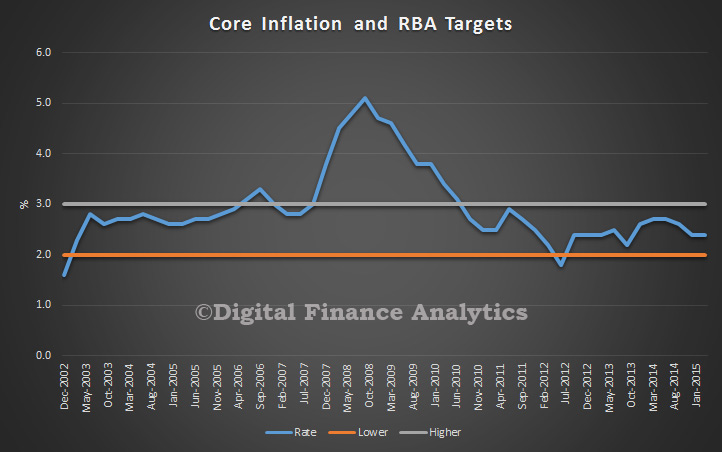

A timely and interesting speech today from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand by John McDermott, Assistant Governor & Chief Economist, “The Dragon Slain?” on the subject of inflation, why its low, and the limits of monetary policy on managing it. Like Australia, there is a significant imbalance between non-tradables and tradables and from an international perspective its a global phenomenon, with inflation in 16 out of 18 countries examined below target.

Introduction

It is a pleasure for me to be here today to address the Chamber. As some of you may be aware, today is St George’s Day, the saint famous for slaying a dragon. The subject of my speech is inflation, which has in the past been likened to a dragon ravaging society. With annual inflation in the March quarter at 0.1 percent, is this another slain dragon? I do not believe so; the dragon is merely sleeping.

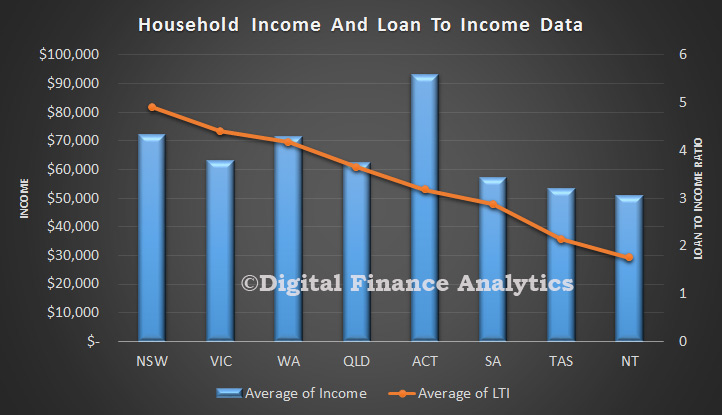

Inflation is currently low, and is mostly due to negative tradables inflation caused by the slow global economic recovery, the high exchange rate, and the recent sharp falls in oil prices (figure 1). There is little monetary policy can to do influence inflation outturns in the near term. Our strategy for returning inflation to the midpoint of the target range is to maintain stimulatory monetary policy to help generate output growth in excess of potential growth for an extended period.[1] This strength in aggregate demand relative to supply will help generate the inflation required to reach the midpoint objective.

Figure 1: Annual CPI headline, tradables and non-tradables inflation

Source: Statistics New Zealand.

With the benefit of hindsight, the low inflation outturn can be explained. Tradables inflation has been negative for the past three years as a result of: the slow global recovery; weak or declining prices of capital goods manufactured products and commodities; and the strength of our exchange rate. In the three years to March 2015 the cost of new cars fell 9 percent, major household appliances 9 percent, computing equipment by 32 percent; televisions and other audio-visual equipment prices fell by 36 percent.

More recently, a sharp decline in the oil price has driven tradables inflation down even further. The fall in petrol prices alone reduced the headline inflation rate in the March quarter by 0.8 percentage points. In the face of falling oil prices, the Bank’s focus is on the medium-term trend in inflation since this is the horizon at which monetary policy can best affect inflation. The Bank is unable to offset large relative price shocks and any attempt to do so by sharply reducing interest rates would result in an unnecessary boom then slowdown in activity. Unnecessary volatility in output and interest rates that our Policy Targets Agreement directs us to avoid.

