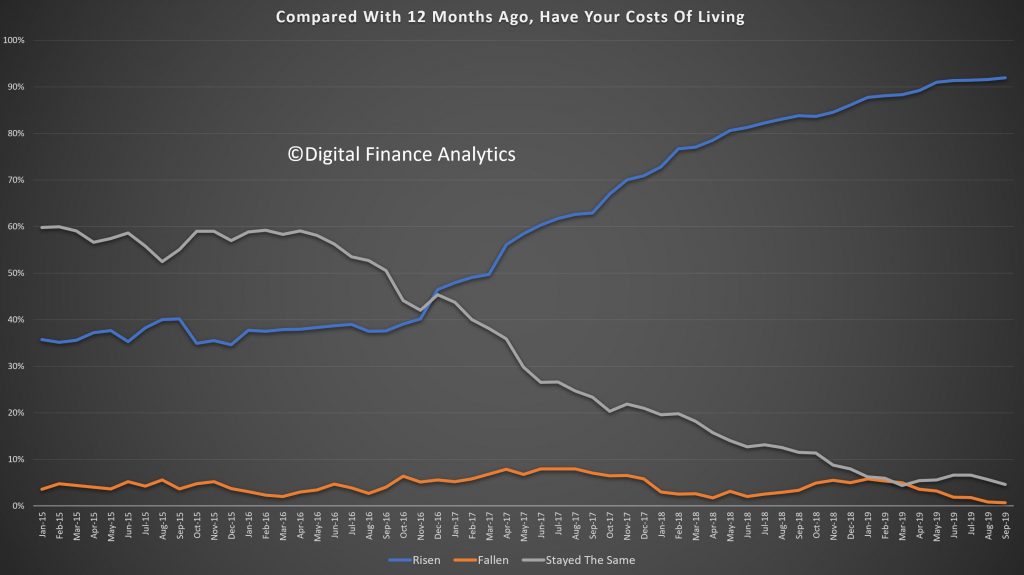

Incomes remain under pressure, with just 4.3% saying in real terms their incomes were higher than a year back, down from 5.3% last month. Pressure on household budgets is a pincer movement, as incomes are compressed (and returns from some investments and deposits fall). But costs of living are rising. In fact 94.2% reported higher costs than a year back, thanks to higher prices for fuel, electricity, school fees, childcare, and every needs. Only 1.3% said their costs of living had fallen.

Debt remains a major issue for many households, despite the rate cuts. Some households are paying down their mortgage faster than required, and are using the lower rates, and tax refunds for this. In an era of uncertainty, this is not a surprise. We also see a rise of households under pressure turning to payment options like AfterPay to support their purchases. Just 2% of households were more comfortable with their debt levels than a year ago, while 48% were less comfortable.

