In the UK interest rates are artificially low, and in Australia, rates were cut last month. What are the potential implications of a low interest rate policy? Is it good strategy, or a gamble?

In a speech given by Kristin Forbes, External MPC Member, Bank of England, the various impacts of ultra-low interest rates are outlined. It is worth reflecting on the significant range of implications.

By way of background, the UK, recovery is now well in progress and self-sustaining – despite continual headwinds from abroad, unemployment has fallen rapidly, from 8.4% about 3 years ago to 5.7% today, and is expected to continue to fall to reach its equilibrium rate within two years. Wage growth appears to finally be picking up, so that when combined with lower oil prices, families will, at long last, see their real earnings increase. However, one piece of the economy that has not yet started this process of normalization, however, is interest rates. Bank Rate – the main interest rate set by the Bank of England – remains at its emergency level of 0.5%. This near-zero interest rate made sense during the crisis and early stages of the faltering recovery. It continues to make sense today. But at what point will it no longer make sense? Low interest rates provide a number of benefits. For example, they make it easier for individuals, companies and governments to pay down debt. They make it more attractive for businesses to invest – stimulating production and job creation. They have helped allow the financial system to heal. They have played a key role in supporting the UK’s recent recovery. Increases in interest rates – especially after being sustained at low levels for so long – can also involve risks.

But there are also costs and risks from keeping interest rates at emergency levels for a sustained period, especially as an economy returns to more normal functioning. Interest rates sustained at emergency levels could lead to significant issues. We summarise the main arguments.

(1) inflationary pressures

Low headline inflation and stable domestically-generated inflation are unlikely to persist if interest rates remain low. The output gap is closing and there is limited slack left in the economy. The rate of wage growth is increasing – with AWE total pay growth in the three months to December of 2.1% relative to a year earlier, but 5.4% (annualised) relative to 3-months earlier. Since wages are an important component of prices and their recent pick-up has not been matched with a corresponding increase in productivity, these wage increases will support a pickup in inflation. If this pickup is gradual, as expected, inflationary pressures should only build slowly over time, so that interest rates can be increased slowly and gradually as necessary.

