The Treasurer has released for public consultation the Government’s response to the Senate Economics References Committee Inquiry into matters relating to credit card interest rates. The Government’s response outlines reforms to provide greater legislative protection to vulnerable consumers, to exert more competitive pressure on credit card issuers and to provide consumers with the information they need to make the best choices about how they use their credit cards.

Background.

There are currently around 16 million credit and charge card accounts in Australia (or 1.8 cards per household). Around two-thirds of outstanding credit card debt (by value) is accruing interest. This proportion has fallen over recent years (from above 70 per cent in 2011). The decline likely reflects that credit cards are an expensive form of credit and their relative price has increased in recent years as interest rates on other forms of credit — such as household mortgages and personal loans — have fallen. Increasing use of debit cards, and the growing availability of discounted balance transfer offers, may also have been important, whilst reforms enacted under the National Consumer Credit Protection Act in 2009 and 2011 may have contributed to improved repayment behaviour.

Available data indicate that the debt-servicing burden associated with outstanding credit card balances falls more heavily on households with relatively low levels of income and wealth. Households in the lowest income quintile hold, on average, credit card debt equal to 4 per cent of their annual disposable income, while those in the highest income quintile hold debt equal to around 2 per cent of disposable income. Low income households are also more likely to persistently revolve credit card balances (and, therefore, pay interest) than high income households.

The ABS’ Household Income and Expenditure surveys show that households in the lowest income quintiles also pay more in interest charges relative to their incomes than higher income households, although overall differences between quintiles are small. Households in the bottom two quintiles by net worth also pay the most in credit card interest relative to their income.

Although reliable data on the number of consumers that are in credit card distress are not publically available, a range of evidence supports the conclusion that carrying large credit card debt is a significant cause of financial vulnerability and distress for a small but sizeable subset of consumers.

Default rates on credit cards give a sense of the proportion of credit card balances that are in severe distress. Recent estimates from the RBA suggest that total (annualised) losses on the major banks’ credit card loan portfolios are around 2½ per cent.5 Other data suggest that many consumers struggle to make the required repayments on credit cards without necessarily defaulting. A 2010 survey by Citi Australia found that 9 per cent of respondents reported that they had struggled to make minimum repayments on credit cards within the past 12 months, with low-income earners being more likely to report this than high-income earners.

Compared to other types of loans, the number of consumers struggling to or failing to make the required repayment is likely to understate the financial distress associated with credit cards. Card issuers set minimum repayment amounts as a very small proportion of the outstanding balance, so that households making the minimum repayment will only pay off their balance over a very long period and incur very large interest costs. Making the higher repayments required to pay off their outstanding balance may be sufficient to cause financial distress for many consumers.

In giving evidence to the Senate’s inquiry into the issue, the Consumer Action Law Centre (Consumer Action) and the Financial Rights Legal Centre (Financial Rights) stated that credit card debt is the most commonly cited problem by callers to Financial Rights’ financial counselling telephone service. Consistent with this, Consumer Action’s telephone service is reported to receive at least 15 calls per day related to credit card debt, with over 50 per cent of callers having credit card debt exceeding $10,000 and 28 per cent with a debt of over $28,000. Credit cards are also the most common cause of consumer credit disputes received by the Financial Ombudsman Service — of the more than 11,000 consumer credit disputes received in 2014-15, almost half were about credit cards. In contrast to the number of home loan disputes, which fell by 5 per cent over 2014-15, the number of credit card disputes rose by almost 4 per cent.

Apart from its direct financial impact, high and unmanageable credit card debt can have a significant impact on other indicators of wellbeing. An examination of financial stress amongst New South Wales households by Wesley Mission detailed the impact that financial stress can have on the household and individual, including impacts on physical and mental health, family wellbeing, interfamily relationships, social engagement and community participation. More than one quarter of respondents that identified themselves as having been in financial stress indicated that the experience had resulted in sickness or physical illness (31 per cent), relationship issues (28 per cent) or a diagnosed mental illness (28 per cent). While there are many causes of financial stress, Wesley Mission found that financially stressed households owed, on average, 70 per cent more in credit card debt than households that weren’t financially stressed.