In my remarks today, I am not going to focus on the inflation numbers we received earlier this week. We will consider those, along with all the other indicators of capacity and inflationary pressures, next week in our April OCR meeting. Instead, I will offer some perspective on low inflation in New Zealand over the past couple of years. In particular, I will outline the framework we use to think about inflationary pressures in New Zealand, then consider how the global economy is affecting New Zealand inflation. I then discuss some factors that might be contributing to somewhat weaker-than-expected domestic inflationary pressures.

Inflation and its causes

At the horizon relevant for monetary policy, inflation is typically thought of as being influenced by two main factors: capacity pressure and inflation expectations. The changing balance between aggregate demand and aggregate supply over the business cycle causes inflation to rise and fall. While the long run path of output is determined by the supply side of the economy – labour supply, investment and technology[2] – over the business cycle output can be above this ‘potential’ level (a positive output gap) or below it (a negative output gap) for several years. Periods of strong demand see inflation rise, while downswings see inflation fall. The other main influence on inflation is expectations of future inflation, which people build into price and wage setting.

Economists often summarise the implications for inflation of the output gap and inflation expectations in a ‘Phillips curve’. This relationship indicates that over periods of several years inflation tends to be higher when demand is stronger; and that over the cycle and in the long run inflation will be higher when inflation expectations are higher.

The Reserve Bank pursues its inflation target by setting the Official Cash Rate (OCR). Higher interest rates tend to lower inflation over the following 18 to 24 months by slowing the growth in aggregate demand, and reducing the output gap. In the short term, movements in interest rates can also cause the exchange rate to move, affecting the New Zealand dollar prices of imports. The long lag involved from changes to the OCR having their full effect on inflation requires the Reserve Bank to react to expected future inflationary pressure rather than past outturns.[3]

International factors

The sharp decline in global oil prices over the past year has had a large impact on headline inflation. The Dubai price for crude oil is now 44 percent below its June 2014 peak. This lower oil price affects domestic prices through several channels.[4] It directly affects the price of petrol paid by consumers; petrol prices are 15 percent lower than a year ago, reducing headline CPI inflation by 0.8 percentage points. If petrol prices remain unchanged over the coming year, this reduction will unwind, boosting annual inflation by 0.8 percentage points.

Falling oil prices indirectly affect consumer prices by reducing the production costs of other businesses. How much, depends on the share of oil and petrol in total costs, businesses’ expectations of how permanent the fall will be, and how businesses change their prices in relation to changes in costs. Our research on price-setting behaviour suggests that New Zealand businesses are more likely to pass on to customers an increase in costs than a decrease.[5]

The significance of this sharp decline in oil prices for inflation depends on whether the fall is caused by factors specific to the oil market, or is symptomatic of a more general fall in global economic activity. The Bank’s view is that this drop in oil prices is caused by a mix of factors, but primarily increased supply.

When declining oil prices reflect factors specific to the oil sector, it should be viewed as a relative price shift, rather than generalised inflation. It is a positive supply shock for New Zealand: it lowers inflation and boosts output. Since monetary policy operates with a lag, it cannot react to the immediate impact of oil prices on inflation. Any such response would affect output and inflation after the initial impact on petrol prices has left the annual inflation rate. The Policy Targets Agreement directs the Reserve Bank to avoid unnecessary volatility in output and interest rates and instead focus on medium-term inflationary pressure.

Inflation is low globally (figure 2), and below target in 16 out of 18 inflation targeting countries.[6] The low inflation reflects falling oil prices and the prolonged period of excess capacity in most advanced economies. But even accounting for oil and weak capacity pressures, inflation is weak in our trading partners, and lower than policymakers had forecast.[7] Weak inflation and continued excess capacity have resulted in extraordinarily supportive monetary policy across the world.

Figure 2: World inflation 2008 Q3 and 2014 Q4

Source: IMF, ILO, Eurostat, Haver Analytics, Thomson Reuters Datastream and various national sources.