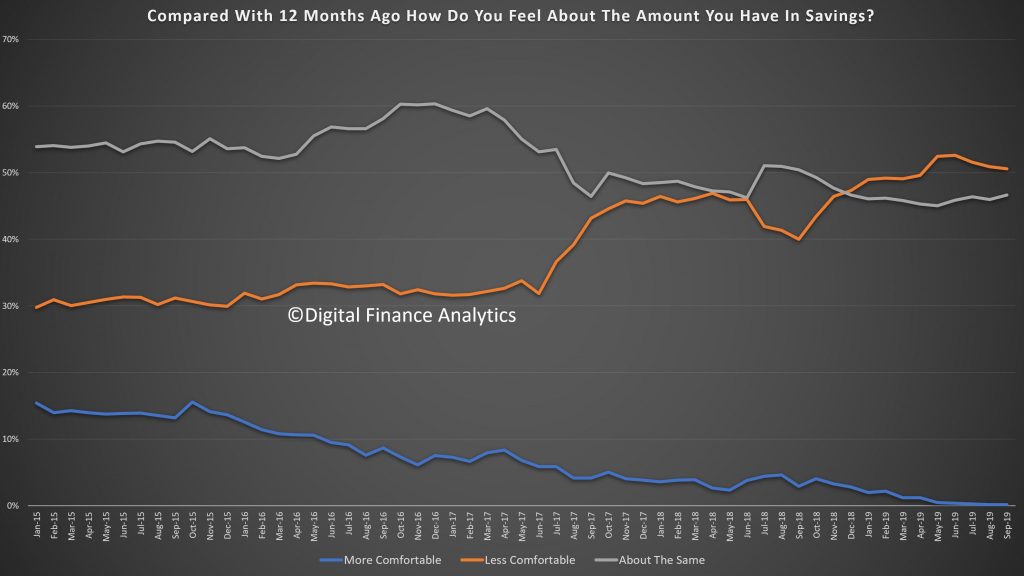

Some households have been building their savings (using lower mortgage rates and tax refunds) to build resilience for later. However, lower interest rates on deposits are creating its own pressures, while those with stocks and shares are seeing some dividend pressures too. Around 20% of households have insufficient funds to cover a month without work. Just 0.42% of households were more comfortable than a year ago, 49% were less comfortable and 45% about the same.

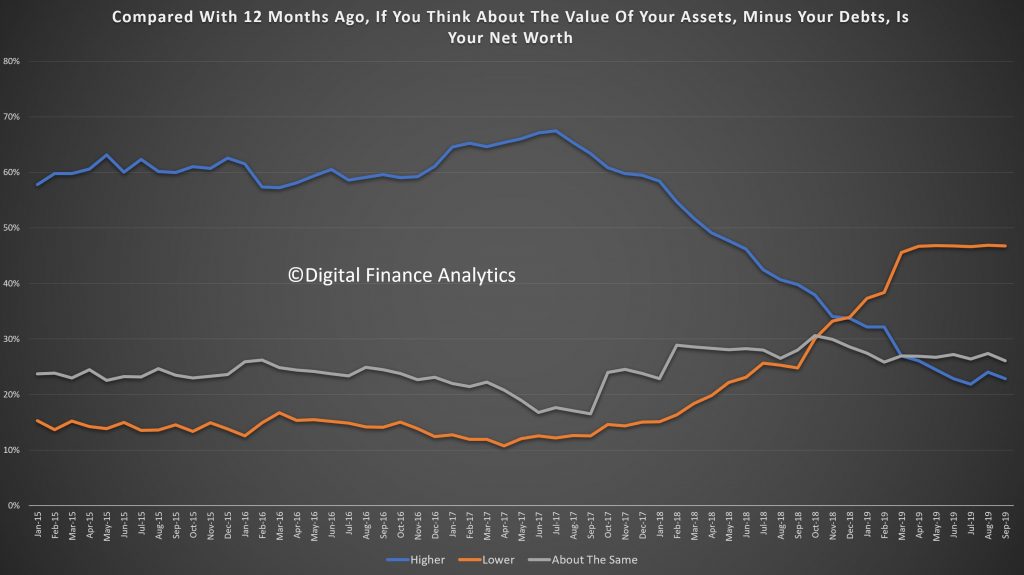

Finally, net worth – assets less liabilities, reacted to the higher reported home prices so that 27% say their net worth was better than a year ago up from 24% last month, while 43% were lower, and 24.65% about the same. Net worth was also boosted by high stock market prices and exchange rate movements.

So in conclusion, the household sector remains under pressure, and as a result financial confidence is bruised beyond immediate repair, that is until such time as wages growth really starts to accelerate in real terms. In addition the broader discussions about lower cash rates and quantitative easing are also helping to degrade confidence. The only bright spot, real or illusory, is the recovery in home prices (which are of course not uniform across the main centres and post codes). On this front, households are hoping for the best. We will see.

The Council of Financial Regulators (the Council) met on Friday, 29 November. The main topics discussed included the following:

The Australian Treasurer and representatives of the ACSC, AUSTRAC and the Department of Home Affairs attended for selected sessions.

Council of Financial Regulators

The Council of Financial Regulators (the Council) is the coordinating body for Australia’s main financial regulatory agencies. There are four members: the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), the Australian Treasury and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). The Reserve Bank Governor chairs the Council and the RBA provides secretariat support. It is a non-statutory body, without regulatory or policy decision-making powers. Those powers reside with its members. The Council’s objectives are to promote stability of the Australian financial system and support effective and efficient regulation by Australia’s financial regulatory agencies. In doing so, the Council recognises the benefits of a competitive, efficient and fair financial system. The Council operates as a forum for cooperation and coordination among member agencies. It meets each quarter, or more often if required.