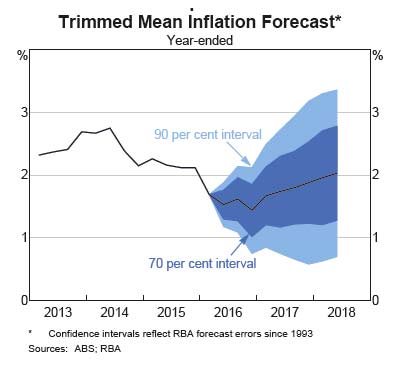

In addition, the inflexibility of credit card interest rates to successive reductions in the official cash rate has prompted concern over the level of competition in the credit card market. Since late 2011, the average interest rate on ‘standard’ credit cards monitored by the RBA has remained around 20 per cent, at a time when the official cash rate has been reduced by a cumulative 2.75 percentage points. The average rate on ‘low rate’ cards (around 13 per cent) has been similarly unresponsive to reductions in the cash rate over the period.

Analysis conducted by the Treasury in 2015 showed that effective spreads earned by credit card providers have increased over the past decade. In particular, spreads increased substantially during the financial crisis and have remained high in the years since then.11 The increase during the financial crisis is consistent with a repricing of unsecured credit risk observed in other credit markets and economies. However, the fact that spreads have since remained very high (and have even increased a little further more recently) suggests limitations in the degree of competition in the credit card market and unsecured lending markets more generally.

Proposals For Consultation.

Credit cards are used by many Australians as a valuable tool for managing their financial affairs. The majority of Australians use their credit cards responsibly. There is, however, a subset of consumers incurring very high credit card interest charges on a persistent basis because of the inappropriate selection and provision of credit cards as well as certain patterns of credit card use. For this subset of consumers, credit cards may impose a substantial burden on financial wellbeing.

The Government finds that these outcomes reflect, among other things, a relative lack of competition on ongoing interest rates in the credit card market (arising partly because of the complexity with which interest is calculated). These outcomes also reflect behavioural biases that encourage card holders to borrow more and repay less than they would otherwise intend leading to higher (than intended) levels of credit card debt.

These views are consistent with the findings of the recent Inquiry into matters relating to credit card interest rates by the Senate Economics References Committee released in December 2015. On 18 December 2015, the Senate Committee released its report entitled Interest Rates and Informed Choice in the Australian Credit Card Market. The Government has carefully considered the recommendations made by the Senate Committee. This consultation paper also constitutes the Government’s response to that Inquiry.

The Government proposes a set of reforms that it considers are proportionate to the magnitude of the identified problems. It has drawn upon lessons and insights from regulatory developments in other jurisdictions as well as available empirical evidence, including relevant insights from behavioural economics. The Government has further drawn on evidence given by stakeholders at the Senate Inquiry hearings and its own consultation with card issuers and consumer representatives.

The proposed measures form part of a wider package of reforms that should improve competition and consumer outcomes in the credit card market. A number of aspects of the Financial System Program announced by the Government in October 2015 — including measures to improve the efficiency of the payments system and support access to and sharing of credit data — should also have a material and positive impact on consumer outcomes in the credit card market. There are already signs that reforms enacted in January 2015 to open up the credit card market to a wider pool of potential card issuers are beginning to have a positive impact on competition in the market.

Relatedly, on 19 April 2016 the Government released the final report of the review of the small amount credit contract (SACC) laws. Consistent with its approach to the credit card market, the Government wants to ensure that the SACC regulatory framework balances protecting vulnerable consumers without imposing an undue regulatory burden on industry. The final report made recommendations to increase financial inclusion and reduce the risk that consumers may be unable to meet their basic needs or may default on other necessary commitments. The Government is undertaking further consultation before making any decisions on the recommendations.

The Government recognises the importance of financial literacy in supporting good consumer outcomes in the financial system and is committed to raising the standard of financial literacy across the community. The Government provides funding to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to lead the National Financial Literacy Strategy and undertake a number of initiatives to bolster financial literacy under the ASIC MoneySmart program.