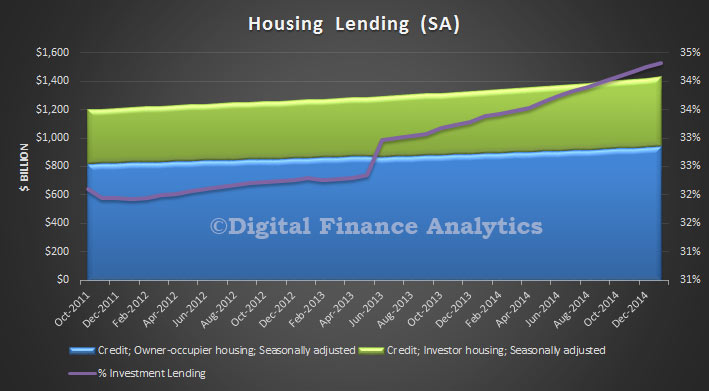

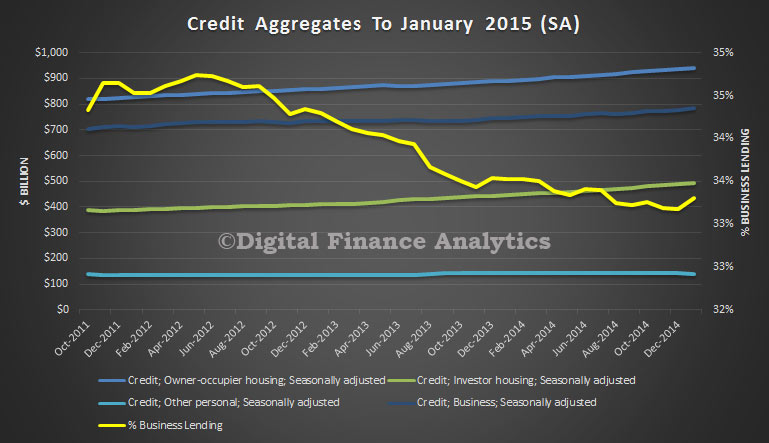

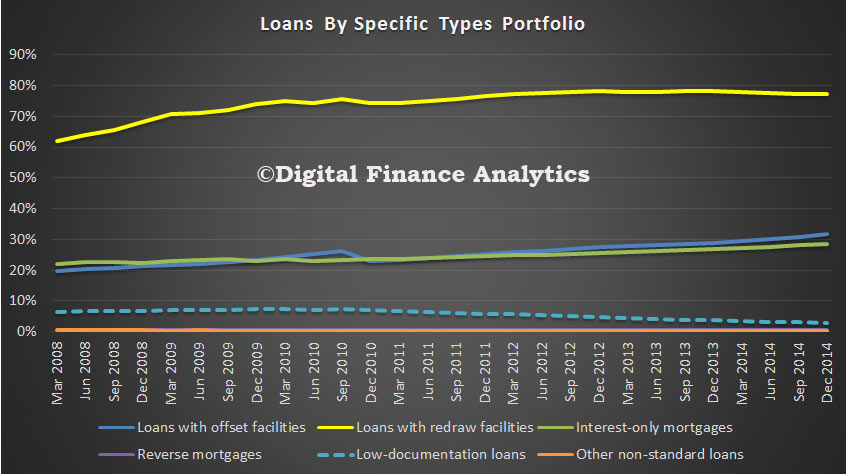

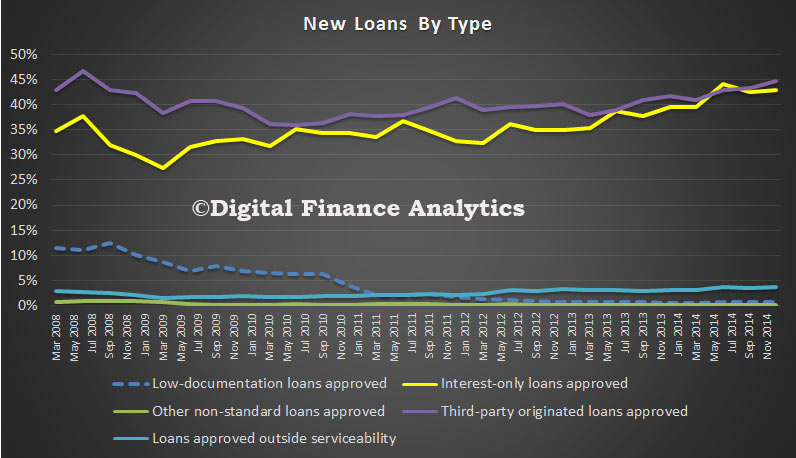

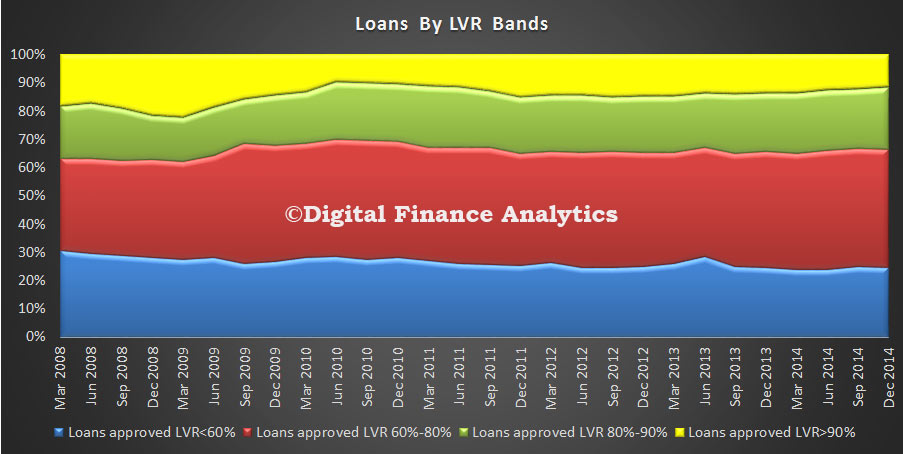

(2) asset bubbles and financial vulnerabilities

As rates continue to be low, especially during a period of recovery, the risks to the financial system could grow. More specifically, when interest rates are low, investors may “search for yield” and shift funds to riskier investments that are expected to earn a higher return – from equity markets to high-yield debt markets to emerging markets. This could drive up prices in these other markets and potentially create “bubbles”. This can not only lead to an inefficient allocation of capital, but leave certain investors with more risk than they appreciate. An adjustment in asset prices can bring about losses that are difficult to manage, especially if investments were supported by higher leverage possible due to low rates. If these losses were widespread across an economy, or affected systemically-important institutions, they could create substantial economic disruption.