Saxo Bank 2020 Outrageous Predictions:

Saxo Bank, a leading global multi-asset facilitator of capital markets products and services, has today released its 10 Outrageous Predictions for 2020. The predictions focus on a series of unlikely but underappreciated events which, if they were to occur, could send shockwaves across financial markets.

While these predictions do not constitute Saxo’s official market forecasts for 2020, they represent a warning of a potential misallocation of risk among investors who typically see just a one percent likelihood to these events materialising. It’s an exercise in considering the full extent of what is possible, even if not necessarily probable. Inevitably the outcomes that prove the most disruptive (and therefore outrageous) are those that are a surprise to consensus.

Commenting on this year’s Outrageous Predictions, Chief Economist at Saxo Bank, Steen Jakobsen said:

“This year’s Outrageous Predictions all play to the theme of disruption, because our current paradigm is simply at the end of the road. Not because we want it to end, but simply because extending the last decade’s trend into the future would mean a society at war with itself, markets replaced by governments, monopolies as the only business model and an utterly partisan and a highly fragmented and polarised public debate.

“It’s an environment where negative yields are now used to discriminate against access to mortgages for low income households, the elderly and students as regulatory capital requirement demands make credit hurdles too high for that group to get credit. Instead, they rent at twice the price of owning – a tax on the poor if ever there was one, and a driver of inequality. This, in turn, risks leaving an entire generation without the savings needed to own their own house, typically the only major asset that many medium and lower income households will ever obtain. Thus, we are denying the very economic mechanism that made the older generations ‘wealthy’ and risk driving a permanent generational wealth gap.

“We see 2020 as a year where at nearly every turn, disruption of the status quo is an overriding theme. The year could represent one big pendulum swing to opposites in politics, monetary and fiscal policy and, not least, the environment. In politics, this would mean the sudden failure of populism, replaced by commitments to “heal” instead of to divide. In policymaking, it could mean that central banks step aside and maybe even slightly normalise rates, while governments step into the breach with infrastructure and climate policy-linked spending.”

The Outrageous Predictions 2020 publication is available here with headline summaries below:

1. Australia’s nominal GDP to 8% on MMT

In 2020, economic red flags point to more downside ahead for the Australian economy. In Q1 of 2020, retail sales and cash register activity plunge to their lowest level since the 1991 recession and houses become more unaffordable, with Sydney and Melbourne being ranked among the world’s most expensive cities for housing. In Australia’s five biggest cities, more than 30% of average earnings are absorbed by mortgage repayments, leading to lower consumption and higher consumer stress.

The Australian economy could get a lift from the improving China credit impulse next year, but it is unlikely to be a game-changer as China’s credit transmission is still too slow. On the top of that, domestic monetary policy is also constrained as the effective zero-bound approaches and has limited positive effects on the real economy. RBA governor Philip Lowe was very vocal in 2019 on the limits of monetary policy and repeatedly explained that further rate cuts have only a marginal effect on GDP growth — arguing that fiscal stimulus is the only way to bring relief if the economy continues to weaken.

As consumer confidence and employment begin to plunge in early 2020, the government decides to embark on an MMT-inspired economic policy aimed at restoring confidence, stimulating GDP growth and attracting investment. This is the largest fiscal stimulus programme in Australia for at least 30 years. It leads to a massive increase in public spending in infrastructure, the health system and education, as well as the implementation of ambitious programmes to reduce the cost of living, provide affordable housing, reduce taxation and address environmental issues.

The strong rise in fiscal spending contributes to a jump in consumption and investment, almost doubling Australia’s nominal GDP rate to 8% in 2020. The business community applauds this bold new economic policy stance. Confidence and risk appetite are back. After being hit by a perfect storm that drove the Australian dollar down nearly 20% versus the greenback since early 2018, the AUD is among the best performing currencies in 2020.

2. The sudden arrival of stagflation rewards value over growth

The iShares MSCCI World Value Factor ETF leaves the FANGS in the dust, outperforming them by 25%.The world has now come full circle from the end of the Bretton Woods system, when it effectively shifted from a gold-based USD to a pure fiat USD system, with trillions of dollars borrowed into existence — not only in the US but all over the world. Each credit cycle has required ever lower rates and greater doses of stimulus to prevent a total seizure in the US and global financial system. With rates at their effective lower bound, and the US running enormous and growing deficits, the incoming US recession will require the Fed to super-size its balance sheet beyond imagination to finance massive new Trump fiscal outlays to bolster infrastructure in hopes of salvaging his election chances. But a strange thing happens: wages and prices rise sharply as the stimulus works its way through the economy, ironically due to the under-capacity in resources and skilled labour from prior lack of investment. Rising inflation and yields in turn spike the cost of capital, putting zombie companies out of business as weaker debtors scramble for funding. Globally, the USD suffers an intense devaluation as the market recognises that the Fed will only accelerate its balance sheet expansion while keeping its policy rate punitively low.