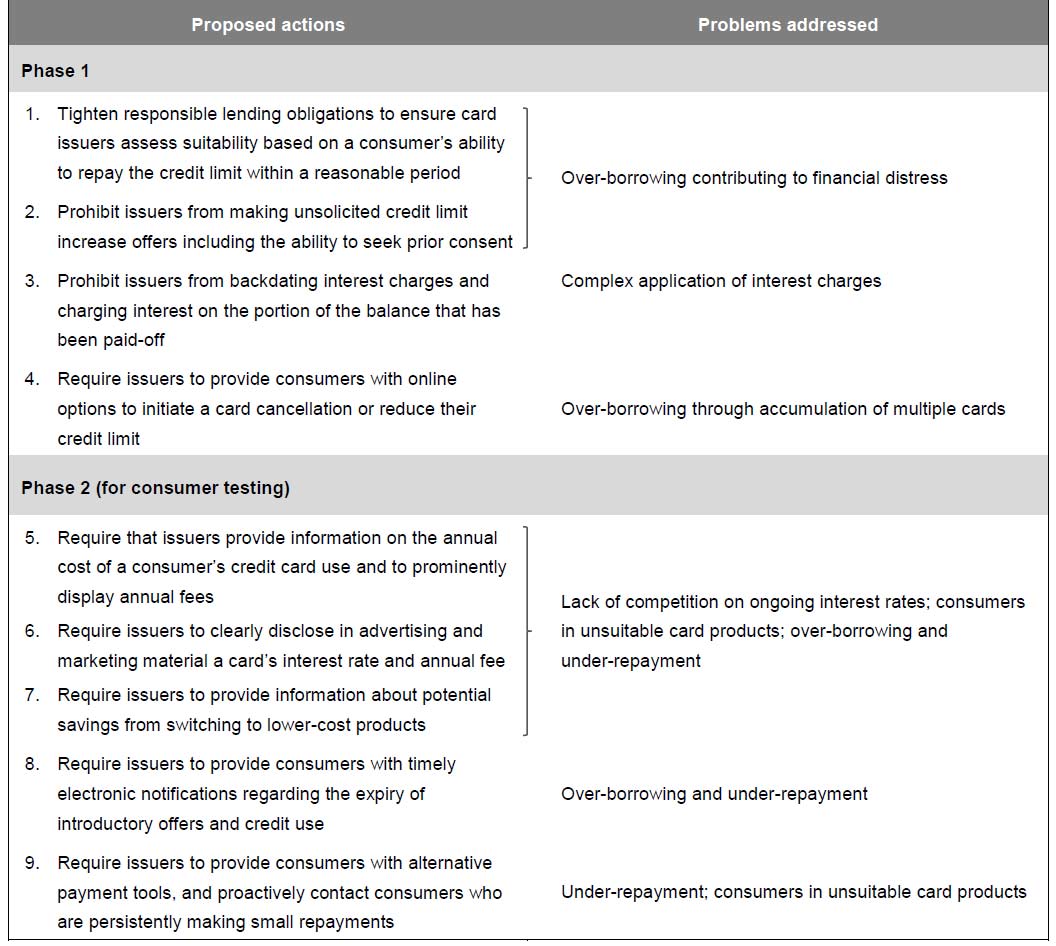

The package consists of two phases. For Phase 1 (measures 1 to 4), the Government seeks stakeholder feedback with a view to developing and releasing associated exposure draft legislation in the near term. For Phase 2 (measures 5 to 9), the Government plans to shortly commence behavioural testing with consumers to determine efficacy in the Australian market and to ensure they are designed for maximum effect. Testing will be led by the Behavioural Economics Team of the Australian Government. The decision to implement these measures will be subject to the results of consumer testing and the extent to which industry presents solutions of its own accord. The Government intends to commence consumer testing in the near term and will report on the outcomes of that testing and make a final decision on implementation in due course.