(3) limited tools to respond to future challenges

There is less “firepower” to respond to future contingencies. There is no shortage of events that could cause growth to slow and inflation to fall in the future – and the first response is normally to reduce interest rates. Reductions in interest rates can be an important tool for stabilizing an economy. If Bank Rate remains around its current level of 0.5%, however, there is obviously not room during the next recession to lower it to the degree that has typically occurred. Bank Rate could go a bit lower than 0.5%. But rates could not be lowered by the average 3.8 percentage points that occurred during past easing cycles without creating severe distortions to the financial system and functioning of the economy. Regulators could instead use other tools to loosen monetary policy – such as guidance on future rate changes or quantitative easing. These tools are certainly viable, but it is harder to predict their impact and harder to assess their effectiveness than for changes in interest rates.

(4) an inefficient allocation of resources and lower productivity

Is there a chance that a prolonged period of near-zero interest rates is allowing less efficient companies to survive and curtailing the “creative destruction” that is critical to support productivity growth? Or even within existing, profitable companies – could a prolonged period of low borrowing costs reduce their incentive to carefully assess and evaluate investment projects – leading to a less efficient allocation of capital within companies? Any of these effects of near zero-interest rates could play a role in explaining the UK’s unusually weak productivity growth since the crisis. These types of concerns gained attention in Japan during the 1990s after the collapse of the Japanese real estate and stock market bubbles. During this period, many banks followed a policy of “forbearance”, during which they continued to lend to companies that would otherwise have been insolvent. These unprofitable companies kept alive by lenient banks were often referred to by the colourful name of “zombies”.

(5) vulnerabilities in the structure of demand

A fifth possible cost of low interest rates is that it could shift the sources of demand in ways which make underlying growth less balanced, less resilient, and less sustainable. This could occur through increases in consumption and debt, and decreases in savings and possibly the current account. Some of these effects of low interest rates on the sources of demand are not surprising and are important channels by which low interest rates are expected to stimulate growth. But if these shifts are too large – or vulnerabilities related to over consumption, over borrowing, insufficient savings, or large current account deficits continue for too long – they could create economic challenges.

(6) higher inequality

A final concern related to an extended period of ultra-accommodative monetary policy is how it might affect inequality. Changes in monetary policy always have distributional implications, but these concerns have recently received renewed attention – possible due to increased concerns about inequality more generally, or possibly because quantitative easing has more immediate and apparent distributional implications. How a sustained period of low interest rates impacts inequality, however, is far from clear cut. There are some channels by which low interest rates – and especially quantitative easing – can aggravate inequality. As discussed above, lower interest rates tend to boost asset values. Recent episodes of quantitative easing have also appeared to increase asset prices – especially in equity markets – although the magnitude of this effect is hard to estimate precisely. Holdings of financial assets are heavily skewed by age and income group, with close to 80% of gross financial assets of the household sector held by those over 45 years old and 40% held by the top 5% of households. As discussed in a recent BoE report, these older and higher income groups will therefore see a bigger boost to their financial savings as a result of low interest rates and quantitative easing. But, counteracting these effects, are also powerful channels by which lower interest rates (and quantitative easing) can reduce inequality and disproportionately harm older income groups. More specifically, one powerful effect of low rates is to reduce pension annuity rates, interest on savings, and other fixed-income payments. This disproportionately affects the older population (who relies on pensions and fixed income as a larger share of their income) and people in the middle of the income distribution (who have some savings, but less exposure to more sophisticated investments that can increase in value from lower rates). In addition to affecting the asset and earnings side of individual’s balance sheets, there can also be distributional consequences on the liability and payment side. As interest rates and the cost of servicing debt fall, individuals with mortgages and other borrowing can benefit. These benefits tend to disproportionately fall on the middle class – for which mortgage and debt payments are a higher share of total income – but can also benefit the wealthy if they have high levels of borrowing.

The full PowerPoint presentation is available here.