3. ECB folds and hikes rates

European banks on the comeback trail as the EuroStoxx bank index rises 30% in 2020.Despite the recent introduction of the tiering system, which has helped to mitigate the negative consequences of negative rates, banks are still facing a major crisis. They are confronted with a challenging economic and financial environment: marked by structurally ultra-low rates, an increase in regulation with Basel IV — which will further reduce the banks’ ROE — and competition from fintech companies in niche markets. In an unprecedented turn of events, in early January 2020, the new president of the ECB, Christine Lagarde — who has previously endorsed negative rates — executes a volte-face and declares that monetary policy has overreached its limits. She points out that maintaining negative deposit interest rates for a longer period could seriously harm the soundness of the European banking sector. In order to force euro area governments, and notably Germany, to step in and to use fiscal policy to stimulate the economy, the ECB reverses its monetary policy and hikes rates on January 23, 2020. This first hike is followed by another a short time later that quickly takes the policy rate back to zero and even slightly positive before year-end.

4. In energy, green is not the new black

The ratio of the VDE fossil fuel energy ETF to ICLN, a renewable energy ETF, jumps from 7 to 12. The oil and gas industry came roaring out of the financial crisis after 2009, returning some 131% from 2008 until the peak in June 2014 as China pulled the world economy out of its historic credit-led recession. Since then, the industry has been hurt by two powerful forces. The first was the advent of US shale gas and rapid strides in globalising natural gas supply chains via LNG. Then came the US shale oil revolution, which saw the US become the world’s largest oil and petroleum liquids producer. The second force has been the increasing political and popular capital behind fighting climate change, causing a massive surge in demand for renewable energy. The combined forces of lower prices and investors avoiding the black energy sector have pushed the equity valuation on traditional energy companies to a 23% discount to clean energy companies. In 2020, we see the tables turning for the investment outlook as OPEC extends production cuts, unprofitable US shale outfits slow output growth and demand rises from Asia once again.And not only will the oil and gas industry be a surprising winner in 2020 — the clean energy industry will simultaneously suffer a wake-up call.

5. South Africa electrocuted by ESKOM debt

USDZAR rises from 15 to 20 as the world cuts credit lines to South Africa. The very bad news is the South African government announcement late this year that in order to continue to bail out troubled utility ESKOM and keep the nation’s lights on, the budget next year is projected to balloon to its worst in over a decade at 6.5% of GDP, a sharp deterioration after the government managed to stabilise finances at a near constant -4% of GDP for the last few years. Worse still, the World Bank estimates that its external debt has more than doubled over that period to over 50% of GDP. The ESKOM fiasco may be the straw that will break the back of creditors’ willingness to continue funding a country that hasn’t had its financial or governance house in order for decades. Other uncreditworthy EMs will be drawn into the abyss as well in 2020, with the most differentiated performance across EM economies in years. The country teeters toward default.

6. US President Trump announces America First Tax to reduce trade deficit

A tax on all foreign-derived revenue scrambles supply lines and spikes inflation. US 10-year inflation-protected treasuries yield 6% in 2020 thanks to a rush of investor interest as the CPI rises. The year 2020 starts with reasonable stability on the trade policy front after the Trump administration and China manage at least a temporary détente on tariffs, currency policy and purchases of agricultural goods. But early in 2020 the US economy struggles for air and US trade deficits with China fail to materially improve, while Chinese purchases of agricultural products can’t realistically increase further. Eyeing polls showing a resounding defeat in the 2020 US Presidential election, Trump quickly grows restive and his administration drums up a new approach in a last-ditch effort to steal back the protectionist narrative: the America First Tax. Under the terms of this tax, the US corporate tax schedule is completely reconstructed to favour US-based production under the claimed principles of “fair and free trade”. The plan cancels all existing tariffs and instead slaps a flat value-added tax of 25% on all gross revenues in the US market that are sourced from foreign production. This brings stinging protests from trading partners for what are really just old tariffs in new clothes, but the administration counters that foreign companies are welcome to shift their production to the US to avoid the tax.