Global inflation affects inflation in New Zealand via two main channels.[8] Low inflation in our trading partner economies results in small international price increases for New Zealand’s imports. Extremely low, and in some cases negative, interest rates overseas have been a factor causing an appreciation of the New Zealand dollar, which further depresses import prices when expressed in New Zealand dollar terms.

The pass-through of global inflation to New Zealand import prices seems to be taking place in a normal way (figure 3). Similarly, tradable CPI inflation appears consistent with the movements in import prices. Nonetheless, the combination of surprisingly weak inflation overseas and our high exchange rate are the principal reasons why we have had downside surprises to headline inflation.

Figure 3: Trading partner export prices and New Zealand import prices (US dollar terms)[9]

Source: Haver Analytics, Statistics New Zealand and RBNZ estimates.

While the weakness in tradables inflation is explainable given international factors, non-tradables inflation has also been weaker than expected. In part the weakness in non-tradables may be influenced by international factors, since around a tenth of non-tradable prices are accounted for by imports.[10] Indeed, looking more closely at non-tradables, the sectors that are relatively more open to international competition exhibit lower inflation at present.[11]

Domestic inflationary pressures

While non-tradables account for a small part of the overall weakness in headline inflation, the dynamics of non-tradables inflation is central to our strategy of returning inflation to the target midpoint. In this context I will discuss our estimates of spare capacity in the economy, how that spare capacity affects price and wage-setting behaviour, and the inflation expectations of wage and price setters. None of these areas are directly observable, and require estimation by economic models based on available indicators.

Spare capacity in New Zealand

Estimates of the output gap are difficult to carry out in real time, and can be heavily revised. To mitigate this uncertainty, we corroborate our estimates of the output gap from our main model with a range of other indicators of capacity pressures. These measures suggest that the output gap was negative for much of the past couple of years, explaining why non-tradables inflation has been weak. The indicators point to the current output gap being positive, at around half a percent of potential output (figure 4). Monetary policy is currently supportive, which should help to drive the output gap higher in coming quarters and generate the additional inflation to return to the target midpoint.

Figure 4: Output gap and indicator suite (percent of potential output)

Source: RBNZ estimates.

The weakest indicators, though, are consistent with a negative output gap, and hence lower inflationary pressure. The weakest one at present is based on the unemployment rate, which could be influenced by immigration and structural changes in participation. Net immigration is running at historically high levels, and has two offsetting effects on inflationary pressure. Immigrants require housing and new capital equipment to work, increasing aggregate demand. At the same time, immigrants may increase the labour force, increasing supply in the economy and reducing wage inflation. These offsetting forces make it hard to calibrate the net effect of migrants on the output gap in the short run.[12]

Labour force participation in New Zealand is currently at record levels, due to the upward trend in participation of female workers and higher participation among older cohorts. Should that high rate of participation prove permanent it would imply a greater level of potential output than we currently estimate, a smaller positive output gap and lower non-tradable inflation.

The impact of capacity pressure on inflation

All of the various indicators of capacity pressures have one thing in common. Each indicator shows a gradual tightening of capacity pressure over the past couple of years, which should be consistent with gradually increasing inflationary pressures and higher inflation outcomes. The subdued nature of the actual increase in domestic inflationary pressure raises the question of whether the output gap is having a smaller influence on actual inflation than it has in the past. In other words, has the slope of the Phillips curve become flatter?

Consider a stylised version of the New Zealand Phillips curve, mapping the outturns for inflation and a simple output gap measure – the deviation of unemployment from trend (figure 5).[13] During the 1970s, there were large movements in inflation without much corresponding movement in the unemployment gap. In part this may be a function of labour hoarding by businesses as the general shortage of labour made them reluctant to lay off workers even faced with large swings in output.

Figure 5: New Zealand Phillips curves

Source: Statistics New Zealand, RBNZ estimates.

During the 1980s, there is a clear negative relationship, with higher unemployment gaps associated with lower outcomes for inflation. Since the introduction of inflation targeting in 1990, the curve is markedly flatter – large movements in the unemployment gap have not resulted in corresponding changes in inflation. The flattening of the Phillips curve is witnessed in many countries. Nonetheless, experience since the global financial crisis has led many policymakers to question whether it has flattened further in recent years.[14] During the depths of the global financial crisis, non-tradables inflation remained stubbornly high, in New Zealand and elsewhere, despite large negative output gaps.

