The IMF released their latest review of Australia. They expect growth to remain under trend to 2.8% in 2020, house prices to remain high along with household debt, household savings to fall, and the cash rate to fall before rising later. Mining investment will continue to fall, and non mining investment to rise, with a slow fall in unemployment to 5.5% by 2020. They supported the FSI recommendations for banks to hold more capital. They cautioned that if investor lending and house price inflation do not slow appreciably, these policies may need to be intensified.

On September 14, the Executive Board of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) concluded the 2015 Article IV consultation1 with Australia.

Australia has enjoyed exceptionally strong income growth for the past two decades, supported by the boom in global demand for Australia’s natural resources and strong policy frameworks. However, the economy is now facing a large transition as the mining investment boom winds down and the terms of trade has fallen back. Growth has been below trend for two years. Annualized GDP growth was around 2.2 percent in the first half of 2015, with particularly weak final domestic demand, and declining public and private investment. Capacity utilization and a soft labor market point to a sizeable output gap. Nominal wage growth is weak, contributing to low inflation.

The terms of trade has fallen sharply over the past year. Iron ore prices have fallen by more than a third and Australia’s commodities prices are down by around a quarter since mid-2014. The exchange rate has depreciated further in recent months following news about economic and financial market developments in China. This has significantly reduced the likely degree of exchange rate overvaluation and should help support activity. Although the current account deficit narrowed to 2.8 percent of GDP in 2014 as mining-related imports declined, it is expected to widen somewhat in 2015.