7. Sweden breaks bad

A massive and pragmatic attitude shift washes over Sweden as it gets to work to better integrate its immigrants and overstretched social services, driving a huge fiscal stimulus and steep rally in SEK. As often seems the case in Swedish policymaking, just as they took progressive taxation too far and collapsed the economy in the early 90’s, they have now taken political correctness on immigration so far that they have become politically incorrect. They are ignoring the large and growing contingent of Swedes who are questioning that policy, shutting them out of the debate. A parliamentary democracy should allow all groups of reasonable size a voice in the debate, but the traditional main parties of Sweden have taken the unusual collective decision to ignore the anti-immigration voice which has grown to represent more than 25% of the Swedish voters. The justification and intentions were good: openness and equality for all and safeguarding the Swedish open economic model. But anything taken too far can overwhelm, and to survive, all models need to be able to change when facts change. The other Nordic countries now talk of “Sweden conditions” as a threat, not as a model of best practice. Sweden is now in recession and with its small open economy status is extremely sensitive to the global slow down. This sense of crisis, social and economic, will create a mandate for change.

8. Democrats win a clean sweep in the US 2020 election, driven by women and millennials

The 2020 US election puts the Democrats in control of the presidency and both houses of Congress. Big healthcare and pharma stocks collapse 50%. The polls going into 2020 don’t look promising for Trump, and neither does the electorate. The marginal Trump voter in 2016 and in 2020 is old and white, a demographic that is fading in relative terms as the largest generation in the US now is the maturing millennial generation of 20-40-year-olds, a far more liberal demographic. Millennials and even the oldest of “generation Z” in the US have become intensely motivated by the injustices and inequality driven by central bank asset market pumping and fears of climate change, where President Trump is the ultimate lightning rod for rebellion as a climate change denier. The vote on the left is thoroughly rocked by dislike of Trump – with suburban women and millennials showing up to express their revulsion for Trump. The Democrats win the popular vote by over 20 million, grow their control of the House, and even narrowly take the Senate. Medicare for all and negotiations for drug pricing bring a massive haircut to the industry’s profitability.

9. Hungary leaves the EU

Hungary has been an impressive economic success since it joined the EU in 2004. But the 15-year marriage now seems in trouble after the EU initiated an Article 7 procedure against the country, citing Hungary’s – or really PM Orbán’s — ever-tighter restrictions on free media, judges, academics, minorities and rights groups. The push back from Hungary’s leadership is that the country is only protecting itself: mainly protecting its culture from mass immigration. It’s an unsustainable status quo, and the two sides will find it tough to reconcile in 2020 as the Article 7 procedure moves slowly through the EU system. PM Orbán is even openly talking about how Hungary is a ‘blood brother’ with the renegade Turkey as opposed to a part of the rest of Europe, a big shift in rhetoric, a change of tone which coincides with EU transfers all but disappearing over the next two years. Hungary’s currency, the forint (HUF) is on the back foot and reaches a much weaker level of 375 in EURHUF terms as the markets fear the disengagement or reversal of capital flows as EU companies reconsidered their investment in Hungary.

10. Asia launches new reserve currency in move away from US dollar dependence An Asian, AIIB-backed digital reserve currency takes the US dollar index down by 20% and tanks the US dollar 30% versus gold. To confront a deepening trade rivalry and vulnerabilities from rising US threats to weaponise the US dollar and its control of global finances, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank creates a new reserve asset called the Asian Drawing Right, or ADR, with 1 ADR equivalent to 2 US dollars, making the ADR the world’s largest currency unit. The move is clearly aimed at de-dollarising regional trade. Local economies multilaterally agree to begin conducting all trade in the region in ADRs only, with major oil exporters Russia and the OPEC nations happy to sign up due to their growing reliance on the Asian market. The redenomination of a sizable chunk of global trade away from the US dollar leaves the US ever shorter of the inflows needed to fund its twin deficits. The USD weakens 20% versus the ADR within months and 30% against gold, taking spot gold well beyond USD 2000 per ounce in 2020.