This anchoring of inflation at low levels represents a success for the monetary policy framework, as shocks hitting New Zealand do not result in big changes to general price inflation. But it also poses a challenge. With a flat Phillips curve it becomes more difficult for the Reserve Bank to influence inflation by affecting the demand for resources and the size of the output gap. The current flatter Phillips curve could mean that the positive output gap is exerting less inflationary pressure than we currently believe, slowing our eventual return to target midpoint.

Has pricing behaviour changed?

Survey measures of inflation expectations have fallen in recent quarters. The decline in expectations is consistent with the decline in actual inflation over the period. In the decade to 2012, CPI inflation averaged 2.6 percent and was in the upper half of the Reserve Bank’s target range. The current Policy Targets Agreement (signed in 2012) put greater focus on achieving the midpoint of the target range, so some decline in inflation expectations should be expected. Lower inflation expectations have been observed across the globe.[15]

What matters for inflation is not the average response to a particular survey of expectations, but how general inflation expectations held by businesses and households translate into price-setting behaviour and wage bargaining. Research on price-setting by New Zealand businesses suggest that many only take into account current inflation when setting prices, and very few businesses are purely forward looking.[16] Preliminary work on wage setting in New Zealand also points to the importance of past inflation outturns.[17]

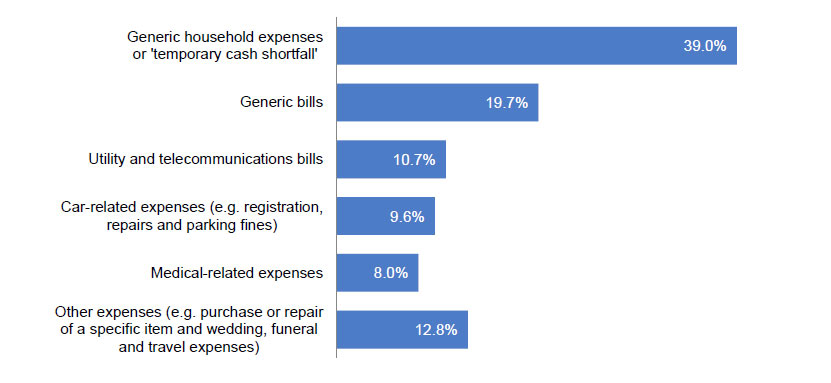

The evolution of inflation expectations over coming quarters merits vigilance. If price and wage setting is very backward looking, the temporarily low headline inflation from falling petrol prices could become more widely entrenched.[18] There is certainly a growing discussion of low inflation captured in the media (figure 6). Recent research has pointed to possible asymmetries in behaviour, with inflation expectations becoming more backward looking in periods of low inflation, and reacting more to downside inflation surprises than upside ones.[19] A certain degree of movement in expectations is to be expected, particularly for short-term measures, but the more firmly anchored expectations are, the smaller the overall inflation impact.[20]

Figure 6: Media articles in New Zealand citing ‘low inflation’

Source: Fuseworks, Statistics New Zealand.

Longer-term survey measures of inflation expectations are currently consistent with the midpoint of our target (figure 7). Estimates from a range of economic models are somewhat lower and have declined recently. A market-based measure using the return on an inflation-indexed bond has also fallen sharply over the past year.[21] The level of these other measures are consistent with inflation expectations at or just below the target midpoint of 2 percent, but all highlight the downward direction over the past year (table 1).[22]

Figure 7: Long-term inflation expectations

Source: Aon, Statistics New Zealand, RBNZ/UMR.