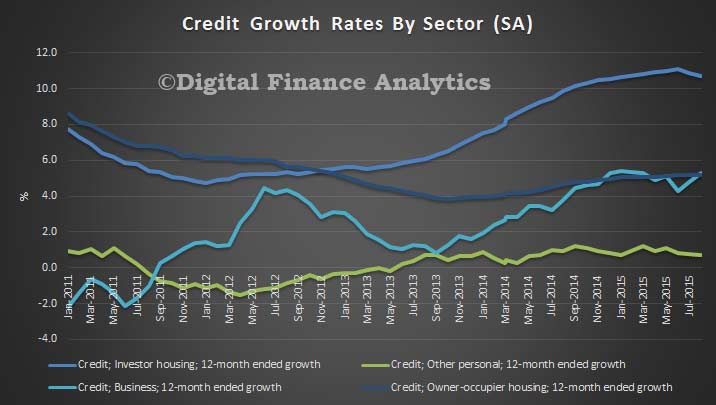

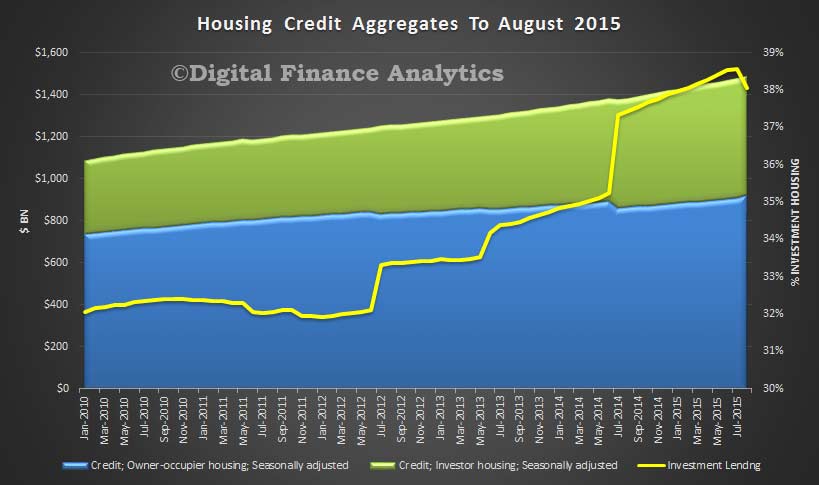

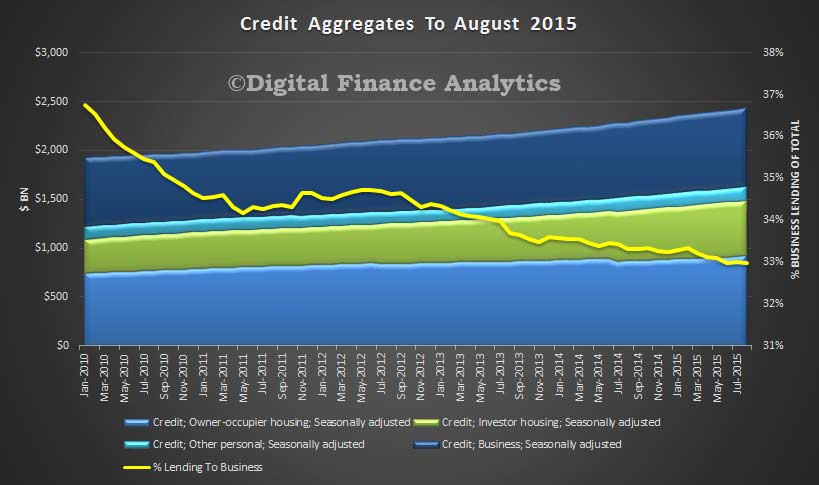

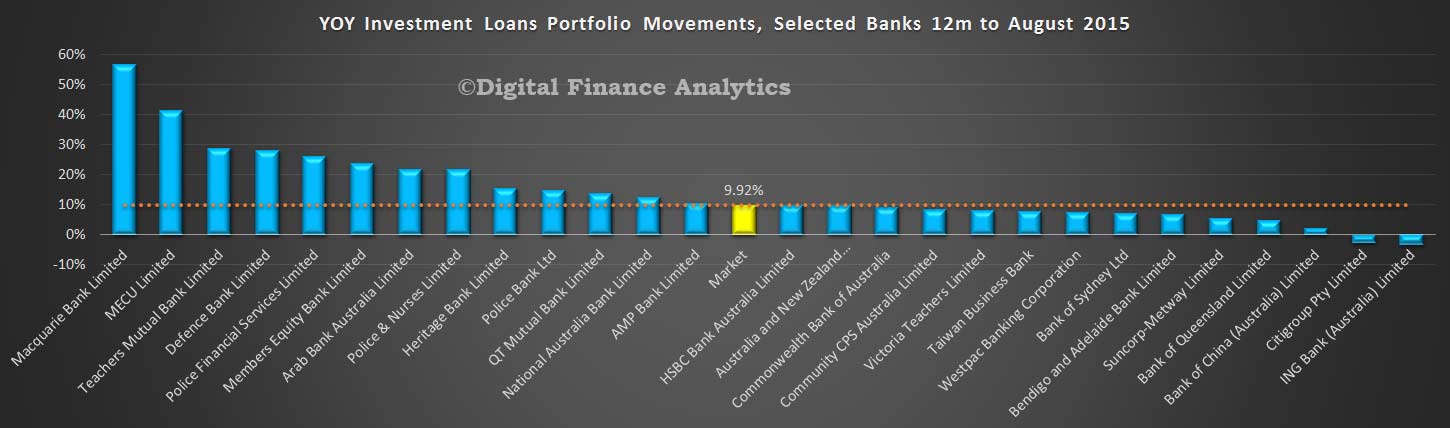

With subdued inflation pressure, and a weaker outlook, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut its policy rate by a further 50bps in the first half of 2015 to 2 percent. While housing investment has picked up strongly, consumer confidence indicators and investment expectations remain muted. Consumption growth has also been moderate reflecting weak income growth. But low interest rates have pushed up asset prices. Overall house price inflation is close to 10 percent, but is around 18 percent in Sydney. Buoyant housing investor lending has recently prompted regulatory action to reinforce sound residential mortgage lending practices.

Fiscal consolidation has become more difficult and public debt is rising, albeit from a low level. Lower export prices and weak wage growth are denting nominal tax revenues; unemployment is adding to expenditures. The national fiscal deficit remained at 3 percent in fiscal year

(FY, July–June) 2014/15, broadly unchanged from the previous year. The FY 2015/16 Budget projects a return to surplus in 2019–20. The combination of tightening by the States and the commonwealth implies an improvement in the national cyclically-adjusted balance by some 0.7 of a percent of GDP on average over the next three years.

Executive Directors commended Australia’s strong economic performance over the past two decades, which has been underpinned by sound policies, the flexible exchange rate regime, earlier structural reforms, and a boom in the global demand for resources. They noted, however, that declining investment in mining and a sharp fall in the terms of trade are posing macroeconomic challenges, while potential growth is likely to slow in the period ahead. Accordingly, Directors agreed that continued efforts to support aggregate demand and raise productivity will be critical in transitioning to a broader-based and high growth path.

Directors noted that a supportive policy mix is needed to facilitate the structural changes underway. With a still sizeable output gap and subdued inflation, most Directors agreed that monetary policy is appropriately accommodative and could be eased further if the cyclical rebound disappoints, provided financial risks remain contained. Directors also noted that the floating exchange rate provides an important buffer for the economy.

Directors broadly agreed that a small surplus should remain a longer-term anchor of fiscal policy. In this regard, many Directors supported the authorities’ planned pace of adjustment, which they viewed as striking the right balance between supporting near-term activity and addressing longer-term spending commitments. Some Directors, however, considered that consolidation could be somewhat less frontloaded, given ample fiscal space. Directors broadly concurred that boosting public investment would support demand, take pressure off monetary policy, and insure against downside risks. In this context, they welcomed the authorities’ continuing to establish a pipeline of high-quality projects.

Directors highlighted that maintaining income growth at past rates and boosting potential growth would require higher productivity growth. They expressed confidence that this could be achieved, given Australia’s strong institutions, flexible economy, track record of undertaking comprehensive structural reforms, and the opportunities created by Asia’s rapid growth. Nonetheless, further reforms in a variety of areas will be required. In this regard, Directors noted the findings of the Competition Policy Review and looked forward to their implementation. Furthermore, addressing infrastructure needs will relieve bottlenecks and housing supply constraints. Directors also encouraged a shift toward more efficient taxes, while ensuring fairness.

Directors supported the recommendations of the Financial System Inquiry. They noted that while banks are sound and profitable, significantly higher capital would be needed in a severe adverse scenario to ensure a fully-functioning system. Accordingly, they welcomed the authorities’ commitment to make banks’ capital “unquestionably strong” over time. To address risks in the housing market, Directors supported targeted action by the regulator. They cautioned that if investor lending and house price inflation do not slow appreciably, these policies may need to be intensified.