Table 1: Summary of inflation expectation measures

|

Current estimate |

Range for current estimate |

Direction of change in last year |

Consistent with midpoint |

| Survey measures* |

2.1 |

1.8 – 2.2 |

↓ |

|

| Model-based measures |

1.4 |

1 – 1.5 |

↓ |

|

| Market based measure |

1.5 |

1.5 |

↓ |

|

| *Excluding surveys of less than 1-year ahead |

|

|

The outlook for monetary policy

I have talked today about the causes of recent low inflation in New Zealand. The outlook for inflation is also subdued, and suggests that monetary policy should remain stimulatory for a prolonged period. This cycle is unusual in that CPI inflation is staying very low, requiring interest rates to also remain low. The timing of future adjustments in interest rates will depend on the evolution of inflationary pressures in both the traded and non-traded sectors. We continue to monitor and carefully assess the emerging flow of economic data.

The impact of some factors influencing headline inflation will prove temporary. Past declines in oil prices will reduce headline inflation substantially in 2015, but absent any further falls this negative contribution will drop out of the annual inflation rate by the start of next year.

Looking ahead, we will ensure that monetary policy is stimulatory to support output growth above potential. Increasingly, this positive output gap will help lift non-tradables inflation, returning headline inflation gradually to the target midpoint. Real GDP growth has been above potential growth for a number of years and is currently underpinned by high net immigration, strong construction activity and robust household spending. Employment growth is strong and the unemployment rate is low and projected to fall.

At present, the Bank is not considering any increase in interest rates. Before considering any tightening in monetary policy we would need to be confident that increased capacity utilisation and labour market tightness was generating, or about to generate, a substantial increase in inflation.

Evidence of weakening demand and domestic inflationary pressures would prompt us to consider lowering interest rates. There are some areas of uncertainty surrounding the outlook for capacity pressures, including the lingering effects of the recent drought in parts of the country, fiscal consolidation, lower dairy incomes and the impact of the high exchange rate on some export and import substitution industries. Beyond these factors, we are also assessing the outlook for tradables inflation that is being dampened by global conditions and the high exchange rate. The fact that the exchange rate has appreciated while our key export prices, such as dairy, have been falling, is unwelcome.

We remain vigilant in watching wage bargaining and price-setting outcomes. Should these settle at levels lower than our target range for inflation, it would be appropriate to ease policy.

Concluding comments

Inflation has been low in New Zealand for a number of years. At present, the outlook requires a period of supportive monetary policy. Our approach, as a flexible inflation targeter, is to support ongoing sustainable growth in New Zealand that should help raise costs and prices in order to achieve our inflation target. We will not react to temporary deviations from target, as this will only generate unnecessary volatility in activity.

[1] In setting monetary policy, we have to consider whether we have calibrated the degree of monetary stimulus correctly. In our framework we measure the degree of monetary policy stimulus by the gap between actual interest rates and the so-called neutral interest rate. Our current estimate is for a neutral 90-day rate of 4.5 percent. We lowered our estimate of the neutral rate following the global financial crisis to reflect the higher debt levels of households and higher financing costs pushing up the spread between the 90-day rate and the interest rate on household mortgages. See McDermott, J (2013), ‘Shifting gear: why have neutral interest rates fallen’, Assistant Governor, RBNZ. Speech to New Zealand Institute of Chartered Accountants CFO and Financial Controllers Special Interest Group in Auckland, 2 October; and Chetwin, W and A Wood (2013), ‘Neutral interest rates in the post-crisis world’, RBNZ Analytical Note, No. 2013/07.

[2] For a detailed description of our modelling framework for potential output, see: McDermott, J (2014), ‘Realising our potential: potential output and the monetary policy framework’, Assistant Governor, RBNZ. Speech to the Wellington Chamber of Commerce, 9 July and Lienert, A and D Gillmore (2015), ‘The Reserve Bank’s method of estimating “potential output’, RBNZ Analytical Note, 2015/01.

[3] This is a broad, high-level summary of our framework. In carrying out a monetary policy review we take into consideration a wide range of factors, which I do not have time to detail today. In these remarks I am focusing on the key issues around the dynamics of inflation.

[4] See Chapter 6 of the March 2015 Monetary Policy Statement for a fuller description of the impact of oil prices on consumer prices.

[5] Parker, M (2014c), ‘Price-setting behaviour in New Zealand’, RBNZ Discussion Paper, No. 2014/04.

[6] Carney, M (2015), ‘Writing the path back to target’, Governor, Bank of England. Speech at the University of Sheffield Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre, 12 March.

[7] E.g. Bank of Canada (2014), ‘Box 2: Assessing the impact of excess supply on inflation’, Monetary Policy Report, April. Carney, M (2015) ibid., Haldane, A (2015), ‘Drag and drop’, Chief Economist, Bank of England. Speech at the Bizclub lunch, Rutland, 19 March. Sveriges Riksbank (2014), ‘Why is inflation low?’, Monetary Policy Report, July.

[8] For a more detailed description of how the international situation passes through to New Zealand consumer prices, see Parker, M (2014a), ‘Exchange-rate movements and consumer prices: some perspectives’, RBNZ Bulletin, 77 (1, March): 31-41.

[9] The series for China has a shorter history, but adding it does not qualitatively affect the path for trading partner export prices.

[10] Parker, M (2014b), ‘How much of what New Zealanders consume is imported? Estimates from input-output tables’, RBNZ Analytical Note, No. 2014/05.

[11] See Galt, M (2015), ‘How do international factors affect non-tradable inflation? Exploratory analysis using disaggregated trans-Tasman data’, RBNZ Analytical Note. Forthcoming. Nonetheless, even accounting for global inflation factors, inflation in New Zealand appears weak, see Richardson, A (2015), ‘The pass-through of global economic conditions to New Zealand inflation’, RBNZ Analytical Note. No. 2015/03.

[12] Our own research suggests that different types of immigrants to New Zealand have differing implications for overall inflationary pressure. See McDonald, C (2013), ‘Migration and the housing market’, RBNZ Analytical Note, No. 2013/10.

[13] The unemployment gap is calculated at the percentage point deviation of the actual unemployment rate from a trend calculated using a stiff Hodrick-Prescott filter (lambda = 50000). A positive unemployment gap represents slack in the labour marker, so would be equivalent to a negative output gap.

[14] See Yellen, J (2014) ‘Labor market dynamics and monetary policy’, Chair, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Speech given at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Symposium, Jackson Hole. Haldane, A (2015), op.cit. The IMF estimates that the slope of the global price Phillips curve has fallen from around 1 in the 1970s to 0.1-0.2 most recently. See IMF (2013), ‘The dog that didn’t bark: Has inflation been muzzled or was it just sleeping?’, World Economic

Outlook, April 2013.

[15] For example, see Nechio, F (2015), ‘Have long-term inflation expectations declined?’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, No. 2015-11; Haldane, A (2015) op cit.; Miccoli, M and S Neri (2015) ‘Inflation surprises and inflation expectations in the euro area’, Banca d’Italia Occasional Papers, No. 265.

[16] Parker, M (2014c), op. cit.

[17] Armstrong, J and M Parker (2015) ‘How wages are set: evidence from a large survey of firms’, Reserve Bank of New Zealand. Forthcoming.

[18] Our research suggests that when supply shocks are permanent in nature, monetary policy will need to focus more on inflation outturns and less on the output gap than is the case when supply shocks are temporary. The intuition behind this result is that with supply shocks having permanent effects, inflation expectations will eventually become unanchored unless the central bank acts to keep inflation stationary around target. See Yao, F (2014), ‘Stabilising Taylor rules when the supply shock has a unit root’, Journal of Macroeconomics. Forthcoming.

[19] Ehrmann, M (2014), ‘Targeting inflation from below – how do inflation expectations behave?’, Bank of Canada Working Paper, No. 2014-52. The impact of downside surprises in inflation outturns on expectations has been observed recently in the euro area, see Miccoli, M and S Neri (2015) op. cit.

[20] Wong, B (2014), ‘Inflation expectations and how it explains the inflationary impact of oil price shocks: evidence from the Michigan survey’, CAMA Working Paper, No. 45/2014. demonstrates these facts for the United States following oil price shocks using the Michigan survey of household inflation expectations.

[21] Limited liquidity in this bond, and the lack of a long history suggests caution should be taken over the reliability of this measure, but the direction of change is indicative of lower inflation expectations.

[22] Lewis, M (2015), ‘Measuring inflation expectations’, RBNZ Analytical Note. Forthcoming.